Dance Techniques 2010

What does today's contemporary dance training look like? Seven research teams at well known European dance universities have tackled this question by working with and querying some of contemporary dance s most important teachers: Alan Danielson, Humphrey/Limón Tradition, Anouk van Dijk, Countertechnique, Barbara Passow, Jooss Leeder Technique, Daniel Roberts Cunningham Technique, Gill Clarke Minding Motion, Jennifer Muller Muller Technique, Lance Gries Release and Alignment Oriented Techniques. This comprehensive study includes interviews, scholarly contributions, and supplementary essays, as well as video recordings and lesson plans. It provides a comparative look into historical contexts, movement characteristics, concepts, and teaching methods. A workbook with two training DVDs for anyone involved in dance practice and theory. Ingo Diehl, Friederike Lampert (Eds.), Dance Techniques 2010 – Tanzplan Germany. With two DVDs. Berlin: Henschel 2011. ISBN 978-3-89487-689-0 (Englisch) Out of print.

What does today's contemporary dance training look like? Seven research teams at well known European dance universities have tackled this question by working with and querying some of contemporary dance s most important teachers: Alan Danielson, Humphrey/Limón Tradition, Anouk van Dijk, Countertechnique, Barbara Passow, Jooss Leeder Technique, Daniel Roberts Cunningham Technique, Gill Clarke Minding Motion, Jennifer Muller Muller Technique, Lance Gries Release and Alignment Oriented Techniques.

This comprehensive study includes interviews, scholarly contributions, and supplementary essays, as well as video recordings and lesson plans. It provides a comparative look into historical contexts, movement characteristics, concepts, and teaching methods. A workbook with two training DVDs for anyone involved in dance practice and theory.

Ingo Diehl, Friederike Lampert (Eds.), Dance Techniques 2010 – Tanzplan Germany. With two DVDs. Berlin: Henschel 2011. ISBN 978-3-89487-689-0 (Englisch) Out of print.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

