Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Its original habitat on the mainland “included” Austrodanthonia, Austrostipa, Poa labillardieri and Themeda triandra <strong>grass</strong>lands<br />

and it requires dense ground cover for shelter, and open areas with relatively short <strong>grass</strong> in which to forage (Brown et al. 1991 p.<br />

150). Replacement <strong>of</strong> native <strong>grass</strong>es by exotic pasture <strong>grass</strong>es and weeds has reduced protective cover, but other factors<br />

including habitat destruction, predation by introduced vertebrates and exotic disease appear to be <strong>of</strong> much greater importance<br />

than weeds in its decline (Brown et al. 1991, Backhouse and Crossthwaite 2003). One important factor is probably soil<br />

compaction by bovid livestock (Brown 1987). It was last recorded in South <strong>Australia</strong> nearr Mt Gambier in 1890 (Aitken1983).<br />

Several colonies possibly still existed in the Victorian Western District in the late 1940s but it probably survived only in the<br />

Hamilton and Penshurst districts in the 1960s (Brown 1987). From c. 1971 the last remaining wild population on mainland<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> continued to exist in a highly modified environment “almost totallydominated by exotic plant species” at Hamilton<br />

rubbish tip, being able to escape predation by hiding in old car bodies and thickets <strong>of</strong> gorse Ulex europaeus L., and foraging in<br />

surrounding paddocks (Backhouse and Crossthwaite 2003 p. 3).<br />

Hadden (2002) surveyed 24 remnant <strong>grass</strong>land sites on the Victorian Western Volcanic Plains and Northern Plains by pitfall<br />

trapping and systematic and opportunistic searching from January 1995 to February 1996. She evaluated habitat by measuring<br />

cover <strong>of</strong> cool- and warm-season perennial <strong>grass</strong>es, native herbs, exotic <strong>grass</strong>es, exotic herbs, bare ground, dry litter, total floristic<br />

composition (native/exotic), sheep grazing pressure and invertebrate richness. Three mammal species were captured in c. 7500<br />

trap nights. Sminthopsis crassicaudata (Gould) was found at all sites in the Northern Plains and 7 <strong>of</strong> 12 sites in the Western<br />

Plains. One inidividual <strong>of</strong> the Common Dunnart S. murina (Waterhouse) was captured at a Western Plains site, the first Victorian<br />

<strong>grass</strong>land record. The introduced House Mouse Mus musculus L. was found at 5 <strong>of</strong> the Western Plains sites and 8 Northern<br />

Plains sites. Rabbits O. cuniculus and European Hare Lepus capensis were almost ubiquitous in Northern Plains sites but were<br />

observed at approximately half the Western Plains sites. No mammals were recorded at five <strong>of</strong> the Western Plains sites. S.<br />

crassicaudata was abundant at some floristically rich sites and also in degraded remnants and exotic pastures. It was relatively<br />

more abundant at sites that were lightly grazed, at sites with more open vegetation and floristically rich sites. It is an active<br />

hunter, mainly <strong>of</strong> invertebrates, and may require open areas for foraging, as well as tussock cover as a protection from predators.<br />

It was found living in rock piles and stone walls, and utilised wolf spider burrows on the Northern Plains. This species has<br />

disappeared from <strong>grass</strong>lands near Melbourne where it was once common. The almost ubiquitous M. musculus was relatively<br />

more abundant on heavily grazed sites, was absent from lightly grazed sites on the Western Plains, was more abundant at densely<br />

vegetated sites on the Western Plains and lightly vegetated sites on the Northern Plains, and was more common on floristically<br />

poor sites. Two other species, the introduced Brown Rat Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout) and native Swamp Rat R. lutreolus<br />

(Gray) have been recorded in Victorian <strong>grass</strong>lands in recent historical times.<br />

Mus musculus is a threat to some <strong>grass</strong>land plants. Mouse predation <strong>of</strong> tubers <strong>of</strong> Diuris fragrantissima is believed to have been<br />

responsible for mortality <strong>of</strong> perhaps 70% <strong>of</strong> plants at its single extant site during the mid-1980s (Webster et al. 2004).<br />

The Short-beaked Echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus (Shaw), occurs widely in <strong>grass</strong>lands (Menkhorst 1995c) but appears to be<br />

absent from most <strong>of</strong> the smaller remnants, particularly in areas <strong>of</strong> closer settlement.<br />

