- Page 1 and 2:

Beyond Time: Temporal and Extra-tem

- Page 3 and 4:

Abstract Beyond Time: Temporal and

- Page 5 and 6:

To Kelvin and Mboshela i

- Page 7 and 8:

and have continued in their support

- Page 9 and 10:

from Veritas Graduate Student Fello

- Page 11 and 12:

2.2.3 Comparison with Proto-BB . .

- Page 13 and 14:

6.5 Summary of analysis of -ite as

- Page 15 and 16:

Glosses Used Gloss Meaning 1 First

- Page 17 and 18:

1.2 Theoretical background and moti

- Page 19 and 20:

Following this general direction, I

- Page 21 and 22:

The first major twentieth-century a

- Page 23 and 24: To make the fuzzy theories more pre

- Page 25 and 26: Multiple degrees of past/future ref

- Page 27 and 28: 1.2.3 Approaches to extra-temporal

- Page 29 and 30: 1.2.3.3 Primary temporal meaning fo

- Page 31 and 32: In their framework, time-based tens

- Page 33 and 34: . fortalééza y-a-cek-íw-a n’aa

- Page 35 and 36: an in-depth diachronic study of Tot

- Page 37 and 38: 1.2.3) may develop at any stage. Th

- Page 39 and 40: within the narrative, “set apart

- Page 41 and 42: without affecting its temporal stru

- Page 43 and 44: Fleisch (2000), and Seidel (2008) d

- Page 45 and 46: . “Indicate episode ends” (Seid

- Page 47 and 48: imperfective, progressive, habitual

- Page 49 and 50: cluding activities, accomplishments

- Page 51 and 52: Some examples of the major categori

- Page 53 and 54: y the speaker’s perception of whe

- Page 55 and 56: P-Domain: D-Domain: Association Dis

- Page 57 and 58: Figure 1.15: Representation without

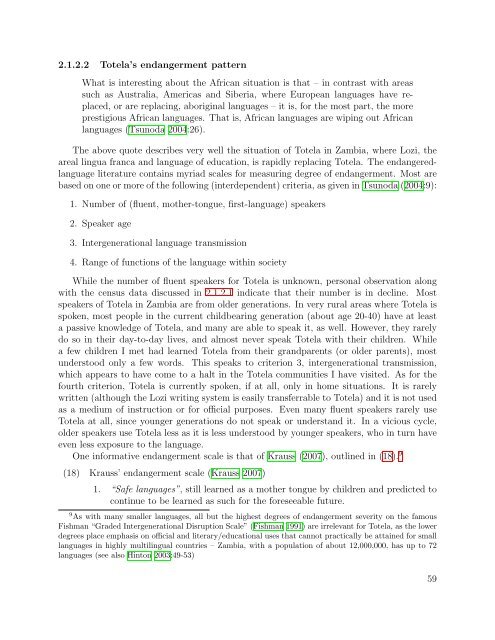

- Page 59 and 60: 1.3.8 Other conventions Following C

- Page 61 and 62: Translations into Lozi were also pr

- Page 63 and 64: 1.4.3 Limitations Although I carrie

- Page 65 and 66: Chapter 5 describes two major marke

- Page 67 and 68: (17) Innovations common to Bantu Bo

- Page 69 and 70: Totela data in de Luna (2008, 2010)

- Page 71 and 72: For more on the historical movement

- Page 73: may be an overrepresentation, since

- Page 77 and 78: officially recognized on a national

- Page 79 and 80: (19) Observed NT dialect continuum:

