The Canadian Army Journal

The Canadian Army Journal

The Canadian Army Journal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

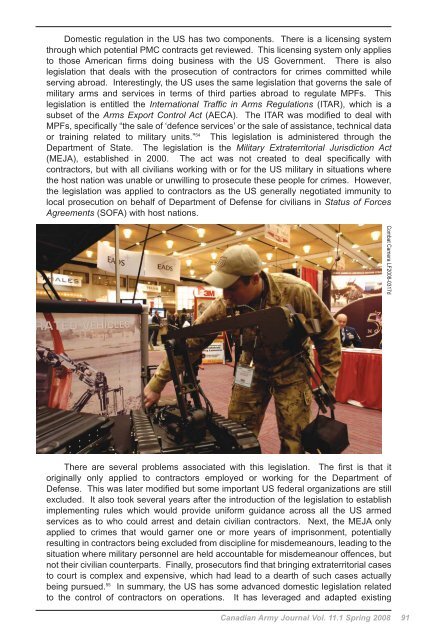

Domestic regulation in the US has two components. <strong>The</strong>re is a licensing system<br />

through which potential PMC contracts get reviewed. This licensing system only applies<br />

to those American firms doing business with the US Government. <strong>The</strong>re is also<br />

legislation that deals with the prosecution of contractors for crimes committed while<br />

serving abroad. Interestingly, the US uses the same legislation that governs the sale of<br />

military arms and services in terms of third parties abroad to regulate MPFs. This<br />

legislation is entitled the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which is a<br />

subset of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA). <strong>The</strong> ITAR was modified to deal with<br />

MPFs, specifically “the sale of ‘defence services’ or the sale of assistance, technical data<br />

or training related to military units.” 54 This legislation is administered through the<br />

Department of State. <strong>The</strong> legislation is the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act<br />

(MEJA), established in 2000. <strong>The</strong> act was not created to deal specifically with<br />

contractors, but with all civilians working with or for the US military in situations where<br />

the host nation was unable or unwilling to prosecute these people for crimes. However,<br />

the legislation was applied to contractors as the US generally negotiated immunity to<br />

local prosecution on behalf of Department of Defense for civilians in Status of Forces<br />

Agreements (SOFA) with host nations.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are several problems associated with this legislation. <strong>The</strong> first is that it<br />

originally only applied to contractors employed or working for the Department of<br />

Defense. This was later modified but some important US federal organizations are still<br />

excluded. It also took several years after the introduction of the legislation to establish<br />

implementing rules which would provide uniform guidance across all the US armed<br />

services as to who could arrest and detain civilian contractors. Next, the MEJA only<br />

applied to crimes that would garner one or more years of imprisonment, potentially<br />

resulting in contractors being excluded from discipline for misdemeanours, leading to the<br />

situation where military personnel are held accountable for misdemeanour offences, but<br />

not their civilian counterparts. Finally, prosecutors find that bringing extraterritorial cases<br />

to court is complex and expensive, which had lead to a dearth of such cases actually<br />

being pursued. 55 In summary, the US has some advanced domestic legislation related<br />

to the control of contractors on operations. It has leveraged and adapted existing<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Army</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Vol. 11.1 Spring 2008<br />

Combat Camera LF2008-0317d<br />

91

![La modularite dans l'Armee de terre canadienne [pdf 1.6 MB]](https://img.yumpu.com/17197737/1/188x260/la-modularite-dans-larmee-de-terre-canadienne-pdf-16-mb.jpg?quality=85)