Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

86 THE TREE OF LIFE How Should We Visualize <strong>the</strong> Tree <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong>? 87<br />

parent organism survives to coexist for a while with its <strong>of</strong>fspring. But such<br />

microdetails <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fan-out will not in general concern us at this time. There<br />

is no serious controversy about <strong>the</strong> fact that all <strong>the</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> life that has<br />

ever existed on this planet is derived from this single fan-out; <strong>the</strong> controversies<br />

arise about how to discover <strong>and</strong> describe in general terms <strong>the</strong> various<br />

forces, principles, constraints, etc., that permit us to give a scientific<br />

explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> patterns in all this diversity.<br />

The Earth is about 4.5 billion years old, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> first life forms appeared<br />

quite "soon"; <strong>the</strong> simplest single-celled organisms—<strong>the</strong> prokaryotes—appeared<br />

at least 35 billion years ago, <strong>and</strong> for probably ano<strong>the</strong>r 2 billion years,<br />

that was all <strong>the</strong> life <strong>the</strong>re was. bacteria, blue-green algae, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir equally<br />

simple kin. Then, about 1.4 billion years ago, a major revolution happened:<br />

some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se simplest life forms literally joined forces, when some bacterialike<br />

prokaryotes invaded <strong>the</strong> membranes <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r prokaryotes, creating <strong>the</strong><br />

eukaryotes—cells with nuclei <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r specialized internal bodies (Margulis<br />

1981). These internal bodies, called organelles or plastids, are <strong>the</strong> key<br />

design innovation opening up <strong>the</strong> regions <strong>of</strong> Design Space inhabited today.<br />

The chloroplasts in plants are responsible for photosyn<strong>the</strong>sis, <strong>and</strong> mitochondria,<br />

which are to be found in every cell <strong>of</strong> every plant, animal,<br />

fungus—every organism with nucleated cells—are <strong>the</strong> fundamental oxygenprocessing<br />

energy-factories that permit us all to fend <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> Second Law <strong>of</strong><br />

Thermodynamics by exploiting <strong>the</strong> materials <strong>and</strong> energy around us. The<br />

prefix "eu" in Greek means "good," <strong>and</strong> from our point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>the</strong> eukaryotes<br />

were certainly an improvement, since, thanks to <strong>the</strong>ir internal<br />

complexity, <strong>the</strong>y could specialize, <strong>and</strong> this eventually made possible <strong>the</strong><br />

creation <strong>of</strong> multicelled organisms, such as ourselves.<br />

That second revolution—<strong>the</strong> emergence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first multicelled organisms—had<br />

to wait 700 million years or so. Once multicelled organisms were<br />

on <strong>the</strong> scene, <strong>the</strong> pace picked up. The subsequent fan-out <strong>of</strong> plants <strong>and</strong><br />

animals—from ferns <strong>and</strong> flowers to insects, reptiles, birds, <strong>and</strong> mammals—<br />

has populated <strong>the</strong> world today with millions <strong>of</strong> different species. In <strong>the</strong><br />

process, millions <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r species have come <strong>and</strong> gone. Surely many more<br />

species have gone extinct than now exist—perhaps a hundred extinct spe-cies<br />

for every existent species.<br />

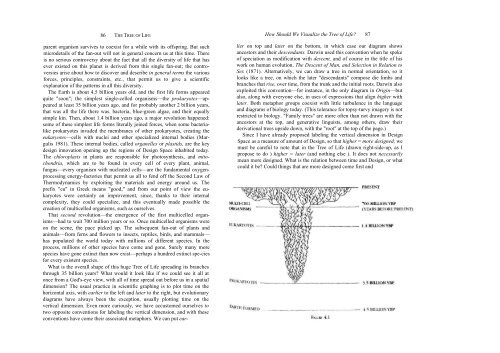

What is <strong>the</strong> overall shape <strong>of</strong> this huge Tree <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> spreading its branches<br />

through 35 billion years? What would it look like if we could see it all at<br />

once from a God's-eye view, with all <strong>of</strong> time spread out before us in a spatial<br />

dimension? The usual practice in scientific graphing is to plot time on <strong>the</strong><br />

horizontal axis, with earlier to <strong>the</strong> left <strong>and</strong> later to <strong>the</strong> right, but evolutionary<br />

diagrams have always been <strong>the</strong> exception, usually plotting time on <strong>the</strong><br />

vertical dimension. Even more curiously, we have accustomed ourselves to<br />

two opposite conventions for labeling <strong>the</strong> vertical dimension, <strong>and</strong> with <strong>the</strong>se<br />

conventions have come <strong>the</strong>ir associated metaphors. We can put ear-<br />

lier on top <strong>and</strong> later on <strong>the</strong> bottom, in which case our diagram shows<br />

ancestors <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir descendants. Darwin used this convention when he spoke<br />

<strong>of</strong> speciation as modification with descent, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> course in <strong>the</strong> title <strong>of</strong> his<br />

work on human evolution, The Descent <strong>of</strong> Man, <strong>and</strong> Selection in Relation to<br />

Sex (1871). Alternatively, we can draw a tree in normal orientation, so it<br />

looks like a tree, on which <strong>the</strong> later "descendants" compose die limbs <strong>and</strong><br />

branches that rise, over time, from <strong>the</strong> trunk <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> initial roots. Darwin also<br />

exploited this convention—for instance, in <strong>the</strong> only diagram in Origin—but<br />

also, along with everyone else, in uses <strong>of</strong> expressions that align higher with<br />

later. Both metaphor groups coexist with little turbulence in <strong>the</strong> language<br />

<strong>and</strong> diagrams <strong>of</strong> biology today. (This tolerance for topsy-turvy imagery is not<br />

restricted to biology. "Family trees" are more <strong>of</strong>ten than not drawn with <strong>the</strong><br />

ancestors at <strong>the</strong> top, <strong>and</strong> generative linguists, among o<strong>the</strong>rs, draw <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

derivational trees upside down, with <strong>the</strong> "root" at <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> page.)<br />

Since I have already proposed labeling <strong>the</strong> vertical dimension in Design<br />

Space as a measure <strong>of</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> Design, so that higher = more designed, we<br />

must be careful to note that in <strong>the</strong> Tree <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> (drawn right-side-up, as I<br />

propose to do ) higher = later (<strong>and</strong> nothing else ). It does not necessarily<br />

mean more designed. What is <strong>the</strong> relation between time <strong>and</strong> Design, or what<br />

could it be? Could things that are more designed come first <strong>and</strong>