Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European ...

Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European ...

Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

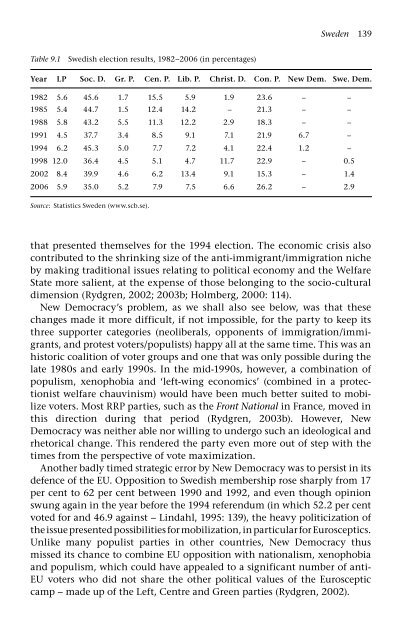

Table 9.1 Swedish election results, 1982−2006 (in percentages)<br />

Sweden 139<br />

Year LP Soc. D. Gr. P. Cen. P. Lib. P. Christ. D. Con. P. New Dem. Swe. Dem.<br />

1982 5.6 45.6 1.7 15.5 5.9 1.9 23.6 – –<br />

1985 5.4 44.7 1.5 12.4 14.2 – 21.3 – –<br />

1988 5.8 43.2 5.5 11.3 12.2 2.9 18.3 – –<br />

1991 4.5 37.7 3.4 8.5 9.1 7.1 21.9 6.7 –<br />

1994 6.2 45.3 5.0 7.7 7.2 4.1 22.4 1.2 –<br />

1998 12.0 36.4 4.5 5.1 4.7 11.7 22.9 – 0.5<br />

2002 8.4 39.9 4.6 6.2 13.4 9.1 15.3 – 1.4<br />

2006 5.9 35.0 5.2 7.9 7.5 6.6 26.2 – 2.9<br />

Source: Statistics Sweden (www.scb.se).<br />

that presented themselves for the 1994 election. <strong>The</strong> economic crisis also<br />

contributed to the shrinking size <strong>of</strong> the anti-immigrant/immigration niche<br />

by making traditional issues relating to political economy and the Welfare<br />

State more salient, at the expense <strong>of</strong> those belonging to the socio-cultural<br />

dimension (Rydgren, 2002; 2003b; Holmberg, 2000: 114).<br />

New Democracy’s problem, as we shall also see below, was that these<br />

changes made it more difficult, if not impossible, for the party to keep its<br />

three supporter categories (neoliberals, opponents <strong>of</strong> immigration/immigrants,<br />

and protest voters/populists) happy all at the same time. This was an<br />

historic coalition <strong>of</strong> voter groups and one that was only possible during the<br />

late 1980s and early 1990s. In the mid-1990s, however, a combination <strong>of</strong><br />

populism, xenophobia and ‘left-wing economics’ (combined in a protectionist<br />

welfare chauvinism) would have been much better suited to mobilize<br />

voters. Most RRP parties, such as the Front National in France, moved in<br />

this direction during that period (Rydgren, 2003b). However, New<br />

Democracy was neither able nor willing to undergo such an ideological and<br />

rhetorical change. This rendered the party even more out <strong>of</strong> step with the<br />

times from the perspective <strong>of</strong> vote maximization.<br />

Another badly timed strategic error by New Democracy was to persist in its<br />

defence <strong>of</strong> the EU. Opposition to Swedish membership rose sharply from 17<br />

per cent to 62 per cent between 1990 and 1992, and even though opinion<br />

swung again in the year before the 1994 referendum (in which 52.2 per cent<br />

voted for and 46.9 against − Lindahl, 1995: 139), the heavy politicization <strong>of</strong><br />

the issue presented possibilities for mobilization, in particular for Eurosceptics.<br />

Unlike many populist parties in other countries, New Democracy thus<br />

missed its chance to combine EU opposition with nationalism, xenophobia<br />

and populism, which could have appealed to a significant number <strong>of</strong> anti-<br />

EU voters who did not share the other political values <strong>of</strong> the Eurosceptic<br />

camp − made up <strong>of</strong> the Left, Centre and Green parties (Rydgren, 2002).