Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

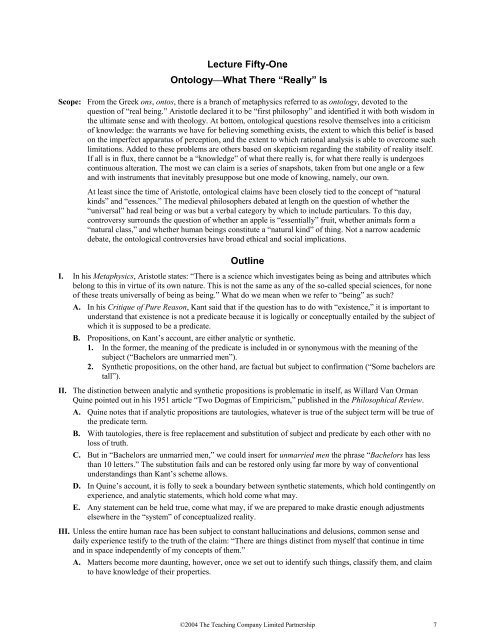

Lecture Fifty-OneOntology⎯What There “Really” IsScope: From the Greek ons, ontos, there is a branch <strong>of</strong> metaphysics referred to as ontology, devoted to thequestion <strong>of</strong> “real being.” Aristotle declared it to be “first philosophy” and identified it with both wisdom inthe ultimate sense and with theology. At bottom, ontological questions resolve themselves into a criticism<strong>of</strong> knowledge: the warrants we have for believing something exists, the extent to which this belief is basedon the imperfect apparatus <strong>of</strong> perception, and the extent to which rational analysis is able to overcome suchlimitations. Added to these problems are others based on skepticism regarding the stability <strong>of</strong> reality itself.If all is in flux, there cannot be a “knowledge” <strong>of</strong> what there really is, for what there really is undergoescontinuous alteration. The most we can claim is a series <strong>of</strong> snapshots, taken from but one angle or a fewand with instruments that inevitably presuppose but one mode <strong>of</strong> knowing, namely, our own.At least since the time <strong>of</strong> Aristotle, ontological claims have been closely tied to the concept <strong>of</strong> “naturalkinds” and “essences.” The medieval philosophers debated at length on the question <strong>of</strong> whether the“universal” had real being or was but a verbal category by which to include particulars. To this day,controversy surrounds the question <strong>of</strong> whether an apple is “essentially” fruit, whether animals form a“natural class,” and whether human beings constitute a “natural kind” <strong>of</strong> thing. Not a narrow academicdebate, the ontological controversies have broad ethical and social implications.OutlineI. In his Metaphysics, Aristotle states: “There is a science which investigates being as being and attributes whichbelong to this in virtue <strong>of</strong> its own nature. This is not the same as any <strong>of</strong> the so-called special sciences, for none<strong>of</strong> these treats universally <strong>of</strong> being as being.” What do we mean when we refer to “being” as such?A. In his Critique <strong>of</strong> Pure Reason, Kant said that if the question has to do with “existence,” it is important tounderstand that existence is not a predicate because it is logically or conceptually entailed by the subject <strong>of</strong>which it is supposed to be a predicate.B. Propositions, on Kant’s account, are either analytic or synthetic.1. In the former, the meaning <strong>of</strong> the predicate is included in or synonymous with the meaning <strong>of</strong> thesubject (“Bachelors are unmarried men”).2. Synthetic propositions, on the other hand, are factual but subject to confirmation (“Some bachelors aretall”).II. The distinction between analytic and synthetic propositions is problematic in itself, as Willard Van OrmanQuine pointed out in his 1951 article “Two Dogmas <strong>of</strong> Empiricism,” published in the Philosophical Review.A. Quine notes that if analytic propositions are tautologies, whatever is true <strong>of</strong> the subject term will be true <strong>of</strong>the predicate term.B. With tautologies, there is free replacement and substitution <strong>of</strong> subject and predicate by each other with noloss <strong>of</strong> truth.C. But in “Bachelors are unmarried men,” we could insert for unmarried men the phrase “Bachelors has lessthan 10 letters.” The substitution fails and can be restored only using far more by way <strong>of</strong> conventionalunderstandings than Kant’s scheme allows.D. In Quine’s account, it is folly to seek a boundary between synthetic statements, which hold contingently onexperience, and analytic statements, which hold come what may.E. Any statement can be held true, come what may, if we are prepared to make drastic enough adjustmentselsewhere in the “system” <strong>of</strong> conceptualized reality.III. Unless the entire human race has been subject to constant hallucinations and delusions, common sense anddaily experience testify to the truth <strong>of</strong> the claim: “There are things distinct from myself that continue in timeand in space independently <strong>of</strong> my concepts <strong>of</strong> them.”A. Matters become more daunting, however, once we set out to identify such things, classify them, and claimto have knowledge <strong>of</strong> their properties.©2004 The Teaching Company Limited Partnership 7