- Page 1:

Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie

- Page 4 and 5:

Published in 2008 by Universitätsv

- Page 6 and 7:

Bibliographische Information der De

- Page 9 and 10:

CONTENTS Acknowledgements Prologue

- Page 11:

Contents 5.2 The context of meaning

- Page 14 and 15:

Acknowledgements Many other friends

- Page 16 and 17:

ABBREVIATIONS ADICI Asociación de

- Page 18 and 19:

2 The cultural context of biodivers

- Page 20 and 21:

4 The cultural context of biodivers

- Page 22 and 23:

6 The cultural context of biodivers

- Page 24 and 25:

8 The cultural context of biodivers

- Page 26 and 27:

10 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 28 and 29:

12 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 30 and 31:

14 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 32 and 33:

16 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 34 and 35:

18 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 36 and 37:

20 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 38 and 39:

22 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 40 and 41:

24 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 42 and 43:

26 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 44 and 45:

28 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 46 and 47:

30 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 48 and 49:

32 The cultural context of biodiver

- Page 51 and 52:

3 THE DISCURSIVE CONTEXT - conceptu

- Page 53 and 54:

The discursive context paradigms ar

- Page 55 and 56:

The discursive context environmenta

- Page 57 and 58:

The discursive context of pluralist

- Page 59 and 60:

The discursive context mental chang

- Page 61 and 62:

The discursive context and the ›s

- Page 63 and 64:

The discursive context More critica

- Page 65 and 66:

The discursive context 3.1.3 Concep

- Page 67 and 68:

The discursive context ristic power

- Page 69 and 70:

The discursive context Given the hi

- Page 71 and 72:

The discursive context frame that g

- Page 73 and 74:

The discursive context agencies eng

- Page 75 and 76:

The discursive context In the end,

- Page 77 and 78:

The discursive context entific cred

- Page 79 and 80:

The discursive context in a protect

- Page 81 and 82:

The discursive context Wells and Br

- Page 83 and 84:

The discursive context accelerated

- Page 85 and 86:

The discursive context Beyond its s

- Page 87 and 88:

The discursive context tivity that

- Page 89 and 90:

The discursive context a religious

- Page 91 and 92:

The discursive context The sense of

- Page 93 and 94:

The discursive context to us as adu

- Page 95 and 96:

The discursive context In this way,

- Page 97 and 98:

The discursive context concurrence.

- Page 99 and 100:

The discursive context In discussin

- Page 101 and 102:

The discursive context In the same

- Page 103 and 104:

The discursive context efforts payi

- Page 105 and 106:

The discursive context 3.4.1 The co

- Page 107 and 108:

The discursive context In order to

- Page 109 and 110:

The discursive context Apart from t

- Page 111 and 112:

The discursive context and organisi

- Page 113 and 114:

The discursive context 3.4.3 The sy

- Page 115 and 116:

The discursive context terms throug

- Page 117 and 118:

The discursive context Nevertheless

- Page 119 and 120:

The discursive context hypotheses.

- Page 121 and 122:

The discursive context for a partic

- Page 123 and 124:

The discursive context tions with t

- Page 125 and 126:

4 THE LOCAL CONTEXT - national poli

- Page 127 and 128:

The local context 4.1.1 Biological

- Page 129 and 130:

The local context Map 4.1 Distribut

- Page 131 and 132:

The local context tions as a counte

- Page 133 and 134:

The local context the area known as

- Page 135 and 136:

The local context Moreover, the ret

- Page 137 and 138:

The local context 4.2 The Maya-Q'eq

- Page 139 and 140:

The local context The integration o

- Page 141 and 142:

The local context 4.2.2 Historical

- Page 143 and 144:

The local context In the early 1980

- Page 145 and 146: The local context 4.3 The conservat

- Page 147 and 148: The local context Fig. 4.6 A view f

- Page 149 and 150: The local context 4.3.2 The co-mana

- Page 151 and 152: The local context Fig. 4.7 Discussi

- Page 153 and 154: The local context poor condition of

- Page 155 and 156: The local context 4.4.2 Methodologi

- Page 157 and 158: The local context not specify the r

- Page 159 and 160: The local context lowed to witness

- Page 161 and 162: 5 LOCAL EXPRESSIONS OF INDIGENOUS K

- Page 163 and 164: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 165 and 166: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 167 and 168: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 169 and 170: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 171 and 172: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 173 and 174: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 175 and 176: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 177 and 178: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 179 and 180: Local expressions of indigenous kno

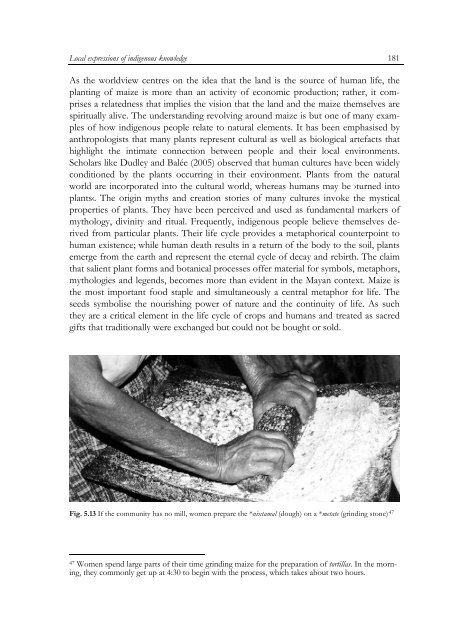

- Page 181 and 182: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 183 and 184: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 185 and 186: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 187 and 188: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 189 and 190: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 191 and 192: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 193 and 194: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 195: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 199 and 200: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 201 and 202: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 203 and 204: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 205 and 206: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 207 and 208: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 209 and 210: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 211 and 212: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 213 and 214: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 215 and 216: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 217 and 218: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 219 and 220: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 221 and 222: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 223 and 224: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 225 and 226: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 227 and 228: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 229 and 230: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 231 and 232: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 233 and 234: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 235 and 236: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 237 and 238: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 239 and 240: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 241 and 242: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 243 and 244: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 245 and 246: Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 247 and 248:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 249 and 250:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 251 and 252:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 253 and 254:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 255 and 256:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 257 and 258:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 259 and 260:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 261 and 262:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 263:

Local expressions of indigenous kno

- Page 266 and 267:

250 The cultural context of biodive

- Page 268 and 269:

252 The cultural context of biodive

- Page 271 and 272:

EPILOGUE At the end of my last stay

- Page 273 and 274:

REFERENCES

- Page 275 and 276:

References Atran, Scott et al. (200

- Page 277 and 278:

References Brush, Stephen B. & Dore

- Page 279 and 280:

References Dove, Michael (1996). Ce

- Page 281 and 282:

References Gari, Josep-Antoni (2000

- Page 283 and 284:

References Hajer, Maarten & Frank F

- Page 285 and 286:

References Kockelman, Paul (2003).

- Page 287 and 288:

References Messer, Ellen (2001). Th

- Page 289 and 290:

References Oviedo, Gonzalo/Luisa Ma

- Page 291 and 292:

References Redford, Kent/Katrina Br

- Page 293 and 294:

References — (2002a). Participant

- Page 295 and 296:

References UNEP-WCMC (2003). Tradit

- Page 297 and 298:

APPENDIX

- Page 299:

Appendix Map 4.3 Alta Verapaz and m

- Page 302 and 303:

Göttinger Studien zur Ethnologie h