Natural Science in Archaeology

Natural Science in Archaeology

Natural Science in Archaeology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

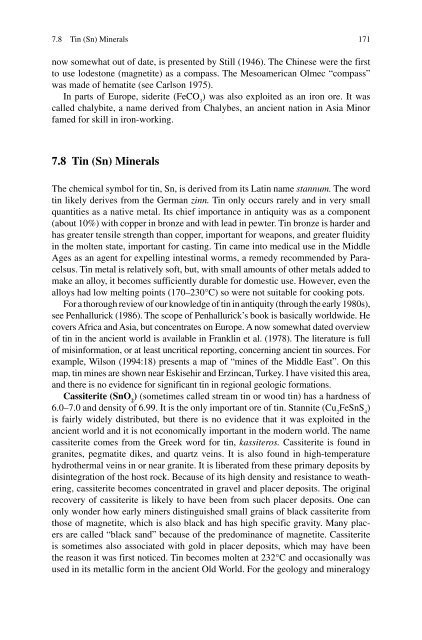

7.8 T<strong>in</strong> (Sn) M<strong>in</strong>erals 171<br />

now somewhat out of date, is presented by Still (1946). The Ch<strong>in</strong>ese were the first<br />

to use lodestone (magnetite) as a compass. The Mesoamerican Olmec “compass”<br />

was made of hematite (see Carlson 1975).<br />

In parts of Europe, siderite (FeCO 3 ) was also exploited as an iron ore. It was<br />

called chalybite, a name derived from Chalybes, an ancient nation <strong>in</strong> Asia M<strong>in</strong>or<br />

famed for skill <strong>in</strong> iron-work<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

7.8 T<strong>in</strong> (Sn) M<strong>in</strong>erals<br />

The chemical symbol for t<strong>in</strong>, Sn, is derived from its Lat<strong>in</strong> name stannum. The word<br />

t<strong>in</strong> likely derives from the German z<strong>in</strong>n. T<strong>in</strong> only occurs rarely and <strong>in</strong> very small<br />

quantities as a native metal. Its chief importance <strong>in</strong> antiquity was as a component<br />

(about 10%) with copper <strong>in</strong> bronze and with lead <strong>in</strong> pewter. T<strong>in</strong> bronze is harder and<br />

has greater tensile strength than copper, important for weapons, and greater fluidity<br />

<strong>in</strong> the molten state, important for cast<strong>in</strong>g. T<strong>in</strong> came <strong>in</strong>to medical use <strong>in</strong> the Middle<br />

Ages as an agent for expell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al worms, a remedy recommended by Paracelsus.<br />

T<strong>in</strong> metal is relatively soft, but, with small amounts of other metals added to<br />

make an alloy, it becomes sufficiently durable for domestic use. However, even the<br />

alloys had low melt<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts (170–230°C) so were not suitable for cook<strong>in</strong>g pots.<br />

For a thorough review of our knowledge of t<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> antiquity (through the early 1980s),<br />

see Penhallurick (1986). The scope of Penhallurick’s book is basically worldwide. He<br />

covers Africa and Asia, but concentrates on Europe. A now somewhat dated overview<br />

of t<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the ancient world is available <strong>in</strong> Frankl<strong>in</strong> et al. (1978). The literature is full<br />

of mis<strong>in</strong>formation, or at least uncritical report<strong>in</strong>g, concern<strong>in</strong>g ancient t<strong>in</strong> sources. For<br />

example, Wilson (1994:18) presents a map of “m<strong>in</strong>es of the Middle East”. On this<br />

map, t<strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>es are shown near Eskisehir and Erz<strong>in</strong>can, Turkey. I have visited this area,<br />

and there is no evidence for significant t<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> regional geologic formations.<br />

Cassiterite (SnO 2 ) (sometimes called stream t<strong>in</strong> or wood t<strong>in</strong>) has a hardness of<br />

6.0–7.0 and density of 6.99. It is the only important ore of t<strong>in</strong>. Stannite (Cu 2 FeSnS 4 )<br />

is fairly widely distributed, but there is no evidence that it was exploited <strong>in</strong> the<br />

ancient world and it is not economically important <strong>in</strong> the modern world. The name<br />

cassiterite comes from the Greek word for t<strong>in</strong>, kassiteros. Cassiterite is found <strong>in</strong><br />

granites, pegmatite dikes, and quartz ve<strong>in</strong>s. It is also found <strong>in</strong> high-temperature<br />

hydrothermal ve<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> or near granite. It is liberated from these primary deposits by<br />

dis<strong>in</strong>tegration of the host rock. Because of its high density and resistance to weather<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

cassiterite becomes concentrated <strong>in</strong> gravel and placer deposits. The orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

recovery of cassiterite is likely to have been from such placer deposits. One can<br />

only wonder how early m<strong>in</strong>ers dist<strong>in</strong>guished small gra<strong>in</strong>s of black cassiterite from<br />

those of magnetite, which is also black and has high specific gravity. Many placers<br />

are called “black sand” because of the predom<strong>in</strong>ance of magnetite. Cassiterite<br />

is sometimes also associated with gold <strong>in</strong> placer deposits, which may have been<br />

the reason it was first noticed. T<strong>in</strong> becomes molten at 232°C and occasionally was<br />

used <strong>in</strong> its metallic form <strong>in</strong> the ancient Old World. For the geology and m<strong>in</strong>eralogy