Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

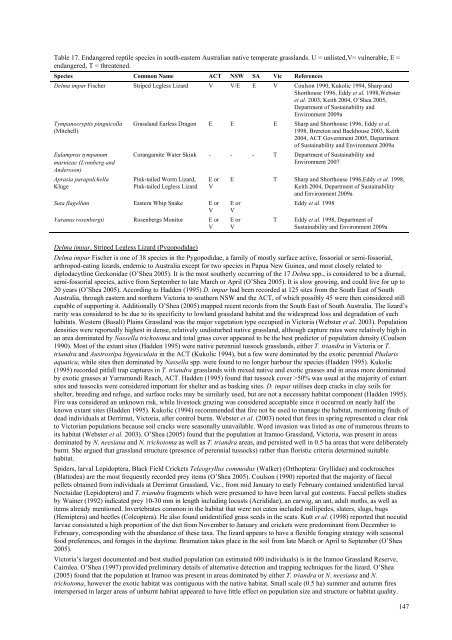

Table 17. Endangered reptile species in south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong>n native temperate <strong>grass</strong>lands. U = unlisted,V= vulnerable, E =<br />

endangered, T = threatened.<br />

Species Common Name ACT NSW SA Vic References<br />

Delma impar Fischer Striped Legless Lizard V V/E E V Coulson 1990, Kukolic 1994, Sharp and<br />

Shorthouse 1996, Eddy et al. 1998,Webster<br />

et al. 2003, Keith 2004, O’Shea 2005,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability and<br />

Environment 2009a<br />

Tympanocryptis pinguicolla<br />

(Mitchell)<br />

Eulamprus tympanum<br />

marnieae (Lvnnberg and<br />

Andersson)<br />

Aprasia parapulchella<br />

Kluge<br />

Grassland Earless Dragon E E E Sharp and Shorthouse 1996, Eddy et al.<br />

1998, Brereton and Backhouse 2003, Keith<br />

2004, ACT Government 2005, Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sustainability and Environment 2009a<br />

Corangamite Water Skink - - - T Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability and<br />

Environment 2007<br />

Pink-tailed Worm Lizard,<br />

Pink-tailed Legless Lizard<br />

E or<br />

V<br />

Suta flagellum Eastern Whip Snake E or<br />

V<br />

Varanus rosenbergii Rosenbergs Monitor E or<br />

V<br />

E T Sharp and Shorthouse 1996,Eddy et al. 1998,<br />

Keith 2004, Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability<br />

and Environment 2009a<br />

E or<br />

V<br />

E or<br />

V<br />

T<br />

Eddy et al. 1998<br />

Eddy et al. 1998, Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Sustainability and Environment 2009a<br />

Delma impar, Striped Legless Lizard (Pygopodidae)<br />

Delma impar Fischer is one <strong>of</strong> 38 species in the Pygopodidae, a family <strong>of</strong> mostly surface active, fossorial or semi-fossorial,<br />

arthropod-eating lizards, endemic to <strong>Australia</strong> except for two species in Papua New Guinea, and most closely related to<br />

diplodacytline Geckonidae (O’Shea 2005). It is the most southerly occurring <strong>of</strong> the 17 Delma spp., is considered to be a diurnal,<br />

semi-fossorial species, active from September to late March or April (O’Shea 2005). It is slow growing, and could live for up to<br />

20 years (O’Shea 2005). According to Hadden (1995) D. impar had been recorded at 125 sites from the South East <strong>of</strong> South<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>, through eastern and northern Victoria to southern NSW and the ACT, <strong>of</strong> which possibly 45 were then considered still<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> supporting it. Additionally O’Shea (2005) mapped recent records from the South East <strong>of</strong> South <strong>Australia</strong>. The lizard’s<br />

rarity was considered to be due to its specificity to lowland <strong>grass</strong>land habitat and the widespread loss and degradation <strong>of</strong> such<br />

habitats. Western (Basalt) Plains Grassland was the major vegetation type occupied in Victoria (Webster et al. 2003). Population<br />

densities were reportedly highest in dense, relatively undisturbed native <strong>grass</strong>land, although capture rates were relatively high in<br />

an area dominated by Nassella trichotoma and total <strong>grass</strong> cover appeared to be the best predictor <strong>of</strong> population density (Coulson<br />

