Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

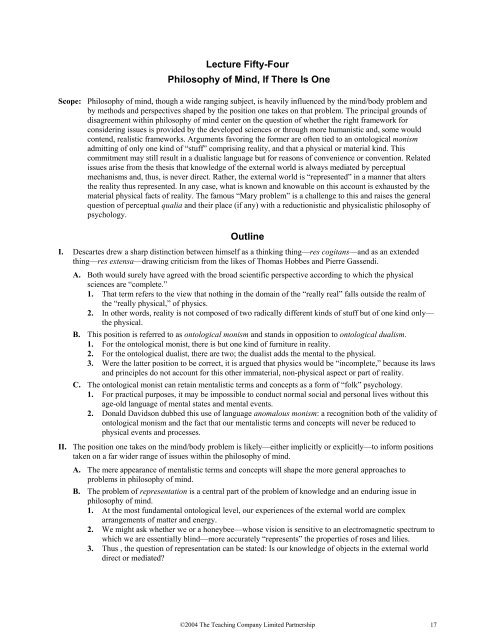

Lecture Fifty-Four<strong>Philosophy</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mind, If There Is OneScope: <strong>Philosophy</strong> <strong>of</strong> mind, though a wide ranging subject, is heavily influenced by the mind/body problem andby methods and perspectives shaped by the position one takes on that problem. The principal grounds <strong>of</strong>disagreement within philosophy <strong>of</strong> mind center on the question <strong>of</strong> whether the right framework forconsidering issues is provided by the developed sciences or through more humanistic and, some wouldcontend, realistic frameworks. Arguments favoring the former are <strong>of</strong>ten tied to an ontological monismadmitting <strong>of</strong> only one kind <strong>of</strong> “stuff” comprising reality, and that a physical or material kind. Thiscommitment may still result in a dualistic language but for reasons <strong>of</strong> convenience or convention. Relatedissues arise from the thesis that knowledge <strong>of</strong> the external world is always mediated by perceptualmechanisms and, thus, is never direct. Rather, the external world is “represented” in a manner that altersthe reality thus represented. In any case, what is known and knowable on this account is exhausted by thematerial physical facts <strong>of</strong> reality. The famous “Mary problem” is a challenge to this and raises the generalquestion <strong>of</strong> perceptual qualia and their place (if any) with a reductionistic and physicalistic philosophy <strong>of</strong>psychology.OutlineI. Descartes drew a sharp distinction between himself as a thinking thing—res cogitans—and as an extendedthing—res extensa—drawing criticism from the likes <strong>of</strong> Thomas Hobbes and Pierre Gassendi.A. Both would surely have agreed with the broad scientific perspective according to which the physicalsciences are “complete.”1. That term refers to the view that nothing in the domain <strong>of</strong> the “really real” falls outside the realm <strong>of</strong>the “really physical,” <strong>of</strong> physics.2. In other words, reality is not composed <strong>of</strong> two radically different kinds <strong>of</strong> stuff but <strong>of</strong> one kind only—the physical.B. This position is referred to as ontological monism and stands in opposition to ontological dualism.1. For the ontological monist, there is but one kind <strong>of</strong> furniture in reality.2. For the ontological dualist, there are two; the dualist adds the mental to the physical.3. Were the latter position to be correct, it is argued that physics would be “incomplete,” because its lawsand principles do not account for this other immaterial, non-physical aspect or part <strong>of</strong> reality.C. The ontological monist can retain mentalistic terms and concepts as a form <strong>of</strong> “folk” psychology.1. For practical purposes, it may be impossible to conduct normal social and personal lives without thisage-old language <strong>of</strong> mental states and mental events.2. Donald Davidson dubbed this use <strong>of</strong> language anomalous monism: a recognition both <strong>of</strong> the validity <strong>of</strong>ontological monism and the fact that our mentalistic terms and concepts will never be reduced tophysical events and processes.II. The position one takes on the mind/body problem is likely—either implicitly or explicitly—to inform positionstaken on a far wider range <strong>of</strong> issues within the philosophy <strong>of</strong> mind.A. The mere appearance <strong>of</strong> mentalistic terms and concepts will shape the more general approaches toproblems in philosophy <strong>of</strong> mind.B. The problem <strong>of</strong> representation is a central part <strong>of</strong> the problem <strong>of</strong> knowledge and an enduring issue inphilosophy <strong>of</strong> mind.1. At the most fundamental ontological level, our experiences <strong>of</strong> the external world are complexarrangements <strong>of</strong> matter and energy.2. We might ask whether we or a honeybee—whose vision is sensitive to an electromagnetic spectrum towhich we are essentially blind—more accurately “represents” the properties <strong>of</strong> roses and lilies.3. Thus , the question <strong>of</strong> representation can be stated: Is our knowledge <strong>of</strong> objects in the external worlddirect or mediated?©2004 The Teaching Company Limited Partnership 17