- Page 1 and 2: Australian Dietary Guidelines Incor

- Page 3 and 4: Australian Dietary Guidelines Austr

- Page 5 and 6: 2.4.4 Practical considerations: Lea

- Page 7 and 8: 1. Introduction 1.1 Why the Guideli

- Page 9 and 10: income, education, cultural influen

- Page 11 and 12: The Evidence Report (A review of th

- Page 13 and 14: 1.4 How the Guidelines were develop

- Page 15 and 16: Levels of evidence in public health

- Page 17 and 18: the study results were generalisabl

- Page 19 and 20: Table 1.1: Changes in macronutrient

- Page 21 and 22: population. NHMRC intends to work w

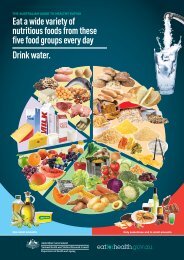

- Page 23 and 24: Figure 1.2: Australian Guide to Hea

- Page 25 and 26: Executive Summary Dietary patterns

- Page 27: Consuming a wide variety of foods m

- Page 31 and 32: 2.1.4.6 People in lower socioeconom

- Page 33 and 34: vegetable intake and cancer has foc

- Page 35 and 36: Endometrial, Ovarian and pancreatic

- Page 37 and 38: 2.2.3.2 Cancer Colorectal cancer: E

- Page 39 and 40: 2.2.4.2 Cancer Alimentary tract can

- Page 41 and 42: 2.2.5.2 Cancer mechanisms There is

- Page 43 and 44: Table 2.1: Recommended number of se

- Page 45 and 46: increasing appetites. Unless prescr

- Page 47 and 48: 2.3.2.1 Cardiovascular disease, typ

- Page 49 and 50: Table 2.3: Recommended number of se

- Page 51 and 52: 2.4 Lean meat and poultry, fish, eg

- Page 53 and 54: interpret because of widely varying

- Page 55 and 56: 2.4.2.3.1 Fish: Cardiovascular dise

- Page 57 and 58: Smoked, salted and chemically prese

- Page 59 and 60: Depending on age and sex, health be

- Page 61 and 62: 2.4.4.6 Vegetarians For several nut

- Page 63 and 64: Evidence Statement Grade Consumptio

- Page 65 and 66: 2.5.3 How drinking milk and eating

- Page 67 and 68: 2.5.4.1 Pregnant and breastfeeding

- Page 69 and 70: the recent review [14]. Many common

- Page 71 and 72: 2.6.2.3 Other conditions Dental car

- Page 73 and 74: Where to next Both the quality and

- Page 75 and 76: Executive summary This Guideline em

- Page 77 and 78: 3.1.2 The evidence for ‘limiting

- Page 79 and 80:

In the longer term, the review cond

- Page 81 and 82:

The P:M:S ratio is a useful tool in

- Page 83 and 84:

3.2.2 The evidence for ‘limiting

- Page 85 and 86:

3.2.3 How limiting intake of foods

- Page 87 and 88:

3.2.4.4 Older people Taste percepti

- Page 89 and 90:

No large studies have measured the

- Page 91 and 92:

Excess weight: Many foods containin

- Page 93 and 94:

etter health outcomes than those wh

- Page 95 and 96:

Evidence Statement Grade Consumptio

- Page 97 and 98:

Dementia: The evidence suggests an

- Page 99 and 100:

Drinking coffee, having a cold show

- Page 101 and 102:

In the absence of any research to q

- Page 103 and 104:

Executive summary Healthy weight is

- Page 105 and 106:

prevalence of obesity alone is high

- Page 107 and 108:

Compared to having a BMI between 18

- Page 109 and 110:

4.1.3.2 Energy intake and trend dat

- Page 111 and 112:

4.1.3.4 Energy intake from specific

- Page 113 and 114:

4.1.4.2 Benefits of physical activi

- Page 115 and 116:

4.2.1 Primary prevention Diet and p

- Page 117 and 118:

and consistent evidence that dietar

- Page 119 and 120:

4.2.2 Secondary prevention Behaviou

- Page 121 and 122:

Table 4.4 A stepped model for the m

- Page 123 and 124:

Taller or larger and more active ad

- Page 125 and 126:

Table 4.5 2010 Institute of Medicin

- Page 127 and 128:

For older, taller or more active ch

- Page 129 and 130:

Most older people will benefit from

- Page 131 and 132:

5. Encourage and support breastfeed

- Page 133 and 134:

5.1 Setting the scene The World Hea

- Page 135 and 136:

Evidence Statement Grade Exclusive

- Page 137 and 138:

Table 5.1 Factors associated with d

- Page 139 and 140:

5.2.4 Other benefits Sudden Infant

- Page 141 and 142:

5.3.1.3 Mothers in the workplace Ev

- Page 143 and 144:

5.3.1.3 Community support The succe

- Page 145 and 146:

Executive summary More than five mi

- Page 147 and 148:

[929]. Fresh fruit and vegetables c

- Page 149 and 150:

contamination (see above) avoided.

