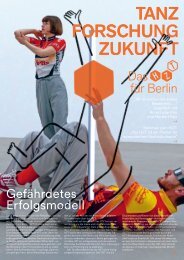

Dance Techniques 2010

What does today's contemporary dance training look like? Seven research teams at well known European dance universities have tackled this question by working with and querying some of contemporary dance s most important teachers: Alan Danielson, Humphrey/Limón Tradition, Anouk van Dijk, Countertechnique, Barbara Passow, Jooss Leeder Technique, Daniel Roberts Cunningham Technique, Gill Clarke Minding Motion, Jennifer Muller Muller Technique, Lance Gries Release and Alignment Oriented Techniques. This comprehensive study includes interviews, scholarly contributions, and supplementary essays, as well as video recordings and lesson plans. It provides a comparative look into historical contexts, movement characteristics, concepts, and teaching methods. A workbook with two training DVDs for anyone involved in dance practice and theory. Ingo Diehl, Friederike Lampert (Eds.), Dance Techniques 2010 – Tanzplan Germany. With two DVDs. Berlin: Henschel 2011. ISBN 978-3-89487-689-0 (Englisch) Out of print.

What does today's contemporary dance training look like? Seven research teams at well known European dance universities have tackled this question by working with and querying some of contemporary dance s most important teachers: Alan Danielson, Humphrey/Limón Tradition, Anouk van Dijk, Countertechnique, Barbara Passow, Jooss Leeder Technique, Daniel Roberts Cunningham Technique, Gill Clarke Minding Motion, Jennifer Muller Muller Technique, Lance Gries Release and Alignment Oriented Techniques.

This comprehensive study includes interviews, scholarly contributions, and supplementary essays, as well as video recordings and lesson plans. It provides a comparative look into historical contexts, movement characteristics, concepts, and teaching methods. A workbook with two training DVDs for anyone involved in dance practice and theory.

Ingo Diehl, Friederike Lampert (Eds.), Dance Techniques 2010 – Tanzplan Germany. With two DVDs. Berlin: Henschel 2011. ISBN 978-3-89487-689-0 (Englisch) Out of print.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

216 Understanding the Body / Movement<br />

Gill Clarke, Franz Anton Cramer, Gisela Müller<br />

Understanding the<br />

Body / Movement<br />

Prerequisites<br />

“Maybe any kind of previous experience with somatic<br />

practice and a sensibility for what it means to<br />

change patterns or habits is useful. But basically, there is<br />

no single definition of what might enhance the learning<br />

effect. On the contrary, it seems rather obvious that even<br />

beginners can enter this exploratory process (maybe they<br />

would be less able to integrate it in their own practice).”<br />

group comment<br />

More than a physical disposition, participants should<br />

bring a mental disposition that will encourage immersion<br />

in an exploratory process through which one can discover<br />

and learn. This includes a willingness to sustain attention<br />

on one activity rather than shift restlessly from one to the<br />

next, and to allow time for digestion and incorporation of<br />

experience. The learning process is facilitated by the individual<br />

dancer focusing their energy on the present moment<br />

and developing mental stamina to sustain attention to the<br />

details of their movement. A readiness to switch / flip / swap<br />

between different phases of work and states of attention,<br />

and maybe even from performance to studying, is equally<br />

important. All of these elements add up to a disposition<br />

that understands learning as a state of playfulness (albeit<br />

serious in scope), and allows for an appreciation of process<br />

as well as result.<br />

The balancing act in the teaching process is often made<br />

more delicate because of the varied backgrounds and experiences<br />

of the students. Some dancers will be well attuned<br />

to diving into the playful and nonjudgemental<br />

mindset necessary to learn through experience, and may<br />

find the questioning, or testing of alternatives less familiar<br />

territory; others will find it harder to open up their mental<br />

focus beyond the rational, analytical, or physical, and to<br />

experience their movement sensorially. 13<br />

Minding Motion can be practiced both by professional<br />

dancers, dance and movement students, and by amateurs.<br />

There are no particular physical skills required before embarking<br />

on this work. Nonetheless, Minding Motion will<br />

most often support dancers / performers in finding and refining<br />

their own practice and physical discipline. The work<br />

can also be a source for improvisation and for the generation<br />

of movement material that can be integrated into<br />

choreographic practice.<br />

However, a recurrent element called talking–through<br />

complements personal sensing and discovery of movement<br />

qualities with a reflective approach. Differential qualities<br />

are suggested, never imposed. Each individual directs their<br />

13 See Claxton, 1997 on the role of different<br />

modes of thought in learning.<br />

14 Forsythe, 2003.<br />

15 Comparison to spatial concepts can be<br />

found in: Concept and Ideology, Imagining the<br />

Body, keyword ‘Space’.<br />

16 For more detail, see Teaching: Principles<br />

and Methodology later in this chapter.<br />

17 See also Pallasmaa, 2005.