Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Darwin's Dangerous Idea - Evolution and the Meaning of Life

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

170 PRIMING DARWIN'S PUMP The Laws <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Game <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> 171<br />

prey usually cannot. If <strong>the</strong> remainder <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> prey dies out as with <strong>the</strong> glider, <strong>the</strong><br />

prey is consumed. [Poundstone 1985, p. 38.]<br />

Notice that something curious happens to our "ontology"—our catalogue <strong>of</strong><br />

what exists—as we move between levels. At <strong>the</strong> physical level <strong>the</strong>re is no<br />

motion, just ON <strong>and</strong> OFF, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> only individual things that exist, cells, are<br />

defined by <strong>the</strong>ir fixed spatial location. At <strong>the</strong> design level we suddenly have<br />

<strong>the</strong> motion <strong>of</strong> persisting objects; it is one <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> same glider (though<br />

composed each generation <strong>of</strong> different cells) that has moved sou<strong>the</strong>ast in<br />

figure 7.6, changing shape as it moves; <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is one less glider in <strong>the</strong><br />

world after <strong>the</strong> eater has eaten it in figure 7.8.<br />

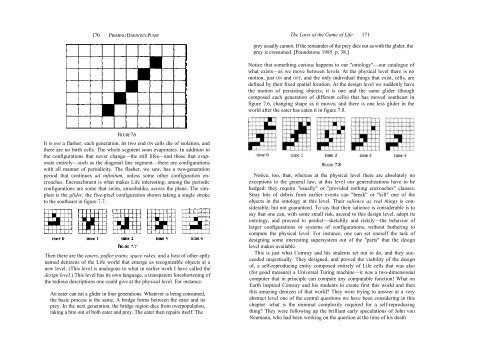

FIGURE 7.6<br />

It is not a flasher; each generation, its two end ON cells die <strong>of</strong> isolation, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>re are no birth cells. The whole segment soon evaporates. In addition to<br />

<strong>the</strong> configurations that never change—<strong>the</strong> still lifes—<strong>and</strong> those that evaporate<br />

entirely—such as <strong>the</strong> diagonal line segment—<strong>the</strong>re are configurations<br />

with all manner <strong>of</strong> periodicity. The flasher, we saw, has a two-generation<br />

period that continues ad infinitum, unless some o<strong>the</strong>r configuration encroaches.<br />

Encroachment is what makes <strong>Life</strong> interesting: among <strong>the</strong> periodic<br />

configurations are some that swim, amoebalike, across <strong>the</strong> plane. The simplest<br />

is <strong>the</strong> glider, <strong>the</strong> five-pixel configuration shown taking a single stroke<br />

to <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast in figure 7.7.<br />

Then <strong>the</strong>re are <strong>the</strong> eaters, puffer trains, space rakes, <strong>and</strong> a host <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r aptly<br />

named denizens <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Life</strong> world that emerge as recognizable objects at a<br />

new level. (This level is analogous to what in earlier work I have called <strong>the</strong><br />

design level.) This level has its own language, a transparent foreshortening <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> tedious descriptions one could give at <strong>the</strong> physical level. For instance:<br />

An eater can eat a glider in four generations. Whatever is being consumed,<br />

<strong>the</strong> basic process is <strong>the</strong> same. A bridge forms between <strong>the</strong> eater <strong>and</strong> its<br />

prey. In <strong>the</strong> next generation, <strong>the</strong> bridge region dies from overpopulation,<br />

taking a bite out <strong>of</strong> both eater <strong>and</strong> prey. The eater <strong>the</strong>n repairs itself. The<br />

Notice, too, that, whereas at <strong>the</strong> physical level <strong>the</strong>re are absolutely no<br />

exceptions to <strong>the</strong> general law, at this level our generalizations have to be<br />

hedged: <strong>the</strong>y require "usually" or "provided nothing encroaches" clauses.<br />

Stray bits <strong>of</strong> debris from earlier events can "break" or "kill" one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

objects in <strong>the</strong> ontology at this level. Their salience as real things is considerable,<br />

but not guaranteed. To say that <strong>the</strong>ir salience is considerable is to<br />

say that one can, with some small risk, ascend to this design level, adopt its<br />

ontology, <strong>and</strong> proceed to predict—sketchily <strong>and</strong> riskily—<strong>the</strong> behavior <strong>of</strong><br />

larger configurations or systems <strong>of</strong> configurations, without bo<strong>the</strong>ring to<br />

compute <strong>the</strong> physical level. For instance, one can set oneself <strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong><br />

designing some interesting supersystem out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> "parts" that <strong>the</strong> design<br />

level makes available.<br />

This is just what Conway <strong>and</strong> his students set out to do, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y succeeded<br />

majestically. They designed, <strong>and</strong> proved <strong>the</strong> viability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> design<br />

<strong>of</strong>, a self-reproducing entity composed entirely <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> cells that was also<br />

(for good measure) a Universal Turing machine—it was a two-dimensional<br />

computer that in principle can compute any computable function! What on<br />

Earth inspired Conway <strong>and</strong> his students to create first this world <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n<br />

this amazing denizen <strong>of</strong> that world? They were trying to answer at a very<br />

abstract level one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> central questions we have been considering in this<br />

chapter: what is <strong>the</strong> minimal complexity required for a self-reproducing<br />

thing? They were following up <strong>the</strong> brilliant early speculations <strong>of</strong> John von<br />

Neumann, who had been working on <strong>the</strong> question at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> his death