Blazing New Trails - Connexions

Blazing New Trails - Connexions

Blazing New Trails - Connexions

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

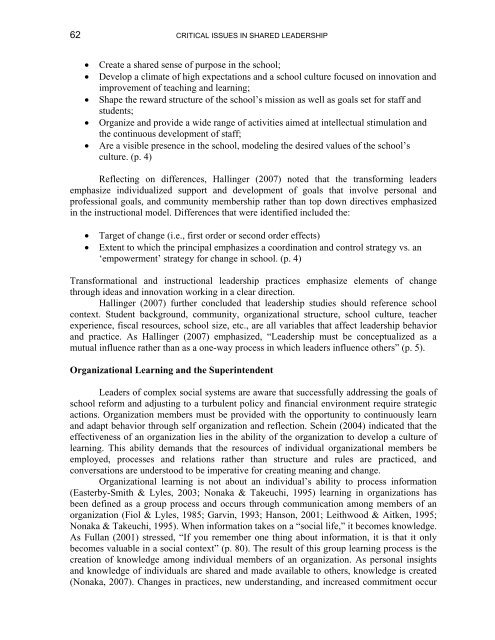

62 CRITICAL ISSUES IN SHARED LEADERSHIP<br />

Create a shared sense of purpose in the school;<br />

Develop a climate of high expectations and a school culture focused on innovation and<br />

improvement of teaching and learning;<br />

Shape the reward structure of the school’s mission as well as goals set for staff and<br />

students;<br />

Organize and provide a wide range of activities aimed at intellectual stimulation and<br />

the continuous development of staff;<br />

Are a visible presence in the school, modeling the desired values of the school’s<br />

culture. (p. 4)<br />

Reflecting on differences, Hallinger (2007) noted that the transforming leaders<br />

emphasize individualized support and development of goals that involve personal and<br />

professional goals, and community membership rather than top down directives emphasized<br />

in the instructional model. Differences that were identified included the:<br />

Target of change (i.e., first order or second order effects)<br />

Extent to which the principal emphasizes a coordination and control strategy vs. an<br />

‘empowerment’ strategy for change in school. (p. 4)<br />

Transformational and instructional leadership practices emphasize elements of change<br />

through ideas and innovation working in a clear direction.<br />

Hallinger (2007) further concluded that leadership studies should reference school<br />

context. Student background, community, organizational structure, school culture, teacher<br />

experience, fiscal resources, school size, etc., are all variables that affect leadership behavior<br />

and practice. As Hallinger (2007) emphasized, “Leadership must be conceptualized as a<br />

mutual influence rather than as a one-way process in which leaders influence others” (p. 5).<br />

Organizational Learning and the Superintendent<br />

Leaders of complex social systems are aware that successfully addressing the goals of<br />

school reform and adjusting to a turbulent policy and financial environment require strategic<br />

actions. Organization members must be provided with the opportunity to continuously learn<br />

and adapt behavior through self organization and reflection. Schein (2004) indicated that the<br />

effectiveness of an organization lies in the ability of the organization to develop a culture of<br />

learning. This ability demands that the resources of individual organizational members be<br />

employed, processes and relations rather than structure and rules are practiced, and<br />

conversations are understood to be imperative for creating meaning and change.<br />

Organizational learning is not about an individual’s ability to process information<br />

(Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 2003; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995) learning in organizations has<br />

been defined as a group process and occurs through communication among members of an<br />

organization (Fiol & Lyles, 1985; Garvin, 1993; Hanson, 2001; Leithwood & Aitken, 1995;<br />

Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). When information takes on a “social life,” it becomes knowledge.<br />

As Fullan (2001) stressed, “If you remember one thing about information, it is that it only<br />

becomes valuable in a social context” (p. 80). The result of this group learning process is the<br />

creation of knowledge among individual members of an organization. As personal insights<br />

and knowledge of individuals are shared and made available to others, knowledge is created<br />

(Nonaka, 2007). Changes in practices, new understanding, and increased commitment occur