Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

part ii | states<br />

Outstanding amongst this meagre range <strong>of</strong> artefacts <strong>of</strong> the Achaemenid period<br />

from Central <strong>Asia</strong>’s settled agricultural areas are the numerous objects <strong>of</strong> artistic<br />

culture (small artistic objects – round metal plates, toreutics and jewellery) from the<br />

Amu Darya hoard or Oxus treasure and from the Oxus temple treasure in Takht-i<br />

Sangin. However, if we follow a strictly academic approach, with few exceptions these<br />

objects cannot be regarded as reliable historical sources for describing Achaemenid<br />

art in Central <strong>Asia</strong>. They can only give us an idea <strong>of</strong> the kinds <strong>of</strong> treasures, and <strong>of</strong> the<br />

countries from which they came, before they accumulated in Bactrian temples over<br />

a period <strong>of</strong> several centuries. If we go by the dates when these hoards were hidden,<br />

which was much later than even the end <strong>of</strong> the Achaemenid period, and is connected<br />

to the time <strong>of</strong> Alexander’s conquest <strong>of</strong> Bactria in 329 BC, we can date the artefacts to a<br />

period covering two hundred years. The Amu Darya hoard was most likely concealed<br />

in the 4th century BC, and the Oxus temple hoard on the eve <strong>of</strong> the Yuezhi invasion,<br />

i.e. at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the second half <strong>of</strong> the 2nd century BC. The objects may have<br />

been brought to the temple (or temples?) as votive <strong>of</strong>ferings at any time and could<br />

have come from anywhere.<br />

There is no question about the historical authenticity <strong>of</strong> the objects from the temple<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Oxus in Takht-i Sangin, as the find was documented following<br />

proper archaeological methods. However, doubts about the authenticity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Amu Darya hoard (the Oxus treasure) remain. Strictly speaking, it<br />

is a collection <strong>of</strong> items obtained in various circumstances in Rawalpindi<br />

(Pakistan). Some <strong>of</strong> them do indeed belong to the Amu Darya hoard,<br />

and were possibly found at the Takht-i Qobad site. Other objects,<br />

however, most likely have been collected together at Rawalpindi<br />

but consist <strong>of</strong> possible finds from Gandhara or Kabulistan.<br />

There is also some doubt about the provenance <strong>of</strong> coins that<br />

make up part <strong>of</strong> the treasure, as these were ‘added’ (i.e. described<br />

as belonging to the hoard) by the academic E.V. Zeymal from various<br />

museum collections (whose find-spot is unclear) All the more so<br />

because, to date, no coins from the Greek cities and Achaemenid<br />

satraps <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asia</strong> Minor dating from the 5th–4th centuries BC have been<br />

found in the territory <strong>of</strong> Central <strong>Asia</strong>, including Bactria. Only recently,<br />

apparently, a hoard <strong>of</strong> Achaemenid sigloi was found in southern<br />

Turkmenistan, and some <strong>of</strong> these have ended up in private<br />

collections in Tashkent.<br />

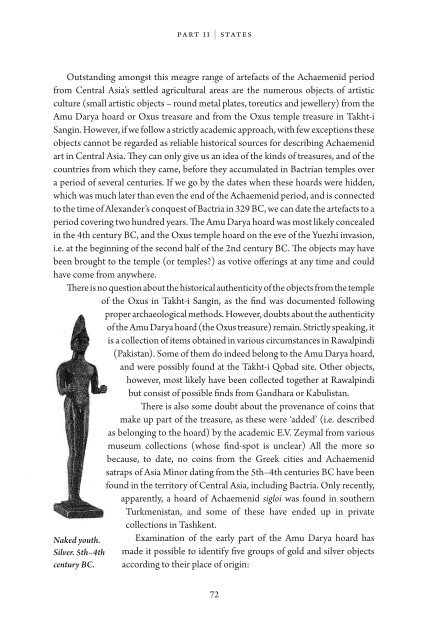

Naked youth.<br />

Silver. 5th–4th<br />

century BC.<br />

Examination <strong>of</strong> the early part <strong>of</strong> the Amu Darya hoard has<br />

made it possible to identify five groups <strong>of</strong> gold and silver objects<br />

according to their place <strong>of</strong> origin:<br />

72