50<br />

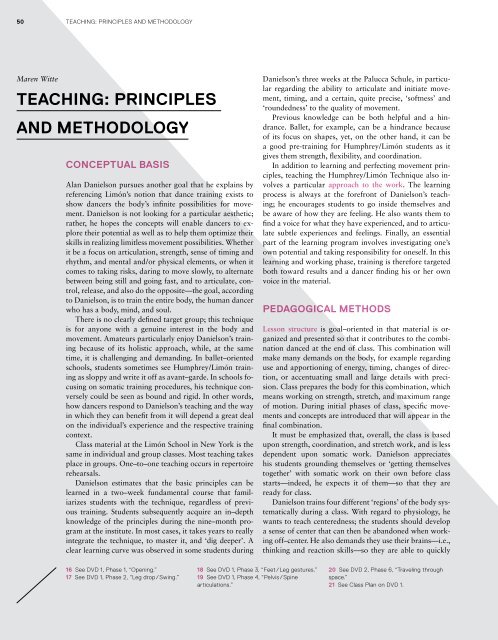

Teaching: Principles and Methodology<br />

Maren Witte<br />

Teaching: Principles<br />

and Methodology<br />

Conceptual Basis<br />

Alan Danielson pursues another goal that he explains by<br />

referencing Limón’s notion that dance training exists to<br />

show dancers the body’s infinite possibilities for movement.<br />

Danielson is not looking for a particular aesthetic;<br />

rather, he hopes the concepts will enable dancers to explore<br />

their potential as well as to help them optimize their<br />

skills in realizing limitless movement possibilities. Whether<br />

it be a focus on articulation, strength, sense of timing and<br />

rhythm, and mental and / or physical elements, or when it<br />

comes to taking risks, daring to move slowly, to alternate<br />

between being still and going fast, and to articulate, control,<br />

release, and also do the opposite—the goal, according<br />

to Danielson, is to train the entire body, the human dancer<br />

who has a body, mind, and soul.<br />

There is no clearly defined target group; this technique<br />

is for anyone with a genuine interest in the body and<br />

movement. Amateurs particularly enjoy Danielson’s training<br />

because of its holistic approach, while, at the same<br />

time, it is challenging and demanding. In ballet–oriented<br />

schools, students sometimes see Humphrey / Limón training<br />

as sloppy and write it off as avant–garde. In schools focusing<br />

on somatic training procedures, his technique conversely<br />

could be seen as bound and rigid. In other words,<br />

how dancers respond to Danielson’s teaching and the way<br />

in which they can benefit from it will depend a great deal<br />

on the individual’s experience and the respective training<br />

context.<br />

Class material at the Limón School in New York is the<br />

same in individual and group classes. Most teaching takes<br />

place in groups. One–to–one teaching occurs in repertoire<br />

rehearsals.<br />

Danielson estimates that the basic principles can be<br />

learned in a two–week fundamental course that familiarizes<br />

students with the technique, regardless of previous<br />

training. Students subsequently acquire an in–depth<br />

knowledge of the principles during the nine–month program<br />

at the institute. In most cases, it takes years to really<br />

integrate the technique, to master it, and ‘dig deeper’. A<br />

clear learning curve was observed in some students during<br />

Danielson’s three weeks at the Palucca Schule, in particular<br />

regarding the ability to articulate and initiate movement,<br />

timing, and a certain, quite precise, ‘softness’ and<br />

‘roundedness’ to the quality of movement.<br />

Previous knowledge can be both helpful and a hindrance.<br />

Ballet, for example, can be a hindrance because<br />

of its focus on shapes, yet, on the other hand, it can be<br />

a good pre-training for Humphrey / Limón students as it<br />

gives them strength, flexibility, and coordination.<br />

In addition to learning and perfecting movement principles,<br />

teaching the Humphrey / Limón Technique also involves<br />

a particular approach to the work. The learning<br />

process is always at the forefront of Danielson’s teaching;<br />

he encourages students to go inside themselves and<br />

be aware of how they are feeling. He also wants them to<br />

find a voice for what they have experienced, and to articulate<br />

subtle experiences and feelings. Finally, an essential<br />

part of the learning program involves investigating one’s<br />

own potential and taking responsibility for oneself. In this<br />

learning and working phase, training is therefore targeted<br />

both toward results and a dancer finding his or her own<br />

voice in the material.<br />

Pedagogical Methods<br />

Lesson structure is goal–oriented in that material is organized<br />

and presented so that it contributes to the combination<br />

danced at the end of class. This combination will<br />

make many demands on the body, for example regarding<br />

use and apportioning of energy, timing, changes of direction,<br />

or accentuating small and large details with precision.<br />

Class prepares the body for this combination, which<br />

means working on strength, stretch, and maximum range<br />

of motion. During initial phases of class, specific movements<br />

and concepts are introduced that will appear in the<br />

final combination.<br />

It must be emphasized that, overall, the class is based<br />

upon strength, coordination, and stretch work, and is less<br />

dependent upon somatic work. Danielson appreciates<br />

his students grounding themselves or ‘getting themselves<br />

together’ with somatic work on their own before class<br />

starts—indeed, he expects it of them—so that they are<br />

ready for class.<br />

Danielson trains four different ‘regions’ of the body systematically<br />

during a class. With regard to physiology, he<br />

wants to teach centeredness; the students should develop<br />

a sense of center that can then be abandoned when working<br />

off–center. He also demands they use their brains—i.e.,<br />

thinking and reaction skills—so they are able to quickly<br />

16 See DVD 1, Phase 1, “Opening.”<br />

17 See DVD 1, Phase 2, “Leg drop / Swing.”<br />

18 See DVD 1, Phase 3, “Feet / Leg gestures.”<br />

19 See DVD 1, Phase 4, “Pelvis / Spine<br />

articulations.”<br />

20 See DVD 2, Phase 6, “Traveling through<br />

space.”<br />

21 See Class Plan on DVD 1.