December 2012 Number 1 - Utah Native Plant Society

December 2012 Number 1 - Utah Native Plant Society

December 2012 Number 1 - Utah Native Plant Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Utah</strong> <strong>Native</strong> <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

“escape route” (Grabherr et al. 1995; Halloy and Mark<br />

2003). Perhaps this can be attributed to unusual features<br />

of plant endemism in the western United States in general<br />

and, more specifically, in the Intermountain West.<br />

Kruckeberg (1986) reformulated earlier works characterizing<br />

the processes of soil formation and vegetation<br />

development (Jenny 1941; Major 1951) to account for<br />

plant diversity in any region. He noted that topography,<br />

parent material, and the timing of geological processes<br />

or events created a patchiness or discontinuity of edaphic<br />

phenomena that creates additional opportunity for<br />

biological discontinuity. i.e., speciation. He termed endemic<br />

taxa that result from this process “geoedaphics”<br />

(Kruckeberg 1986). Rajakaruna (2004) provided a<br />

review that emphasized the role that unusual soil conditions<br />

play in the diversification of plant species.<br />

Although Kruckeberg (1986) emphasized the role of<br />

bedrock (and especially serpentine) outcrops in the evolution<br />

of geoedaphics, in an earlier paper Kruckeberg<br />

and Rabinowitz (1985), cast a broader net with respect<br />

to narrowly distributed endemics (sensu Mason<br />

1946a,b), noting that unique taxa associated with<br />

“gypsum, serpentine, limestone, alkaline and heavy<br />

metal soils are well known to field botanists in many<br />

parts of the world.” While few, if any, serpentine outcrops<br />

are known from the Great Basin in Nevada, the<br />

Calcareous Mountains Section of the Intermountain region,<br />

which lies primarily in the eastern half of Nevada<br />

and adjacent southwestern <strong>Utah</strong>, is recognized as the<br />

richest area of the Great Basin for plant endemism<br />

(Holmgren1972a). Elsewhere, examples of Great Basin<br />

plants restricted to exposures of carbonate bedrock are<br />

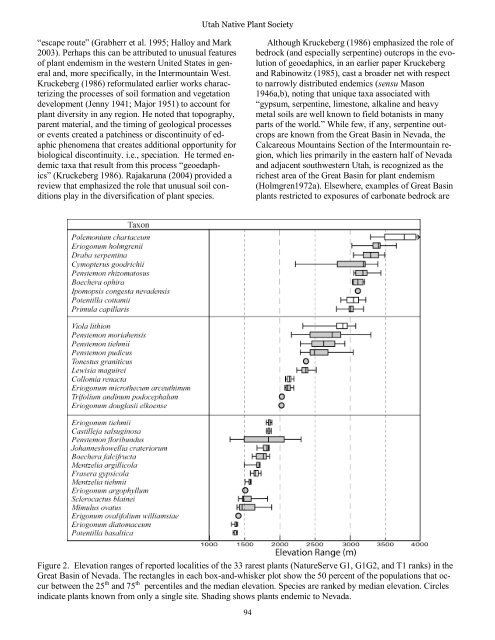

Figure 2. Elevation ranges of reported localities of the 33 rarest plants (NatureServe G1, G1G2, and T1 ranks) in the<br />

Great Basin of Nevada. The rectangles in each box-and-whisker plot show the 50 percent of the populations that occur<br />

between the 25 th and 75 th percentiles and the median elevation. Species are ranked by median elevation. Circles<br />

indicate plants known from only a single site. Shading shows plants endemic to Nevada.<br />

94