Ninth International Conference on Permafrost ... - IARC Research

Ninth International Conference on Permafrost ... - IARC Research

Ninth International Conference on Permafrost ... - IARC Research

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

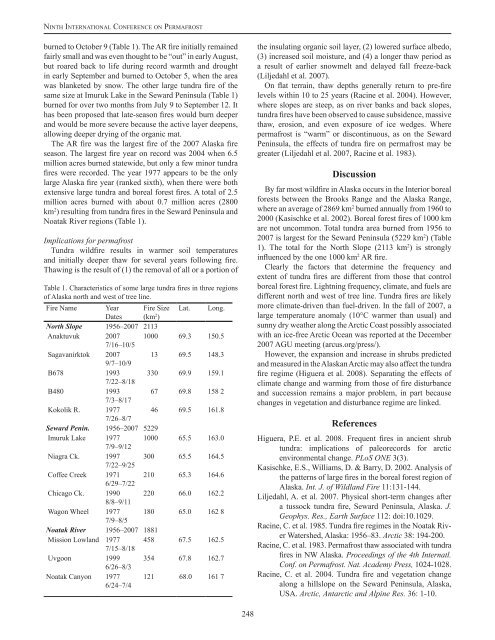

Ni n t h In t e r n at i o n a l Co n f e r e n c e o n Pe r m a f r o s tburned to October 9 (Table 1). The AR fire initially remainedfairly small and was even thought to be “out” in early August,but roared back to life during record warmth and droughtin early September and burned to October 5, when the areawas blanketed by snow. The other large tundra fire of thesame size at Imuruk Lake in the Seward Peninsula (Table 1)burned for over two m<strong>on</strong>ths from July 9 to September 12. Ithas been proposed that late-seas<strong>on</strong> fires would burn deeperand would be more severe because the active layer deepens,allowing deeper drying of the organic mat.The AR fire was the largest fire of the 2007 Alaska fireseas<strong>on</strong>. The largest fire year <strong>on</strong> record was 2004 when 6.5milli<strong>on</strong> acres burned statewide, but <strong>on</strong>ly a few minor tundrafires were recorded. The year 1977 appears to be the <strong>on</strong>lylarge Alaska fire year (ranked sixth), when there were bothextensive large tundra and boreal forest fires. A total of 2.5milli<strong>on</strong> acres burned with about 0.7 milli<strong>on</strong> acres (2800km 2 ) resulting from tundra fires in the Seward Peninsula andNoatak River regi<strong>on</strong>s (Table 1).Implicati<strong>on</strong>s for permafrostTundra wildfire results in warmer soil temperaturesand initially deeper thaw for several years following fire.Thawing is the result of (1) the removal of all or a porti<strong>on</strong> ofTable 1. Characteristics of some large tundra fires in three regi<strong>on</strong>sof Alaska north and west of tree line.Fire Name Year Fire Size Lat. L<strong>on</strong>g.Dates (km 2 )North Slope 1956–2007 2113Anaktuvuk 2007 1000 69.3 150.57/16–10/5Sagavanirktok 2007 13 69.5 148.39/7–10/9B678 1993 330 69.9 159.17/22–8/18B480 1993 67 69.8 158 27/3–8/17Kokolik R. 1977 46 69.5 161.87/26–8/7Seward Penin. 1956–2007 5229Imuruk Lake 1977 1000 65.5 163.07/9–9/12Niagra Ck. 1997 300 65.5 164.57/22–9/25Coffee Creek 1971 210 65.3 164.66/29–7/22Chicago Ck. 1990 220 66.0 162.28/8–9/11Wag<strong>on</strong> Wheel 1977 180 65.0 162 87/9–8/5Noatak River 1956–2007 1881Missi<strong>on</strong> Lowland 1977 458 67.5 162.57/15–8/18Uvgo<strong>on</strong> 1999 354 67.8 162.76/26–8/3Noatak Cany<strong>on</strong> 19776/24–7/4121 68.0 161 7the insulating organic soil layer, (2) lowered surface albedo,(3) increased soil moisture, and (4) a l<strong>on</strong>ger thaw period asa result of earlier snowmelt and delayed fall freeze-back(Liljedahl et al. 2007).On flat terrain, thaw depths generally return to pre-firelevels within 10 to 25 years (Racine et al. 2004). However,where slopes are steep, as <strong>on</strong> river banks and back slopes,tundra fires have been observed to cause subsidence, massivethaw, erosi<strong>on</strong>, and even exposure of ice wedges. Wherepermafrost is “warm” or disc<strong>on</strong>tinuous, as <strong>on</strong> the SewardPeninsula, the effects of tundra fire <strong>on</strong> permafrost may begreater (Liljedahl et al. 2007, Racine et al. 1983).Discussi<strong>on</strong>By far most wildfire in Alaska occurs in the Interior borealforests between the Brooks Range and the Alaska Range,where an average of 2869 km 2 burned annually from 1960 to2000 (Kasischke et al. 2002). Boreal forest fires of 1000 kmare not uncomm<strong>on</strong>. Total tundra area burned from 1956 to2007 is largest for the Seward Peninsula (5229 km 2 ) (Table1). The total for the North Slope (2113 km 2 ) is str<strong>on</strong>glyinfluenced by the <strong>on</strong>e 1000 km 2 AR fire.Clearly the factors that determine the frequency andextent of tundra fires are different from those that c<strong>on</strong>trolboreal forest fire. Lightning frequency, climate, and fuels aredifferent north and west of tree line. Tundra fires are likelymore climate-driven than fuel-driven. In the fall of 2007, alarge temperature anomaly (10°C warmer than usual) andsunny dry weather al<strong>on</strong>g the Arctic Coast possibly associatedwith an ice-free Arctic Ocean was reported at the December2007 AGU meeting (arcus.org/press/).However, the expansi<strong>on</strong> and increase in shrubs predictedand measured in the Alaskan Arctic may also affect the tundrafire regime (Higuera et al. 2008). Separating the effects ofclimate change and warming from those of fire disturbanceand successi<strong>on</strong> remains a major problem, in part becausechanges in vegetati<strong>on</strong> and disturbance regime are linked.ReferencesHiguera, P.E. et al. 2008. Frequent fires in ancient shrubtundra: implicati<strong>on</strong>s of paleorecords for arcticenvir<strong>on</strong>mental change. PLoS ONE 3(3).Kasischke, E.S., Williams, D. & Barry, D. 2002. Analysis ofthe patterns of large fires in the boreal forest regi<strong>on</strong> ofAlaska. Int. J. of Wildland Fire 11:131-144.Liljedahl, A. et al. 2007. Physical short-term changes aftera tussock tundra fire, Seward Peninsula, Alaska. J.Geophys. Res., Earth Surface 112: doi:10.1029.Racine, C. et al. 1985. Tundra fire regimes in the Noatak RiverWatershed, Alaska: 1956–83. Arctic 38: 194-200.Racine, C. et al. 1983. <strong>Permafrost</strong> thaw associated with tundrafires in NW Alaska. Proceedings of the 4th Internatl.C<strong>on</strong>f. <strong>on</strong> <strong>Permafrost</strong>. Nat. Academy Press, 1024-1028.Racine, C. et al. 2004. Tundra fire and vegetati<strong>on</strong> changeal<strong>on</strong>g a hillslope <strong>on</strong> the Seward Peninsula, Alaska,USA. Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Res. 36: 1-10.248