Poverty Dimensions of Public Governance and Forest Management ...

Poverty Dimensions of Public Governance and Forest Management ...

Poverty Dimensions of Public Governance and Forest Management ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

14<br />

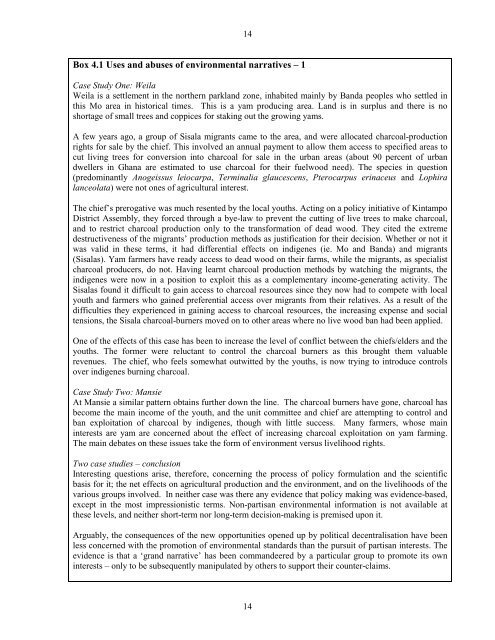

Box 4.1 Uses <strong>and</strong> abuses <strong>of</strong> environmental narratives – 1<br />

Case Study One: Weila<br />

Weila is a settlement in the northern parkl<strong>and</strong> zone, inhabited mainly by B<strong>and</strong>a peoples who settled in<br />

this Mo area in historical times. This is a yam producing area. L<strong>and</strong> is in surplus <strong>and</strong> there is no<br />

shortage <strong>of</strong> small trees <strong>and</strong> coppices for staking out the growing yams.<br />

A few years ago, a group <strong>of</strong> Sisala migrants came to the area, <strong>and</strong> were allocated charcoal-production<br />

rights for sale by the chief. This involved an annual payment to allow them access to specified areas to<br />

cut living trees for conversion into charcoal for sale in the urban areas (about 90 percent <strong>of</strong> urban<br />

dwellers in Ghana are estimated to use charcoal for their fuelwood need). The species in question<br />

(predominantly Anogeissus leiocarpa, Terminalia glaucescens, Pterocarpus erinaceus <strong>and</strong> Lophira<br />

lanceolata) were not ones <strong>of</strong> agricultural interest.<br />

The chief’s prerogative was much resented by the local youths. Acting on a policy initiative <strong>of</strong> Kintampo<br />

District Assembly, they forced through a bye-law to prevent the cutting <strong>of</strong> live trees to make charcoal,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to restrict charcoal production only to the transformation <strong>of</strong> dead wood. They cited the extreme<br />

destructiveness <strong>of</strong> the migrants’ production methods as justification for their decision. Whether or not it<br />

was valid in these terms, it had differential effects on indigenes (ie. Mo <strong>and</strong> B<strong>and</strong>a) <strong>and</strong> migrants<br />

(Sisalas). Yam farmers have ready access to dead wood on their farms, while the migrants, as specialist<br />

charcoal producers, do not. Having learnt charcoal production methods by watching the migrants, the<br />

indigenes were now in a position to exploit this as a complementary income-generating activity. The<br />

Sisalas found it difficult to gain access to charcoal resources since they now had to compete with local<br />

youth <strong>and</strong> farmers who gained preferential access over migrants from their relatives. As a result <strong>of</strong> the<br />

difficulties they experienced in gaining access to charcoal resources, the increasing expense <strong>and</strong> social<br />

tensions, the Sisala charcoal-burners moved on to other areas where no live wood ban had been applied.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the effects <strong>of</strong> this case has been to increase the level <strong>of</strong> conflict between the chiefs/elders <strong>and</strong> the<br />

youths. The former were reluctant to control the charcoal burners as this brought them valuable<br />

revenues. The chief, who feels somewhat outwitted by the youths, is now trying to introduce controls<br />

over indigenes burning charcoal.<br />

Case Study Two: Mansie<br />

At Mansie a similar pattern obtains further down the line. The charcoal burners have gone, charcoal has<br />

become the main income <strong>of</strong> the youth, <strong>and</strong> the unit committee <strong>and</strong> chief are attempting to control <strong>and</strong><br />

ban exploitation <strong>of</strong> charcoal by indigenes, though with little success. Many farmers, whose main<br />

interests are yam are concerned about the effect <strong>of</strong> increasing charcoal exploitation on yam farming.<br />

The main debates on these issues take the form <strong>of</strong> environment versus livelihood rights.<br />

Two case studies – conclusion<br />

Interesting questions arise, therefore, concerning the process <strong>of</strong> policy formulation <strong>and</strong> the scientific<br />

basis for it; the net effects on agricultural production <strong>and</strong> the environment, <strong>and</strong> on the livelihoods <strong>of</strong> the<br />

various groups involved. In neither case was there any evidence that policy making was evidence-based,<br />

except in the most impressionistic terms. Non-partisan environmental information is not available at<br />

these levels, <strong>and</strong> neither short-term nor long-term decision-making is premised upon it.<br />

Arguably, the consequences <strong>of</strong> the new opportunities opened up by political decentralisation have been<br />

less concerned with the promotion <strong>of</strong> environmental st<strong>and</strong>ards than the pursuit <strong>of</strong> partisan interests. The<br />

evidence is that a ‘gr<strong>and</strong> narrative’ has been comm<strong>and</strong>eered by a particular group to promote its own<br />

interests – only to be subsequently manipulated by others to support their counter-claims.<br />

14