- Page 151 and 152:

1989 - 1995 Composition of Foods, A

- Page 153 and 154:

2001 Eat Well Australia: An Agenda

- Page 155 and 156:

2011 A Review of the Evidence to Ad

- Page 157 and 158:

Professor Dorothy Mackerras Dr Dav

- Page 159 and 160:

Level III-2 - A comparative study w

- Page 161 and 162:

food options to meet additional ene

- Page 163 and 164:

Appendix 3. Assessing growth and he

- Page 165 and 166:

Table A3.1 International BMI cut-of

- Page 167 and 168:

A3.1.6 Z-scores and percentiles: Co

- Page 169 and 170:

Appendix 4. Physical activity guide

- Page 171 and 172:

Suggested activities include: mode

- Page 173 and 174:

Appendix 5. Studies examining the h

- Page 175 and 176:

that further specific studies are r

- Page 177 and 178:

Table A6.2 Energy and alcohol conte

- Page 179 and 180:

The economic, social and cultural f

- Page 181 and 182:

A diet consistent with the Guidelin

- Page 183 and 184:

In other more recent studies, highe

- Page 185 and 186:

A7.4 Aboriginal and Torres Strait I

- Page 187 and 188:

A7.4.3.2. Aboriginal people living

- Page 189 and 190:

Mortality rates for people born ove

- Page 191 and 192:

Appendix 8: Glossary Adequate Intak

- Page 193 and 194:

Carbohydrates Carbohydrates are pol

- Page 195 and 196:

Exclusive breastfeeding Means an in

- Page 197 and 198:

Legume/Beans Refers to all forms of

- Page 199 and 200:

Older adults For the purposes of th

- Page 201 and 202:

Reduced fat products For a food to

- Page 203 and 204:

celery and asparagus), gourd vegeta

- Page 205 and 206:

Evidence Statement Grade Fruit Cons

- Page 207 and 208:

Table A9.2: Evidence statements (Gr

- Page 209 and 210:

References 1. Rayner, M. and P. Sca

- Page 211 and 212:

27. Wilkinson, R. and M. Marmot, So

- Page 213 and 214:

54. Hawkins, S.S., T.J. Cole, and C

- Page 215 and 216:

81. Hesketh, K., M. Wake, and E. Wa

- Page 217 and 218:

107. McCullough, M.L., et al., Diet

- Page 219 and 220:

135. Brimblecombe, J.K. and K. O’

- Page 221 and 222:

162. Kreimer, A.R., et al., Diet an

- Page 223 and 224:

189. Ward, H.A., et al., Breast, co

- Page 225 and 226:

216. Paolini, M., et al., Beta-caro

- Page 227 and 228:

244. Kelly, S.A., et al., Wholegrai

- Page 229 and 230:

270. Williams, P.G., et al., Cereal

- Page 231 and 232:

297. Garcia-Closas, R., et al., Foo

- Page 233 and 234:

324. Maclean, C.H., et al., Effects

- Page 235 and 236:

349. Vander Wal, J.S., et al., Egg

- Page 237 and 238:

376. Elwood, P.C., et al., The surv

- Page 239 and 240:

404. Javaid, M.K., et al., Maternal

- Page 241 and 242:

430. Lagiou, P., et al., Intake of

- Page 243 and 244:

458. Vartanian, L.R., M.B. Schwartz

- Page 245 and 246:

486. Lopez-Ridaura, R., et al., Mag

- Page 247 and 248:

512. Kratz, M., et al., The impact

- Page 249 and 250:

537. Daniels, S.R. and F.R. Greer,

- Page 251 and 252:

562. Cook, N.R., et al., Joint effe

- Page 253 and 254:

588. Burt, B.A., et al., The effect

- Page 255 and 256:

615. Ronksley, P.E., et al., Associ

- Page 257 and 258:

642. Purdue, M.P., et al., Type of

- Page 259 and 260:

669. Arntzen, K., et al., Moderate

- Page 261 and 262:

696. Rokholm, B., J.L. Baker, and T

- Page 263 and 264:

724. Bensimhon, D.R., W.E. Kraus, a

- Page 265 and 266:

750. Centre for Epidemiology and Re

- Page 267 and 268:

776. Monasta, L., et al., Early-lif

- Page 269 and 270:

803. Prentice, A.M. and S.A. Jebb,

- Page 271 and 272:

830. Callaway, L.K., et al., The pr

- Page 273 and 274:

857. Australian Institute of Health

- Page 275 and 276:

885. Demmelmair, H., J. von Rosen,

- Page 277 and 278:

911. Duong, D.V., C.W. Binns, and A

- Page 279 and 280:

940. Cashel K, L.J., NUTTAB89-Nutri

- Page 281 and 282:

http://www.health.gov.au/internet/m

- Page 283 and 284:

995. Atlantis, E., E.H. Barnes, and

- Page 285 and 286:

1021. Australian Bureau of Statisti

- Page 287 and 288:

1049. Altman, J., Hunter-gatherers