- Page 4 and 5:

Cover Artwork: Long-tailed Blue But

- Page 7 and 8:

LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1. Gross Dome

- Page 9 and 10:

Figure 41. Number of Students Invol

- Page 11 and 12:

Figure 85. Proportion of Babies Bor

- Page 13 and 14:

Figure 127. Relationship Between th

- Page 15:

Table 21. Policy Documents Relevant

- Page 19:

Table 108. Proportion of Young Peop

- Page 23 and 24:

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEWIntroducti

- Page 25 and 26:

three then reviews mental health is

- Page 27 and 28:

Table 1. Overview of the Determinan

- Page 29 and 30:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 31 and 32:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 33 and 34:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 35 and 36:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 37 and 38:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 39 and 40:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 41 and 42:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 43:

Stream Indicator New Zealand Distri

- Page 47:

47MACROECONOMICINDICATORS

- Page 50 and 51:

Expenditure-based Measure of GDPThe

- Page 52 and 53:

Gini Coefficient: The Lorenz curve

- Page 54 and 55:

CHILD POVERTY AND LIVING STANDARDSI

- Page 56 and 57:

After Housing Costs (AHC)Relative P

- Page 58 and 59:

Figure 8. Proportion of Dependent C

- Page 60 and 61:

14 Items (Enforced Lacks) are inclu

- Page 62 and 63:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 64 and 65:

Other Relevant New Zealand Evidence

- Page 66 and 67:

UNEMPLOYMENT RATESIntroductionIn th

- Page 68 and 69:

Figure 12. Unemployment Rates by Ag

- Page 70 and 71:

Unemployment Rates by Qualification

- Page 72 and 73:

Figure 18. Quarterly Unemployment R

- Page 74 and 75:

CHILDREN RELIANT ON BENEFIT RECIPIE

- Page 76 and 77:

Table 4. Number of Children Aged 0-

- Page 78 and 79:

Table 5. Number of Children Aged 0-

- Page 80 and 81:

YOUNG PEOPLE RELIANT ON BENEFITSInt

- Page 82 and 83:

Table 7. Number of Young People Age

- Page 84 and 85:

New Zealand Distribution by Ethnici

- Page 86 and 87:

Figure 25. Young People Aged 16-24

- Page 88 and 89:

Table 10. Number of Young People Ag

- Page 91:

HOUSEHOLD COMPOSITION91

- Page 94 and 95:

Data Source and MethodsDefinitionPr

- Page 96 and 97:

Figure 29. Proportion of Children A

- Page 98 and 99:

Robertson J, et al. 2006. Review of

- Page 100 and 101:

Canadian National Occupancy Standar

- Page 102 and 103:

Figure 33. Proportion of Children a

- Page 104 and 105:

Other Relevant EvidenceMarmot Revie

- Page 106 and 107:

106

- Page 108 and 109:

108

- Page 110 and 111:

Note 2: The number of new school en

- Page 112 and 113:

Figure 36. Proportion of New Entran

- Page 114 and 115:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 116 and 117:

Sylva K, et al. 2004 The Effective

- Page 118 and 119:

Table 15. Enrolments in Māori Medi

- Page 120 and 121:

Table 16. Number of Students (Māor

- Page 122 and 123:

Local Policy Documents which Consid

- Page 124 and 125:

HIGHEST EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT AT S

- Page 126 and 127:

Figure 43. Highest Educational Atta

- Page 128 and 129:

Figure 46. Highest Educational Atta

- Page 130 and 131:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 132 and 133:

SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL RETENTION A

- Page 134 and 135:

Participation in Tertiary Education

- Page 136 and 137:

Midland Region Distribution and Tre

- Page 138 and 139:

The following section uses informat

- Page 140 and 141:

Figure 54. Age-Standardised Rates o

- Page 142 and 143:

Figure 56. Age-Standardised School

- Page 144 and 145:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 146 and 147:

TRUANCY AND UNJUSTIFIED ABSENCESInt

- Page 148 and 149:

Figure 60. Total Unjustified Absenc

- Page 150 and 151:

Figure 63. Total Unjustified Absenc

- Page 152 and 153:

152

- Page 154 and 155:

154

- Page 156 and 157:

156

- Page 158 and 159:

Table 22. The National Immunisation

- Page 160 and 161:

Figure 64. Immunisation Coverage by

- Page 162:

Figure 67. Immunisation Coverage by

- Page 165 and 166:

Figure 71. Immunisation Coverage at

- Page 167 and 168:

Soares-Weiser K, et al. 2012. Vacci

- Page 169 and 170:

Briss PA, et al. 2000. Reviews of e

- Page 171 and 172:

Data Sources and MethodsIndicatorPr

- Page 173 and 174:

Figure 75. Proportion of New Zealan

- Page 175 and 176:

Proportion Receiving Core Contacts

- Page 177 and 178:

Figure 81. Proportion of Babies who

- Page 179 and 180:

The B4 School CheckThe B4 School Ch

- Page 181 and 182:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 183 and 184:

Other Relevant EvidenceThe Scottish

- Page 185 and 186:

185SUBSTANCE USE

- Page 188 and 189:

