Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone - IRIT

Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone - IRIT

Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone - IRIT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

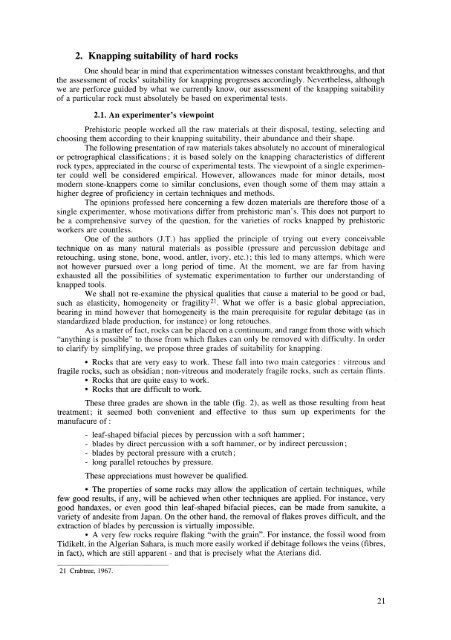

2. Knappin g suitability o f hard rocks<br />

One should bear in mind that experimentation witnesses constant breakthroughs, <strong>and</strong> that<br />

the assessment <strong>of</strong> rocks' suitability for knapping progresses accordingly. Nevertheless, although<br />

we are perforce guided by what we currently know, our assessment <strong>of</strong> the knapping suitability<br />

<strong>of</strong> a particular rock must absolutely be based on experimental tests.<br />

2.1. A n experimenter' s viewpoin t<br />

Prehistoric people worked all the raw materials at their disposal, testing, selecting <strong>and</strong><br />

choosing them according to their knapping suitability, their abundance <strong>and</strong> their shape.<br />

The following presentation <strong>of</strong> raw materials takes absolutely no account <strong>of</strong> mineralogical<br />

or petrographical classifications; it is based solely on the knapping characteristics <strong>of</strong> different<br />

rock types, appreciated in the course <strong>of</strong> experimental tests. The viewpoint <strong>of</strong> a single experimenter<br />

could well be considered empirical. However, allowances made for minor details, most<br />

modern stone-knappers come to similar conclusions, even though some <strong>of</strong> them may attain a<br />

higher degree <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>iciency in certain techniques <strong>and</strong> methods.<br />

The opinions pr<strong>of</strong>essed here concerning a few dozen materials are therefore those <strong>of</strong> a<br />

single experimenter, whose motivations differ from prehistoric man's. This does not purport to<br />

be a comprehensive survey <strong>of</strong> the question, for the varieties <strong>of</strong> rocks knapped by prehistoric<br />

workers are countless.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the authors (J.T.) has applied the principle <strong>of</strong> trying out every conceivable<br />

technique on as many natural materials as possible (pressure <strong>and</strong> percussion debitage <strong>and</strong><br />

retouching, using stone, bone, wood, antler, ivory, etc.); this led to many attemps, which were<br />

not however pursued over a long period <strong>of</strong> time. At the moment, we are far from having<br />

exhausted all the possibilities <strong>of</strong> systematic experimentation to further our underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong><br />

knapped tools.<br />

We shall not re-examine the physical qualities that cause a material to be good or bad,<br />

such as elasticity, homogeneity or fragility 21<br />

. What we <strong>of</strong>fer is a basic global appreciation,<br />

bearing in mind however that homogeneity is the main prerequisite for regular debitage (as in<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ardized blade production, for instance) or long retouches.<br />

As a matter <strong>of</strong> fact, rocks can be placed on a continuum, <strong>and</strong> range from those with which<br />

"anything is possible" to those from which flakes can only be removed with difficulty. In order<br />

to clarify by simplifying, we propose three grades <strong>of</strong> suitability for knapping.<br />

• Rocks that are very easy to work. These fall into two main categories : vitreous <strong>and</strong><br />

fragile rocks, such as obsidian; non-vitreous <strong>and</strong> moderately fragile rocks, such as certain flints.<br />

• Rocks that are quite easy to work.<br />

• Rocks that are difficult to work.<br />

These three grades are shown in the table (fig. 2), as well as those resulting from heat<br />

treatment; it seemed both convenient <strong>and</strong> effective to thus sum up experiments for the<br />

manufacure <strong>of</strong>:<br />

- leaf-shaped bifacial pieces by percussion with a s<strong>of</strong>t hammer;<br />

- blades by direct percussion with a s<strong>of</strong>t hammer, or by indirect percussion;<br />

- blades by pectoral pressure with a crutch;<br />

- long parallel retouches by pressure.<br />

These appreciations must however be qualified.<br />

• The properties <strong>of</strong> some rocks may allow the application <strong>of</strong> certain techniques, while<br />

few good results, if any, will be achieved when other techniques are applied. For instance, very<br />

good h<strong>and</strong>axes, or even good thin leaf-shaped bifacial pieces, can be made from sanukite, a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong>esite from Japan. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, the removal <strong>of</strong> flakes proves difficult, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

extraction <strong>of</strong> blades by percussion is virtually impossible.<br />

• A very few rocks require flaking "with the grain". For instance, the fossil wood from<br />

Tidikelt, in the Algerian Sahara, is much more easily worked if debitage follows the veins (fibres,<br />

in fact), which are still apparent - <strong>and</strong> that is precisely what the Aterians did.<br />

21 Crabtree, 1967.<br />

21