- Page 81 and 82: ilabial labio- dent. alveolar post-

- Page 83 and 84: Ã Only occurs in NC sequences (see

- Page 85 and 86: ilabial labio- dent. alveolar post-

- Page 87 and 88: 2.2.4.1 Vowel length As noted above

- Page 89 and 90: 2.2.6 Proto-Bantu Correspondences T

- Page 91 and 92: c. *t > s (before *u) *-túmÙ > ò

- Page 93 and 94: (32) *j a. *j > ∅ *-jìtìd > òk

- Page 95 and 96: Although data are not available for

- Page 97 and 98: morphemes typically grammaticalize

- Page 99 and 100: tive. Because the distal can co-occ

- Page 101 and 102: Noun Subject Class Marker 1(a) -mu-

- Page 103 and 104: c. Following u òkùwùlìlà òkù

- Page 105 and 106: òkù-yèndà ‘to walk’ → òk

- Page 107 and 108: (62) a. òkùsàmbìlìlà òkù-s

- Page 109 and 110: (66) Iterative extensions òkùtyò

- Page 111 and 112: (72) Tentive extension òkúkwààt

- Page 113 and 114: c. Negatives with -saka ‘want, li

- Page 115 and 116: c. As source Nòkùlòngàwô kús

- Page 117 and 118: Although all non-verb-final orderin

- Page 119 and 120: (89) abanakazi (aba) bena nabachech

- Page 121 and 122: Sounds Examples PB ZT NT PB ZT NT G

- Page 123 and 124: disappearance. In most cases, vowel

- Page 125 and 126:

2.4.2 NT and ZT: differences in TAM

- Page 127 and 128:

2.4.2.4 Negation FV NT ZT -a indica

- Page 129 and 130:

e studied to evaluate claims about

- Page 131 and 132:

in the prehodiernal past. Similarly

- Page 133 and 134:

maintains the current discourse dom

- Page 135 and 136:

NC Bare Cmpl 1/1a a- a- 2/2a ba- a-

- Page 137 and 138:

(109) a. Atelic durative: ndanenga

- Page 139 and 140:

. Past reading: ndákòmòkwà nda-

- Page 141 and 142:

perception stative -suwa behaves li

- Page 143 and 144:

With activity verbs such as -yenda

- Page 145 and 146:

Totela data than other proposed sol

- Page 147 and 148:

Botne’s description of -ire, in i

- Page 149 and 150:

is formal. As Dahl (1985:129) notes

- Page 151 and 152:

P-Domain: D-Domain: Association Dis

- Page 153 and 154:

(137) a. [Context: the person descr

- Page 155 and 156:

a “path of least effort” in whi

- Page 157 and 158:

ecause the consequences of the past

- Page 159 and 160:

(145) Sunu, twabuuka! Twabuuka ndet

- Page 161 and 162:

3.3.2 -a- with motion verbs in narr

- Page 163 and 164:

(152) Âwò, kàlì mùntù. Ii! N

- Page 165 and 166:

3.3.5 -a- in narrative: summary The

- Page 167 and 168:

verbs, the pathways of development

- Page 169 and 170:

4. With a slight change in accent,

- Page 171 and 172:

Chapter 4 Semantics and Pragmatics

- Page 173 and 174:

These are discussed in section 4.4,

- Page 175 and 176:

. Non-stative predicate: Was macht

- Page 177 and 178:

all require a virtual, fictive read

- Page 179 and 180:

Others (e.g Bybee et al. 1994), in

- Page 181 and 182:

two-state situations, which are mad

- Page 183 and 184:

The choice of modal base and orderi

- Page 185 and 186:

adjacent syllable (to the right) is

- Page 187 and 188:

(189) ìjìlò ndìyá kùmpìlì i

- Page 189 and 190:

(199) chìyùnì (ndìsákà) chiyu

- Page 191 and 192:

Because this chapter deals with the

- Page 193 and 194:

In summary, analysis of the “pres

- Page 195 and 196:

(212) a. ndilabon-a ≈ ndilibwene

- Page 197 and 198:

The -la- marker is also compatible

- Page 199 and 200:

4.3.6 Interactions with situation t

- Page 201 and 202:

4.3.6.3 Duratives With durative (no

- Page 203 and 204:

