Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

Great Ideas of Philosophy

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

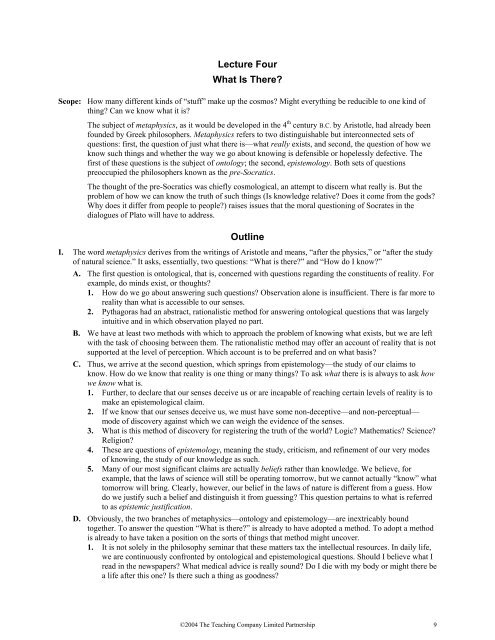

Lecture FourWhat Is There?Scope: How many different kinds <strong>of</strong> “stuff” make up the cosmos? Might everything be reducible to one kind <strong>of</strong>thing? Can we know what it is?The subject <strong>of</strong> metaphysics, as it would be developed in the 4 th century B.C. by Aristotle, had already beenfounded by Greek philosophers. Metaphysics refers to two distinguishable but interconnected sets <strong>of</strong>questions: first, the question <strong>of</strong> just what there is—what really exists, and second, the question <strong>of</strong> how weknow such things and whether the way we go about knowing is defensible or hopelessly defective. Thefirst <strong>of</strong> these questions is the subject <strong>of</strong> ontology; the second, epistemology. Both sets <strong>of</strong> questionspreoccupied the philosophers known as the pre-Socratics.The thought <strong>of</strong> the pre-Socratics was chiefly cosmological, an attempt to discern what really is. But theproblem <strong>of</strong> how we can know the truth <strong>of</strong> such things (Is knowledge relative? Does it come from the gods?Why does it differ from people to people?) raises issues that the moral questioning <strong>of</strong> Socrates in thedialogues <strong>of</strong> Plato will have to address.OutlineI. The word metaphysics derives from the writings <strong>of</strong> Aristotle and means, “after the physics,” or “after the study<strong>of</strong> natural science.” It asks, essentially, two questions: “What is there?” and “How do I know?”A. The first question is ontological, that is, concerned with questions regarding the constituents <strong>of</strong> reality. Forexample, do minds exist, or thoughts?1. How do we go about answering such questions? Observation alone is insufficient. There is far more toreality than what is accessible to our senses.2. Pythagoras had an abstract, rationalistic method for answering ontological questions that was largelyintuitive and in which observation played no part.B. We have at least two methods with which to approach the problem <strong>of</strong> knowing what exists, but we are leftwith the task <strong>of</strong> choosing between them. The rationalistic method may <strong>of</strong>fer an account <strong>of</strong> reality that is notsupported at the level <strong>of</strong> perception. Which account is to be preferred and on what basis?C. Thus, we arrive at the second question, which springs from epistemology—the study <strong>of</strong> our claims toknow. How do we know that reality is one thing or many things? To ask what there is is always to ask howwe know what is.1. Further, to declare that our senses deceive us or are incapable <strong>of</strong> reaching certain levels <strong>of</strong> reality is tomake an epistemological claim.2. If we know that our senses deceive us, we must have some non-deceptive—and non-perceptual—mode <strong>of</strong> discovery against which we can weigh the evidence <strong>of</strong> the senses.3. What is this method <strong>of</strong> discovery for registering the truth <strong>of</strong> the world? Logic? Mathematics? Science?Religion?4. These are questions <strong>of</strong> epistemology, meaning the study, criticism, and refinement <strong>of</strong> our very modes<strong>of</strong> knowing, the study <strong>of</strong> our knowledge as such.5. Many <strong>of</strong> our most significant claims are actually beliefs rather than knowledge. We believe, forexample, that the laws <strong>of</strong> science will still be operating tomorrow, but we cannot actually “know” whattomorrow will bring. Clearly, however, our belief in the laws <strong>of</strong> nature is different from a guess. Howdo we justify such a belief and distinguish it from guessing? This question pertains to what is referredto as epistemic justification.D. Obviously, the two branches <strong>of</strong> metaphysics—ontology and epistemology—are inextricably boundtogether. To answer the question “What is there?” is already to have adopted a method. To adopt a methodis already to have taken a position on the sorts <strong>of</strong> things that method might uncover.1. It is not solely in the philosophy seminar that these matters tax the intellectual resources. In daily life,we are continuously confronted by ontological and epistemological questions. Should I believe what Iread in the newspapers? What medical advice is really sound? Do I die with my body or might there bea life after this one? Is there such a thing as goodness?©2004 The Teaching Company Limited Partnership 9