Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

166 PRIMING DARWIN'S PUMP<br />

quite strong that this is <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> case, <strong>and</strong> not just in discussions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropic Principle. Consider <strong>the</strong> related confusions that surround Darwinian<br />

deduction in general. Darwin deduces that human beings must have evolved<br />

from a common ancestor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chimpanzee, or that all life must have arisen<br />

from a single beginning, <strong>and</strong> some people, unaccountably, take <strong>the</strong>se<br />

deductions as claims that human beings are somehow a necessary product <strong>of</strong><br />

evolution, or that life is a necessary feature <strong>of</strong> our planet, but nothing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

kind follows from <strong>Darwin's</strong> deductions properly construed. What must be <strong>the</strong><br />

case is not that we are here, but that since we are here, we evolved from<br />

primates. Suppose John is a bachelor. Then he must be single, right? (That's a<br />

truth <strong>of</strong> logic.) Poor John—he can never get married! The fallacy is obvious<br />

in this example, <strong>and</strong> it is worth keeping it in <strong>the</strong> back <strong>of</strong> your mind as a<br />

template to compare o<strong>the</strong>r arguments with.<br />

Believers in any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> proposed strong versions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Anthropic Principle<br />

think <strong>the</strong>y can deduce something wonderful <strong>and</strong> surprising from <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that we conscious observers are here—for instance, that in some sense<br />

<strong>the</strong> universe exists for us, or perhaps that we exist so that <strong>the</strong> universe as a<br />

whole can exist, or even that God created <strong>the</strong> universe <strong>the</strong> way He did so that<br />

we would be possible. Construed in this way, <strong>the</strong>se proposals are attempts to<br />

restore Paley's Argument from Design, readdressing it to <strong>the</strong> Design <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

universe's most general laws <strong>of</strong> physics, not <strong>the</strong> particular constructions those<br />

laws make possible. Here, once again, Darwinian coun-termoves are<br />

available.<br />

These are deep waters, <strong>and</strong> most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> discussions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues wallow in<br />

technicalities, but <strong>the</strong> logical force <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se Darwinian responses can be<br />

brought out vividly by considering a much simpler case. First, I must introduce<br />

you to <strong>the</strong> Game <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong>, a nifty meme whose principal author is <strong>the</strong><br />

ma<strong>the</strong>matician John Horton Conway. (I will be putting this valuable thinking<br />

tool to several more uses, as we go along. This game does an excellent job <strong>of</strong><br />

taking in a complicated issue <strong>and</strong> reflecting back only <strong>the</strong> dead-simple<br />

essence or skeleton <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issue, ready to be understood <strong>and</strong> appreciated.)<br />

<strong>Life</strong> is played on a two-dimensional grid, such as a checkerboard, using<br />

simple counters, such as pebbles or pennies—or one could go high-tech <strong>and</strong><br />

play it on a computer screen. It is not a game one plays to win; if it is a game<br />

at all, it is solitaire. 4 The grid divides space into square cells, <strong>and</strong> each cell<br />

4. This description <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> is adapted from an eariier exposition <strong>of</strong> mine (1991b). Martin<br />

Gardner introduced <strong>the</strong> Game <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> to a wide audience in two <strong>of</strong> his "Ma<strong>the</strong>matical<br />

Games" columns in Scientific American, in October 1970 <strong>and</strong> February 1971. Poundstone<br />

1985 is an excellent exploration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> game <strong>and</strong> its philosophical implications.<br />

The Laws <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Game <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> 167<br />

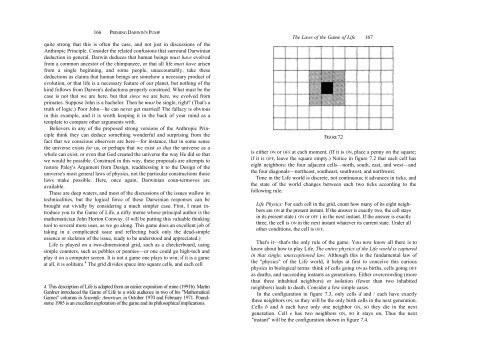

FIGURE 7.2<br />

is ei<strong>the</strong>r ON or OFF at each moment. (If it is ON, place a penny on <strong>the</strong> square;<br />

if it is OFF, leave <strong>the</strong> square empty.) Notice in figure 7.2 that each cell has<br />

eight neighbors: <strong>the</strong> four adjacent cells—north, south, east, <strong>and</strong> west—<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> four diagonals—nor<strong>the</strong>ast, sou<strong>the</strong>ast, southwest, <strong>and</strong> northwest.<br />

Time in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Life</strong> world is discrete, not continuous; it advances in ticks, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world changes between each two ticks according to <strong>the</strong><br />

following rule:<br />

<strong>Life</strong> Physics: For each cell in <strong>the</strong> grid, count how many <strong>of</strong> its eight neighbors<br />

are ON at <strong>the</strong> present instant. If <strong>the</strong> answer is exactly two, <strong>the</strong> cell stays<br />

in its present state ( ON or OFF ) in <strong>the</strong> next instant. If <strong>the</strong> answer is exactly<br />

three, <strong>the</strong> cell is ON in <strong>the</strong> next instant whatever its current state. Under all<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r conditions, <strong>the</strong> cell is OFF.<br />

That's it—that's <strong>the</strong> only rule <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> game. You now know all <strong>the</strong>re is to<br />

know about how to play <strong>Life</strong>. The entire physics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Life</strong> world is captured<br />

in that single, unexceptioned law. Although this is <strong>the</strong> fundamental law <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> "physics" <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Life</strong> world, it helps at first to conceive this curious<br />

physics in biological terms: think <strong>of</strong> cells going ON as births, cells going OFF<br />

as deaths, <strong>and</strong> succeeding instants as generations. Ei<strong>the</strong>r overcrowding (more<br />

than three inhabited neighbors) or isolation (fewer than two inhabited<br />

neighbors) leads to death. Consider a few simple cases.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> configuration in figure 7.3, only cells d <strong>and</strong> / each have exactly<br />

three neighbors ON, so <strong>the</strong>y will be <strong>the</strong> only birth cells in <strong>the</strong> next generation.<br />

Cells b <strong>and</strong> h each have only one neighbor ON, SO <strong>the</strong>y die in <strong>the</strong> next<br />

generation. Cell e has two neighbors ON, SO it stays on. Thus <strong>the</strong> next<br />

"instant" will be <strong>the</strong> configuration shown in figure 7.4.