(232) a. àbá bàyîmbà bàtàbà

- Page 205 and 206:

equirement, situations can either o

- Page 207 and 208:

the [present] is used not so much b

- Page 209 and 210:

In many languages, including Totela

- Page 211 and 212:

otherwise reveal. Non-completive fo

- Page 213 and 214:

are unmarked, as well as presents w

- Page 215 and 216:

the head of his murdered child, fra

- Page 217 and 218:

D.60 (e.g. Ha), and in some M langu

- Page 219 and 220:

-la- lost its disjunctive flavor an

- Page 221 and 222:

(251) tu-la-cita 1pl-pres-do ‘we

- Page 223 and 224:

(253) a. Durative verbs: a-Ø-fik-i

- Page 225 and 226:

Chapter 5 Past and Future: Dissocia

- Page 227 and 228:

groups. While no languages had zero

- Page 229 and 230:

. chìlìmò chàmánà chilimo cha

- Page 231 and 232:

English, for example, future tense

- Page 233 and 234:

differences - both concrete and sub

- Page 235 and 236:

(270) Prehodiernal -ka-: ndàkàsà

- Page 237 and 238:

c. ìjìlò chì-nzí ! ná-mù-li-

- Page 239 and 240:

. ìjìlò nándìlà yá kùmpìl

- Page 241 and 242:

not on the day of perspective time.

- Page 243 and 244:

With both na- and -ka-, the time sp

- Page 245 and 246:

with negation. The lack of -a- mark

- Page 247 and 248:

. ísè19 nándìsíkè nándìlè

- Page 249 and 250:

(303) Iñolo lyenu twakalibona ijil

- Page 251 and 252:

would be similar, but the dissociat

- Page 253 and 254:

5.4 Dissociativity in narrative Bot

- Page 255 and 256:

(310) âwo kàlì mú ! kwáámè n

- Page 257 and 258:

1. In narrator “commentary” abo

- Page 259 and 260:

[In the Guaymí case] the immediate

- Page 261 and 262:

proclitic is still extremely produc

- Page 263 and 264:

(319) hasina bawane amali. . . hasi

- Page 265 and 266:

(321) Progressive uses a. ndìlìy

- Page 267 and 268:

-it-. . . -e. A handful of forms ar

- Page 269 and 270:

(331) chìnzí mwíndìtè? chinzi

- Page 271 and 272:

will be seen below, comparing the u

- Page 273 and 274:

Kratzer (2000) for German stativize

- Page 275 and 276:

. balinunite ba-li-nun-ite 1sg-pres

- Page 277 and 278:

Thus, the distribution of -ite sugg

- Page 279 and 280:

ka- as in (353a), but not with preh

- Page 281 and 282:

A question raised by the characteri

- Page 283 and 284:

Such clashing interpretations arose

- Page 285 and 286:

poses that information structuring

- Page 287 and 288:

6.4.3 -ite’s relevance presupposi

- Page 289 and 290:

Another example is given in (364).

- Page 291 and 292:

(368) handilahupwile bamayo hanu ma

- Page 293 and 294:

. kámbè ndàkàyá ! kwáSàmís

- Page 295 and 296:

. [Context set 1: I am busy. I don

- Page 297 and 298:

6.6.1 -ite’s narrative distributi

- Page 299 and 300:

. Nabo basikuchela shombo nokubona

- Page 301 and 302:

immediate question under discussion

- Page 303 and 304:

(386) Durative root (only perfectiv

- Page 305 and 306:

(389) a. mbá-a-c-éte ‘they came

- Page 307 and 308:

-ile variants for verbs that normal

- Page 309 and 310:

Resultative, especially with COS ve

- Page 311 and 312:

6.7.3.1 Tonga Tonga (M64) has an -i

- Page 313 and 314:

offer him food because he is full (

- Page 315 and 316:

Describes Describes past situation

- Page 317 and 318:

suffixes across Bantu, suggest that

- Page 319 and 320:

