Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

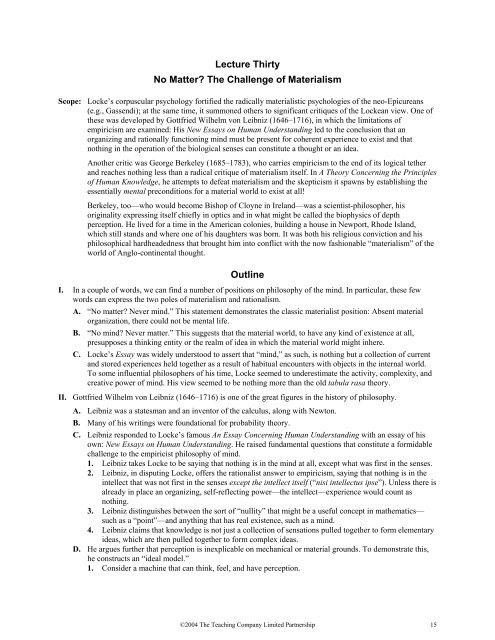

Lecture ThirtyNo Matter? The Challenge <strong>of</strong> MaterialismScope: Locke’s corpuscular psychology fortified the radically materialistic psychologies <strong>of</strong> the neo-Epicureans(e.g., Gassendi); at the same time, it summoned others to significant critiques <strong>of</strong> the Lockean view. One <strong>of</strong>these was developed by Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (1646–1716), in which the limitations <strong>of</strong>empiricism are examined: His New Essays on Human Understanding led to the conclusion that anorganizing and rationally functioning mind must be present for coherent experience to exist and thatnothing in the operation <strong>of</strong> the biological senses can constitute a thought or an idea.Another critic was George Berkeley (1685–1783), who carries empiricism to the end <strong>of</strong> its logical tetherand reaches nothing less than a radical critique <strong>of</strong> materialism itself. In A Theory Concerning the Principles<strong>of</strong> Human Knowledge, he attempts to defeat materialism and the skepticism it spawns by establishing theessentially mental preconditions for a material world to exist at all!Berkeley, too—who would become Bishop <strong>of</strong> Cloyne in Ireland—was a scientist-philosopher, hisoriginality expressing itself chiefly in optics and in what might be called the biophysics <strong>of</strong> depthperception. He lived for a time in the American colonies, building a house in Newport, Rhode Island,which still stands and where one <strong>of</strong> his daughters was born. It was both his religious conviction and hisphilosophical hardheadedness that brought him into conflict with the now fashionable “materialism” <strong>of</strong> theworld <strong>of</strong> Anglo-continental thought.OutlineI. In a couple <strong>of</strong> words, we can find a number <strong>of</strong> positions on philosophy <strong>of</strong> the mind. In particular, these fewwords can express the two poles <strong>of</strong> materialism and rationalism.A. “No matter? Never mind.” This statement demonstrates the classic materialist position: Absent materialorganization, there could not be mental life.B. “No mind? Never matter.” This suggests that the material world, to have any kind <strong>of</strong> existence at all,presupposes a thinking entity or the realm <strong>of</strong> idea in which the material world might inhere.C. Locke’s Essay was widely understood to assert that “mind,” as such, is nothing but a collection <strong>of</strong> currentand stored experiences held together as a result <strong>of</strong> habitual encounters with objects in the internal world.To some influential philosophers <strong>of</strong> his time, Locke seemed to underestimate the activity, complexity, andcreative power <strong>of</strong> mind. His view seemed to be nothing more than the old tabula rasa theory.II. Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (1646–1716) is one <strong>of</strong> the great figures in the history <strong>of</strong> philosophy.A. Leibniz was a statesman and an inventor <strong>of</strong> the calculus, along with Newton.B. Many <strong>of</strong> his writings were foundational for probability theory.C. Leibniz responded to Locke’s famous An Essay Concerning Human Understanding with an essay <strong>of</strong> hisown: New Essays on Human Understanding. He raised fundamental questions that constitute a formidablechallenge to the empiricist philosophy <strong>of</strong> mind.1. Leibniz takes Locke to be saying that nothing is in the mind at all, except what was first in the senses.2. Leibniz, in disputing Locke, <strong>of</strong>fers the rationalist answer to empiricism, saying that nothing is in theintellect that was not first in the senses except the intellect itself (“nisi intellectus ipse”). Unless there isalready in place an organizing, self-reflecting power—the intellect—experience would count asnothing.3. Leibniz distinguishes between the sort <strong>of</strong> “nullity” that might be a useful concept in mathematics—such as a “point”—and anything that has real existence, such as a mind.4. Leibniz claims that knowledge is not just a collection <strong>of</strong> sensations pulled together to form elementaryideas, which are then pulled together to form complex ideas.D. He argues further that perception is inexplicable on mechanical or material grounds. To demonstrate this,he constructs an “ideal model.”1. Consider a machine that can think, feel, and have perception.©2004 The Teaching Company Limited Partnership 15