The highly depauperate mammalian faunas or remnant <strong>grass</strong>lands means that biodiversity components directly dependent upon<br />

mammalian activities are also threatened or lost. Obvious dependents include dung beetles (Scarabaeidae: Scarabaeinae and most<br />

Aphodiinae) that require a dung resource, and a range <strong>of</strong> ectoparasites (fleas, etc.) and endoparasites (Nematoda, etc.) that<br />

require their host for survival. The complex consequences <strong>of</strong> the loss <strong>of</strong> native grazing species and mammalian plant-predators<br />

have only recently begun to be explored and very little is known about the ramifications. However absence <strong>of</strong> soil disturbance by<br />

mammals has probably had a strong negative impact on regeneration <strong>of</strong> many native forbs (Reynolds 2005) and the dispersal<br />

opportunities for plant seeds must have been radically altered.<br />

Birds<br />

Few <strong>Australia</strong>n birds are restricted to <strong>grass</strong>lands and by necessity they are ground-nesting species. In New South Wales,<br />

populations <strong>of</strong> many <strong>grass</strong>land species that forage and nest on the ground have disappeared or shrunk to very low levels (Keith<br />

2004). In Victoria the most significant regions for threatened bird species include the Northern Plains and the Wimmera Plains,<br />

and few threatened species occur in the Western Volcanic Plains or the Gippsland Plains (Robinson 1991). Threatened birds in<br />

Victoria are more likely to be woodland or <strong>grass</strong>land species that are seed eaters or vertebrate predators, and to nest in tree<br />

hollows or on the ground (Robinson 1991). A number <strong>of</strong> species once common in native <strong>grass</strong>lands have declined markedly or<br />

disappeared from <strong>grass</strong>lands as the area <strong>of</strong> habitat has shrunk, however only two species that are more or less restricted to<br />

<strong>grass</strong>lands have endangered status (Table 16).<br />

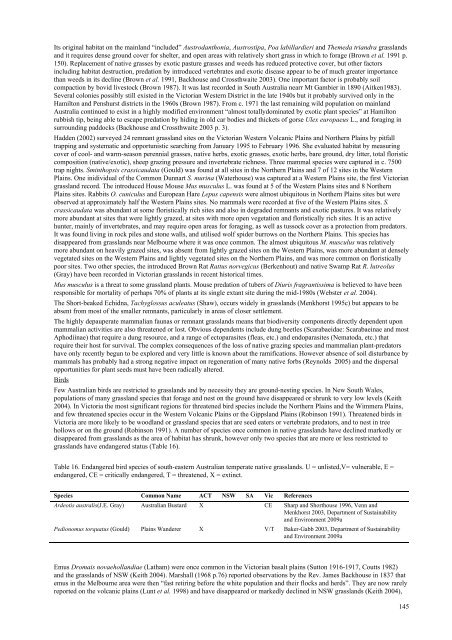

Table 16. Endangered bird species <strong>of</strong> south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong>n temperate native <strong>grass</strong>lands. U = unlisted,V= vulnerable, E =<br />

endangered, CE = critically endangered, T = threatened, X = extinct.<br />

Species Common Name ACT NSW SA Vic References<br />

Ardeotis australis(J.E. Gray) <strong>Australia</strong>n Bustard X CE Sharp and Shorthouse 1996, Venn and<br />

Menkhorst 2003, Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability<br />

and Environment 2009a<br />

Pedionomus torquatus (Gould) Plains Wanderer X V/T Baker-Gabb 2003, Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability<br />

and Environment 2009a<br />

Emus Dromais novaehollandiae (Latham) were once common in the Victorian basalt plains (Sutton 1916-1917, Coutts 1982)<br />

and the <strong>grass</strong>lands <strong>of</strong> NSW (Keith 2004). Marshall (1968 p.76) reported observations by the Rev. James Backhouse in 1837 that<br />

emus in the Melbourne area were then “fast retiring before the white population and their flocks and herds”. They are now rarely<br />

reported on the volcanic plains (Lunt et al. 1998) and have disappeared or markedly declined in NSW <strong>grass</strong>lands (Keith 2004),<br />

145