1990). Most <strong>of</strong> the extant sites (Hadden 1995) were native perennial tussock <strong>grass</strong>lands, either T. triandra in Victoria or T.<br />

triandra and Austrostipa bigeniculata in the ACT (Kukolic 1994), but a few were dominated by the exotic perennial Phalaris<br />

aquatica, while sites then dominated by Nassella spp. were found to no longer harbour the species (Hadden 1995). Kukolic<br />

(1995) recorded pitfall trap captures in T. triandra <strong>grass</strong>lands with mixed native and exotic <strong>grass</strong>es and in areas more dominated<br />

by exotic <strong>grass</strong>es at Yarramundi Reach, ACT. Hadden (1995) found that tussock cover >50% was usual at the majority <strong>of</strong> extant<br />

sites and tussocks were considered important for shelter and as basking sites. D. impar utilises deep cracks in clay soils for<br />

shelter, breeding and refuge, and surface rocks may be similarly used, but are not a necessary habitat component (Hadden 1995).<br />

Fire was considered an unknown risk, while livestock grazing was considered acceptable since it occurred on nearly half the<br />

known extant sites (Hadden 1995). Kukolic (1994) recommended that fire not be used to manage the habitat, mentioning finds <strong>of</strong><br />

dead individuals at Derrimut, Victoria, after control burns. Webster et al. (2003) noted that fires in spring represented a clear risk<br />

to Victorian populations because soil cracks were seasonally unavailable. Weed invasion was listed as one <strong>of</strong> numerous threats to<br />

its habitat (Webster et al. 2003). O’Shea (2005) found that the population at Iramoo Grassland, Victoria, was present in areas<br />

dominated by N. neesiana and N. trichotoma as well as T. triandra areas, and persisted well in 0.5 ha areas that were deliberately<br />

burnt. She argued that <strong>grass</strong>land structure (presence <strong>of</strong> perennial tussocks) rather than floristic criteria determined suitable<br />

habitat.<br />

Spiders, larval Lepidoptera, Black Field Crickets Teleogryllus commodus (Walker) (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) and cockroaches<br />

(Blattodea) are the most frequently recorded prey items (O’Shea 2005). Coulson (1990) reported that the majority <strong>of</strong> faecal<br />

pellets obtained from individuals at Derrimut Grassland, Vic., from mid January to early February contained unidentified larval<br />

Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) and T. triandra fragments which were presumed to have been larval gut contents. Faecal pellets studies<br />

by Wainer (1992) indicated prey 10-30 mm in length including locusts (Acrididae), an earwig, an ant, adult moths, as well as<br />

items already mentioned. Invertebrates common in the habitat that were not eaten included millipedes, slaters, slugs, bugs<br />

(Hemiptera) and beetles (Coleoptera). He also found unidentified <strong>grass</strong> seeds in the scats. Kutt et al. (1998) reported that nocutid<br />

larvae consistuted a high proportion <strong>of</strong> the diet from November to January and crickets were predominant from December to<br />

February, corresponding with the abundance <strong>of</strong> these taxa. The lizard appears to have a flexible foraging strategy with seasonal<br />

food preferences, and forages in the daytime. Brumation takes place in the soil from late March or April to September (O’Shea<br />

2005).<br />

Victoria’s largest documented and best studied population (an estimated 600 individuals) is in the Iramoo Grassland Reserve,<br />

Cairnlea. O’Shea (1997) provided preliminary details <strong>of</strong> alternative detection and trapping techniques for the lizard. O’Shea<br />

(2005) found that the population at Iramoo was present in areas dominated by either T. triandra or N. neesiana and N.<br />

trichotoma, however the exotic habitat was contiguous with the native habitat. Small scale (0.5 ha) summer and autumn fires<br />

interspersed in larger areas <strong>of</strong> unburnt habitat appeared to have little effect on population size and structure or habitat quality.<br />

147