Notes on InterpretationNote 1: The

- Page 190 and 191:

Maternal Smoking at First Registrat

- Page 192 and 193:

Figure 86. Proportion of Babies Bor

- Page 194 and 195:

Table 32. Number of Cigarettes Smok

- Page 196 and 197:

Figure 88. Proportion of Babies Bor

- Page 198 and 199:

National Institute for Health and C

- Page 200 and 201:

2. Proportion of babies born to mot

- Page 202 and 203:

Figure 90. Proportion of Babies Bor

- Page 204 and 205:

Table 37. Number of Cigarettes Smok

- Page 206 and 207:

Figure 92. Proportion of Babies Bor

- Page 208 and 209:

Figure 93. Proportion of Year 10 St

- Page 210 and 211:

Figure 95. Proportion of Year 10 St

- Page 212 and 213:

TOBACCO USE IN YOUNG PEOPLEIntroduc

- Page 214 and 215:

Figure 96. Daily Smoking Rates in Y

- Page 216 and 217:

2009 New Zealand Tobacco Use Survey

- Page 218 and 219:

Source of Tobacco in the Last Month

- Page 220 and 221:

Carson KV, et al. 2011. Community i

- Page 222 and 223:

Other Relevant PublicationsMāori A

- Page 224 and 225:

Other Cochrane Systematic Reviews o

- Page 226 and 227:

ALCOHOL-RELATED HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS

- Page 228 and 229:

Figure 100. Alcohol-Related Hospita

- Page 230 and 231:

Table 45. Listed External Causes of

- Page 232 and 233:

Midland Region Distribution and Tre

- Page 234 and 235:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 236 and 237:

Shults RA, et al. 2009. Effectivene

- Page 238 and 239:

238

- Page 240 and 241:

240

- Page 242 and 243:

242

- Page 244 and 245:

Mortality from conditions with a so

- Page 246 and 247:

Table 50. Mortality from Conditions

- Page 248 and 249:

Figure 105. Hospital Admissions for

- Page 250 and 251:

Midland Region Distribution and Tre

- Page 252 and 253:

Table 55. Hospital Admissions for C

- Page 254 and 255: Table 57. Hospital Admissions for C

- Page 256 and 257: Midland Region Distribution by Caus

- Page 258 and 259: Figure 107. Hospital Admissions for

- Page 260 and 261: INFANT MORTALITY AND SUDDEN UNEXPEC

- Page 262 and 263: New Zealand Distribution and Trends

- Page 264 and 265: Figure 111. Total Infant Mortality,

- Page 266 and 267: Table 62. Neonatal and Post Neonata

- Page 268 and 269: Table 65. Neonatal and Post Neonata

- Page 270 and 271: Distribution by Ethnicity, NZ Depri

- Page 272 and 273: Figure 116. Sudden Unexpected Death

- Page 274 and 275: Vennemann M, et al. 2007. Do immuni

- Page 276 and 277: 276

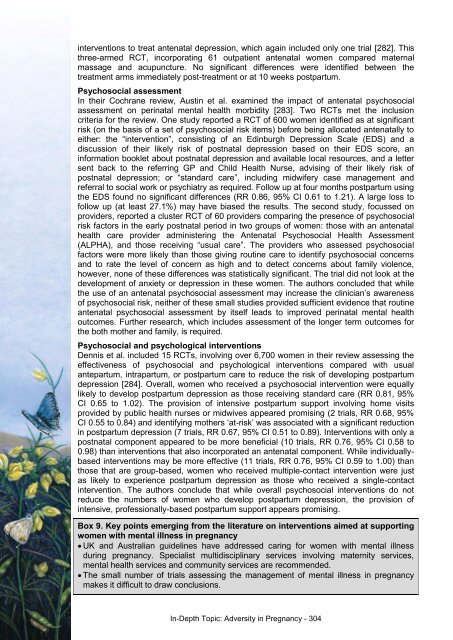

- Page 278 and 279: with a review of interventions aime

- Page 280 and 281: deprivation in some parts of the wo

- Page 282 and 283: who delay a second pregnancy by two

- Page 284 and 285: Family ViolenceDefinitions and New

- Page 286 and 287: need for multidisciplinary interven

- Page 288 and 289: 6 days to determine gestational age

- Page 290 and 291: In New Zealand, information on fact

- Page 292 and 293: post intervention. Engagement in ed

- Page 294 and 295: antenatal care, including two nutri

- Page 296 and 297: throughout pregnancy, birth and the

- Page 298 and 299: Alcohol and Other DrugsNational and

- Page 300 and 301: Zealand had a number of specialist

- Page 302 and 303: in one Cochrane review [274] (see p

- Page 306 and 307: In ConclusionWhile it is hoped that

- Page 308 and 309: 308

- Page 310 and 311: Data Source and MethodsDefinition1.

