Effectiveness and Economic Impact of Tax Incentives in the SADC ...

Effectiveness and Economic Impact of Tax Incentives in the SADC ...

Effectiveness and Economic Impact of Tax Incentives in the SADC ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

3-12 EFFECTIVENESS AND IMPACT OF TAX INCENTIVES IN THE <strong>SADC</strong> REGION<br />

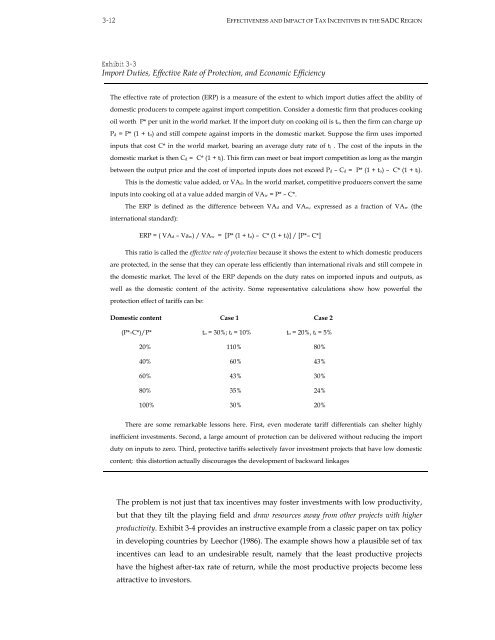

Exhibit 3-3<br />

Import Duties, Effective Rate <strong>of</strong> Protection, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> Efficiency<br />

The effective rate <strong>of</strong> protection (ERP) is a measure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extent to which import duties affect <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong><br />

domestic producers to compete aga<strong>in</strong>st import competition. Consider a domestic firm that produces cook<strong>in</strong>g<br />

oil worth P* per unit <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world market. If <strong>the</strong> import duty on cook<strong>in</strong>g oil is to, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> firm can charge up<br />

Pd = P* (1 + to) <strong>and</strong> still compete aga<strong>in</strong>st imports <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> domestic market. Suppose <strong>the</strong> firm uses imported<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts that cost C* <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world market, bear<strong>in</strong>g an average duty rate <strong>of</strong> ti . The cost <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>puts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

domestic market is <strong>the</strong>n Cd = C* (1 + ti). This firm can meet or beat import competition as long as <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong><br />

between <strong>the</strong> output price <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> imported <strong>in</strong>puts does not exceed Pd – Cd = P* (1 + to) – C* (1 + ti).<br />

This is <strong>the</strong> domestic value added, or VAd. In <strong>the</strong> world market, competitive producers convert <strong>the</strong> same<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts <strong>in</strong>to cook<strong>in</strong>g oil at a value added marg<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> VAw = P* – C*.<br />

The ERP is def<strong>in</strong>ed as <strong>the</strong> difference between VAd <strong>and</strong> VAw, expressed as a fraction <strong>of</strong> VAw (<strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational st<strong>and</strong>ard):<br />

ERP = ( VAd – Vaw) / VAw = [P* (1 + to) – C* (1 + ti)] / [P*– C*]<br />

This ratio is called <strong>the</strong> effective rate <strong>of</strong> protection because it shows <strong>the</strong> extent to which domestic producers<br />

are protected, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sense that <strong>the</strong>y can operate less efficiently than <strong>in</strong>ternational rivals <strong>and</strong> still compete <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> domestic market. The level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ERP depends on <strong>the</strong> duty rates on imported <strong>in</strong>puts <strong>and</strong> outputs, as<br />

well as <strong>the</strong> domestic content <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> activity. Some representative calculations show how powerful <strong>the</strong><br />

protection effect <strong>of</strong> tariffs can be:<br />

Domestic content Case 1 Case 2<br />

(P*-C*)/P* to = 30%; ti = 10% to = 20%, ti = 5%<br />

20% 110% 80%<br />

40% 60% 43%<br />

60% 43% 30%<br />

80% 35% 24%<br />

100% 30% 20%<br />

There are some remarkable lessons here. First, even moderate tariff differentials can shelter highly<br />

<strong>in</strong>efficient <strong>in</strong>vestments. Second, a large amount <strong>of</strong> protection can be delivered without reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> import<br />

duty on <strong>in</strong>puts to zero. Third, protective tariffs selectively favor <strong>in</strong>vestment projects that have low domestic<br />

content; this distortion actually discourages <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> backward l<strong>in</strong>kages<br />

The problem is not just that tax <strong>in</strong>centives may foster <strong>in</strong>vestments with low productivity,<br />

but that <strong>the</strong>y tilt <strong>the</strong> play<strong>in</strong>g field <strong>and</strong> draw resources away from o<strong>the</strong>r projects with higher<br />

productivity. Exhibit 3-4 provides an <strong>in</strong>structive example from a classic paper on tax policy<br />

<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries by Leechor (1986). The example shows how a plausible set <strong>of</strong> tax<br />

<strong>in</strong>centives can lead to an undesirable result, namely that <strong>the</strong> least productive projects<br />

have <strong>the</strong> highest after-tax rate <strong>of</strong> return, while <strong>the</strong> most productive projects become less<br />

attractive to <strong>in</strong>vestors.