Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

284 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS Punctuated Equilibrium: A Hopeful Monster 285<br />

mention in <strong>the</strong> first paper <strong>of</strong> any radical <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> speciation or mutation. But<br />

later, about 1980, Gould decided that punctuated equilibrium was a<br />

revolutionary idea after all—not an explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> gradualism in<br />

<strong>the</strong> fossil record, but a refutation <strong>of</strong> Darwinian gradualism itself. This claim<br />

was advertised as revolutionary—<strong>and</strong> now it truly was. It was too revolutionary,<br />

<strong>and</strong> it was hooted down with <strong>the</strong> same sort <strong>of</strong> ferocity <strong>the</strong> establishment<br />

reserves for heretics like Elaine Morgan. Gould backpedaled hard,<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering repeated denials that he had ever meant anything so outrageous. In<br />

that case, responded <strong>the</strong> establishment, <strong>the</strong>re is after all nothing new in what<br />

you say. But wait. Might <strong>the</strong>re be still ano<strong>the</strong>r reading <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis,<br />

according to which it is both true <strong>and</strong> new? There might be. Phase three is<br />

still under way, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> jury is out, considering several different— but all<br />

nonrevolutionary—alternatives. We will have to retrace <strong>the</strong> phases to see<br />

what <strong>the</strong> hue <strong>and</strong> cry has been about.<br />

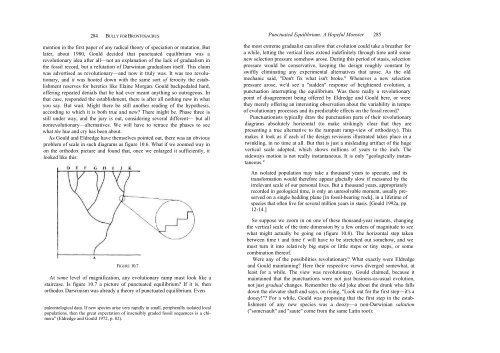

As Gould <strong>and</strong> Eldredge have <strong>the</strong>mselves pointed out, <strong>the</strong>re was an obvious<br />

problem <strong>of</strong> scale in such diagrams as figure 10.6. What if we zoomed way in<br />

on <strong>the</strong> orthodox picture <strong>and</strong> found that, once we enlarged it sufficiently, it<br />

looked like this:<br />

FIGURE 10.7<br />

At some level <strong>of</strong> magnification, any evolutionary ramp must look like a<br />

staircase. Is figure 10.7 a picture <strong>of</strong> punctuated equilibrium? If it is, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

orthodox Darwinism was already a <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> punctuated equilibrium. Even<br />

paleontological data. If new species arise very rapidly in small, peripherally isolated local<br />

populations, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> great expectation <strong>of</strong> insensibly graded fossil sequences is a chimera"<br />

(Eldredge <strong>and</strong> Gould 1972, p. 82).<br />

<strong>the</strong> most extreme gradualist can allow that evolution could take a brea<strong>the</strong>r for<br />

a while, letting <strong>the</strong> vertical lines extend indefinitely through time until some<br />

new selection pressure somehow arose. During this period <strong>of</strong> stasis, selection<br />

pressure would be conservative, keeping <strong>the</strong> design roughly constant by<br />

swiftly eliminating any experimental alternatives that arose. As <strong>the</strong> old<br />

mechanic said, "Don't fix what isn't broke." Whenever a new selection<br />

pressure arose, we'd see a "sudden" response <strong>of</strong> heightened evolution, a<br />

punctuation interrupting <strong>the</strong> equilibrium. Was <strong>the</strong>re really a revolutionary<br />

point <strong>of</strong> disagreement being <strong>of</strong>fered by Eldredge <strong>and</strong> Gould here, or were<br />

<strong>the</strong>y merely <strong>of</strong>fering an interesting observation about <strong>the</strong> variability in tempo<br />

<strong>of</strong> evolutionary processes <strong>and</strong> its predictable effects on <strong>the</strong> fossil record?<br />

Punctuationists typically draw <strong>the</strong> punctuation parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir revolutionary<br />

diagrams absolutely horizontal (to make strikingly clear that <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

presenting a true alternative to <strong>the</strong> rampant ramp-view <strong>of</strong> orthodoxy). This<br />

makes it look as if each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> design revisions illustrated takes place in a<br />

twinkling, in no time at all. But that is just a misleading artifact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> huge<br />

vertical scale adopted, which shows millions <strong>of</strong> years to <strong>the</strong> inch. The<br />

sideways motion is not really instantaneous. It is only "geologically instantaneous."<br />

An isolated population may take a thous<strong>and</strong> years to speciate, <strong>and</strong> its<br />

transformation would <strong>the</strong>refore appear glacially slow if measured by <strong>the</strong><br />

irrelevant scale <strong>of</strong> our personal lives. But a thous<strong>and</strong> years, appropriately<br />

recorded in geological time, is only an unresolvable moment, usually preserved<br />

on a single bedding plane [in fossil-bearing rock], in a lifetime <strong>of</strong><br />

species that <strong>of</strong>ten live for several million years in stasis. [Gould 1992a, pp.<br />

12-14.]<br />

So suppose we zoom in on one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se thous<strong>and</strong>-year instants, changing<br />

<strong>the</strong> vertical scale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time dimension by a few orders <strong>of</strong> magnitude to see<br />

what might actually be going on (figure 10.8). The horizontal step taken<br />

between time t <strong>and</strong> time t' will have to be stretched out somehow, <strong>and</strong> we<br />

must turn it into relatively big steps or little steps or tiny steps, or some<br />

combination <strong>the</strong>re<strong>of</strong>.<br />

Were any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> possibilities revolutionary? What exactly were Eldredge<br />

<strong>and</strong> Gould maintaining? Here <strong>the</strong>ir respective views diverged somewhat, at<br />

least for a while. The view was revolutionary, Gould claimed, because it<br />

maintained that <strong>the</strong> punctuations were not just business-as-usual evolution,<br />

not just gradual changes. Remember <strong>the</strong> old joke about <strong>the</strong> drunk who falls<br />

down <strong>the</strong> elevator shaft <strong>and</strong> says, on rising, "Look out for <strong>the</strong> first step—it's a<br />

doozy!"? For a while, Gould was proposing that <strong>the</strong> first step in <strong>the</strong> establishment<br />

<strong>of</strong> any new species was a doozy—a non-Darwinian saltation<br />

("somersault" <strong>and</strong> "saute" come from <strong>the</strong> same Latin root):