7.2 Completion, Tense, and Tenor To

- Page 321 and 322:

espectively. (409c) shows that -na-

- Page 323 and 324:

The intended meaning in (413) can b

- Page 325 and 326:

Figure 7.2: Contentful phase of -sa

- Page 327 and 328:

In short, according to Botne & Kers

- Page 329 and 330:

(426) àwà kándìlàwúkà ndàk

- Page 331 and 332:

. tàkándìtwâ ta-ka-ndi-tu-a neg

- Page 333 and 334:

(440) yùmwí èná òkùlé nèñ

- Page 335 and 336:

7.3.4 “Perfect” meanings Totela

- Page 337 and 338:

. ndìlìnèngètè ndi-li-neng-ete

- Page 339 and 340:

(459) ijilo liizite nandilayenda na

- Page 341 and 342:

Rather than presupposing that a sit

- Page 343 and 344:

This construction appears to treat

- Page 345 and 346:

(483) tàlí mwàyá kwàKàìwàl

- Page 347 and 348:

7.4.3 Hortatives and subjunctives H

- Page 349 and 350:

In general, counterfactual completi

- Page 351 and 352:

(504) buti muponena twali kumisiya

- Page 353 and 354:

(512) Kùyá bùmínà àbántù. K

- Page 355 and 356:

Sometimes, when distal -ka- occurs

- Page 357 and 358:

More likely Less likely to be infle

- Page 359 and 360:

Chapter 8 Conclusion and future res

- Page 361 and 362:

8.2 Directions for future research

- Page 363 and 364:

——. 2007. Stem tone melodies in

- Page 365 and 366:

——, 2010. High-tone anticipatio

- Page 367 and 368:

Glasbey, Sheila. 1998. Progressives

- Page 369 and 370:

Jacottet, Émile. 1896-1901. Étude

- Page 371 and 372:

Morris, Charles W. 1938. Foundation

- Page 373 and 374:

Shirai, Yasuhiro. 1998. Where the p

- Page 375 and 376:

Appendix A Definitions This appendi

- Page 377 and 378:

Information Structure (IS) (followi

- Page 379 and 380:

Time of Situation (TSit) the time f

- Page 381 and 382:

B.2 Consonant mutation: t ¿ s Alth

- Page 383 and 384:

B.5 -ile forms In Totela, only a fe

- Page 385 and 386:

Figure C.1: Downdrift in máyìwíy

- Page 387 and 388:

C.2.1 HTA within words HTA may be s

- Page 389 and 390:

o ku ba hu pu la H H H MR o ku ba h

- Page 391 and 392:

nánkala ‘crab’ echí-fuwa ‘b

- Page 393 and 394:

Syll Ø Root Pattern H Root Pattern

- Page 395 and 396:

Syll Ø Root Pattern H Root Pattern

- Page 397 and 398:

C.33 Persistive -chi- ‘still’ +

- Page 399 and 400:

384 Syll Ø Root Ø Root H Root H R

- Page 401 and 402:

C.7.2 Posited input H on second roo

- Page 403 and 404:

Syll Ø Root H Root 1 ta-ndi-nâ-lw

- Page 405 and 406:

390 Syll Ø Root Ø Root H Root H R

- Page 407 and 408:

C.7.3 Posited input H on final vowe

- Page 409 and 410:

Syll Ø Root H Root 1 ndi-chi-lwâ

- Page 411 and 412:

396 Syll Ø Root Ø Root H Root H R

- Page 413 and 414:

C.7.4 Other patterns Other patterns

- Page 415 and 416:

Appendix D Agreement forms Bantu la

- Page 417 and 418:

Figure D.1 indicates attested singu

- Page 419 and 420:

. bàchìkwàngálà bàlàùlùkà

- Page 421 and 422:

406 NC Prefix SM OM Poss Poss Num A

- Page 423:

Clement Tubusenge, Tiyebulyo Jenika