Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European ...

Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European ...

Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

106 <strong>Twenty</strong>-<strong>First</strong> <strong>Century</strong> <strong>Populism</strong><br />

Sonderfall, the alleged uniqueness, isolation, prosperity and neutrality <strong>of</strong><br />

Switzerland, coupled with a stance vis á vis the EU and other international<br />

institutions and associations that closely resembles that <strong>of</strong> AUNS. Finally<br />

comes a marked conservatism in social affairs (i.e. law-and-order rhetoric),<br />

alongside the fight for tax cuts and public expenditure reductions (see Betz,<br />

2005).<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> its ideology, therefore, the SVP/UDC closely resembles other<br />

right-wing populist formations covered in this volume. Like them, the party<br />

embodies some <strong>of</strong> contemporary Europe’s most blatant contradictions:<br />

between hyper-modernism on the one hand, and the desire to protect native<br />

‘traditional’ cultures on the other; between the perceived need for immigrant<br />

labour on the one hand, and the schizophrenic desire not to see and<br />

have to deal with foreigners on the other (as the party’s slogan says: ‘yes to<br />

foreign workers, no to immigrants’). <strong>The</strong> only aspect that partially differentiates<br />

the SVP/UDC from the ‘ideal type’ <strong>of</strong> populist party defined in the<br />

introduction to this volume is that, despite Blocher having gained a great<br />

reputation within its ranks as leader <strong>of</strong> the radicalization process, he remains<br />

just one <strong>of</strong> the party’s leaders. Moreover, there are still two different visions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the party’s future battling against each other (with the Bernese branch<br />

more moderate and conservative than the now hegemonic Zurich branch).<br />

Unlike Forza Italia in Italy, therefore, the SVP/UDC has never been purely<br />

and simply ‘a personal party’ (Calise, 2000).<br />

<strong>The</strong> radicalization process has paid dividends in electoral terms, with the<br />

party nearly doubling its national vote share in about ten years, following<br />

sweeping successes in cantonal parliaments. This happened first at the<br />

expense <strong>of</strong> extreme formations such as the Swiss Democrats, and then other<br />

‘bourgeois’ parties (FDP/PRD and CVP/PDC), while the Social Democrats<br />

(SPS/PSS) and the Greens have also benefited from a climate <strong>of</strong> increasing<br />

polarization − almost in the style <strong>of</strong> adversarial democracies. This is an interesting<br />

process in a country where the Left has traditionally been weak. 6<br />

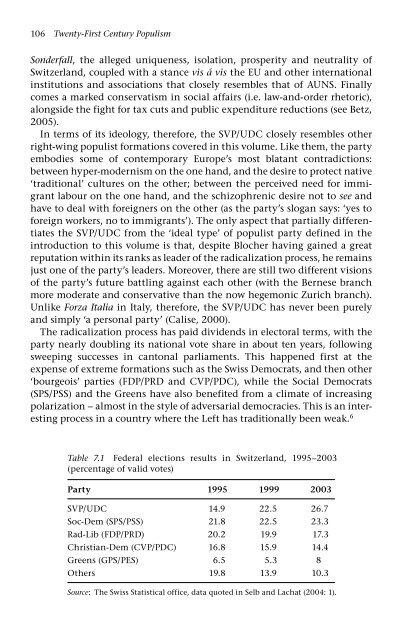

Table 7.1 Federal elections results in Switzerland, 1995–2003<br />

(percentage <strong>of</strong> valid votes)<br />

Party 1995 1999 2003<br />

SVP/UDC 14.9 22.5 26.7<br />

Soc-Dem (SPS/PSS) 21.8 22.5 23.3<br />

Rad-Lib (FDP/PRD) 20.2 19.9 17.3<br />

Christian-Dem (CVP/PDC) 16.8 15.9 14.4<br />

Greens (GPS/PES) 6.5 5.3 8<br />

Others 19.8 13.9 10.3<br />

Source: <strong>The</strong> Swiss Statistical <strong>of</strong>fice, data quoted in Selb and Lachat (2004: 1).