- Page 312 and 313: Figure 119. Hospital Admissions for

- Page 314 and 315: Midland Region Distribution and Tre

- Page 316 and 317: Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 318 and 319: Other Systematic ReviewsLouwers ECF

- Page 320 and 321: INJURIES ARISING FROM ASSAULT IN YO

- Page 322 and 323: New Zealand Distribution by Age and

- Page 324 and 325: Midland Region Distribution and Tre

- Page 326 and 327: Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 328 and 329: Flood M & Fergus L. 2008. An Assaul

- Page 330 and 331: Note 2: The numbers in this section

- Page 332 and 333: Table 78. Number of Notifications t

- Page 334 and 335: Table 80. Outcome of Assessment for

- Page 336 and 337: Table 82. Number of Notifications R

- Page 338 and 339: Table 84. Outcome of Assessment for

- Page 340 and 341: Data Source and MethodsDefinition1.

- Page 342 and 343: Family Violence Investigations Wher

- Page 344 and 345: Table 90. Local Policy Documents an

- Page 346 and 347: Stover CS, et al. 2009. Interventio

- Page 348 and 349: 348

- Page 350 and 351: 350

- Page 352 and 353: oader contextual influences on the

- Page 354 and 355:

In addition, Table 112 on Page 414

- Page 356 and 357:

Williams SB, et al. 2009. Screening

- Page 358 and 359:

Ministries of Education, Health, Ju

- Page 360 and 361:

Figure 129. Children and Young Peop

- Page 362 and 363:

Table 92. Children Aged 0-14 Years

- Page 364 and 365:

Table 94. Children Aged 0-14 Years

- Page 366 and 367:

Table 95. Children Aged 0-14 Years

- Page 368 and 369:

IN-DEPTH TOPIC: MENTAL HEALTH ISSUE

- Page 370 and 371:

this [350]. The review stated that

- Page 372 and 373:

psychotic disorders including first

- Page 374 and 375:

Social Workers in SchoolsIn 2011 th

- Page 376 and 377:

Children or young people with sever

- Page 378 and 379:

EpidemiologyThe 2009 review by Meri

- Page 380 and 381:

A diagnosis of conduct disorder acc

- Page 382 and 383:

programme using a questionnaire. Si

- Page 384 and 385:

developmentally appropriate diagnos

- Page 386 and 387:

playthings or the environment, appe

- Page 388 and 389:

state more than it cost) provided t

- Page 390 and 391:

ACCESS TO MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES: L

- Page 392 and 393:

Table 97. Children and Young People

- Page 394 and 395:

Midland Region DistributionChildren

- Page 396 and 397:

ACCESS TO MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES: L

- Page 398 and 399:

Table 101. Hospital Admissions for

- Page 400 and 401:

Numbers Accessing Services by Diagn

- Page 402 and 403:

Table 103. Young People Aged 15-24

- Page 404 and 405:

Table 105. Young People Aged 15-24

- Page 406 and 407:

Table 107. Young People Aged 15-24

- Page 408 and 409:

Table 108. Proportion of Young Peop

- Page 410 and 411:

Table 110. Young People Aged 15-24

- Page 412 and 413:

Midland Region DistributionAmongst

- Page 414 and 415:

Local Policy Documents and Evidence

- Page 416 and 417:

Fletcher A, et al. 2008. School Eff

- Page 418 and 419:

New Zealand Distribution and Trends

- Page 420 and 421:

Figure 138. Mortality from Suicide

- Page 422 and 423:

Figure 139. Mortality from Suicide

- Page 424 and 425:

Ougrin D & Latif S. 2011. Specific

- Page 426 and 427:

426

- Page 428 and 429:

428

- Page 430 and 431:

Guide to Community Preventive Servi

- Page 432 and 433:

information on all of the events oc

- Page 434 and 435:

3. In addition, some providers admi

- Page 436 and 437:

as in the majority of the analyses

- Page 438 and 439:

APPENDIX 5: THE NATIONAL MORTALITYC

- Page 440 and 441:

As a result of these changes, there

- Page 442 and 443:

2. Research also suggests that ethn

- Page 444 and 445:

APPENDIX 8: POLICE AREA BOUNDARIESF

- Page 446 and 447:

Figure 142. Police Area Boundaries

- Page 448 and 449:

3. The condition exhibits a socioec

- Page 450 and 451:

REFERENCES1. Children's Commissione

- Page 452 and 453:

33. Mackay R. 2005. The Impact of F

- Page 454 and 455:

71. Ministry of Health. 2011. Immun

- Page 456 and 457:

107. ASH New Zealand. 2011. Nationa

- Page 458 and 459:

141. Child and Youth Mortality Revi

- Page 460 and 461:

175. Pihama L. 2011. Overview of M

- Page 462 and 463:

208. King-Hele S, Webb RT, Mortense

- Page 464 and 465:

244. Nelson Marlborough District He

- Page 466 and 467:

274. Ramsay J, Carter Y, Davidson L

- Page 468 and 469:

306. Jewkes R. 2002. Intimate partn

- Page 470 and 471:

347. Heflinger CA, Hinshaw SP. 2010

- Page 472 and 473:

376. Ministry of Education. 2012. W

- Page 474 and 475:

410. Ministry of Health. 2001. New

- Page 476 and 477:

443. Zeanah PD, Bailey LO, Berry S.

- Page 478 and 479:

480. Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Beeghly