6th European Conference - Academic Conferences

6th European Conference - Academic Conferences

6th European Conference - Academic Conferences

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

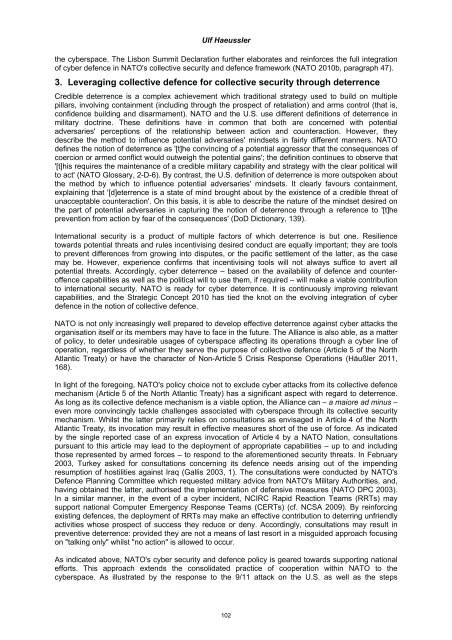

Ulf Haeussler<br />

the cyberspace. The Lisbon Summit Declaration further elaborates and reinforces the full integration<br />

of cyber defence in NATO's collective security and defence framework (NATO 2010b, paragraph 47).<br />

3. Leveraging collective defence for collective security through deterrence<br />

Credible deterrence is a complex achievement which traditional strategy used to build on multiple<br />

pillars, involving containment (including through the prospect of retaliation) and arms control (that is,<br />

confidence building and disarmament). NATO and the U.S. use different definitions of deterrence in<br />

military doctrine. These definitions have in common that both are concerned with potential<br />

adversaries' perceptions of the relationship between action and counteraction. However, they<br />

describe the method to influence potential adversaries' mindsets in fairly different manners. NATO<br />

defines the notion of deterrence as '[t]he convincing of a potential aggressor that the consequences of<br />

coercion or armed conflict would outweigh the potential gains'; the definition continues to observe that<br />

'[t]his requires the maintenance of a credible military capability and strategy with the clear political will<br />

to act' (NATO Glossary, 2-D-6). By contrast, the U.S. definition of deterrence is more outspoken about<br />

the method by which to influence potential adversaries' mindsets. It clearly favours containment,<br />

explaining that '[d]eterrence is a state of mind brought about by the existence of a credible threat of<br />

unacceptable counteraction'. On this basis, it is able to describe the nature of the mindset desired on<br />

the part of potential adversaries in capturing the notion of deterrence through a reference to '[t]he<br />

prevention from action by fear of the consequences' (DoD Dictionary, 139).<br />

International security is a product of multiple factors of which deterrence is but one. Resilience<br />

towards potential threats and rules incentivising desired conduct are equally important; they are tools<br />

to prevent differences from growing into disputes, or the pacific settlement of the latter, as the case<br />

may be. However, experience confirms that incentivising tools will not always suffice to avert all<br />

potential threats. Accordingly, cyber deterrence – based on the availability of defence and counteroffence<br />

capabilities as well as the political will to use them, if required – will make a viable contribution<br />

to international security. NATO is ready for cyber deterrence. It is continuously improving relevant<br />

capabilities, and the Strategic Concept 2010 has tied the knot on the evolving integration of cyber<br />

defence in the notion of collective defence.<br />

NATO is not only increasingly well prepared to develop effective deterrence against cyber attacks the<br />

organisation itself or its members may have to face in the future. The Alliance is also able, as a matter<br />

of policy, to deter undesirable usages of cyberspace affecting its operations through a cyber line of<br />

operation, regardless of whether they serve the purpose of collective defence (Article 5 of the North<br />

Atlantic Treaty) or have the character of Non-Article 5 Crisis Response Operations (Häußler 2011,<br />

168).<br />

In light of the foregoing, NATO's policy choice not to exclude cyber attacks from its collective defence<br />

mechanism (Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty) has a significant aspect with regard to deterrence.<br />

As long as its collective defence mechanism is a viable option, the Alliance can – a maiore ad minus –<br />

even more convincingly tackle challenges associated with cyberspace through its collective security<br />

mechanism. Whilst the latter primarily relies on consultations as envisaged in Article 4 of the North<br />

Atlantic Treaty, its invocation may result in effective measures short of the use of force. As indicated<br />

by the single reported case of an express invocation of Article 4 by a NATO Nation, consultations<br />

pursuant to this article may lead to the deployment of appropriate capabilities – up to and including<br />

those represented by armed forces – to respond to the aforementioned security threats. In February<br />

2003, Turkey asked for consultations concerning its defence needs arising out of the impending<br />

resumption of hostilities against Iraq (Gallis 2003, 1). The consultations were conducted by NATO's<br />

Defence Planning Committee which requested military advice from NATO's Military Authorities, and,<br />

having obtained the latter, authorised the implementation of defensive measures (NATO DPC 2003).<br />

In a similar manner, in the event of a cyber incident, NCIRC Rapid Reaction Teams (RRTs) may<br />

support national Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) (cf. NCSA 2009). By reinforcing<br />

existing defences, the deployment of RRTs may make an effective contribution to deterring unfriendly<br />

activities whose prospect of success they reduce or deny. Accordingly, consultations may result in<br />

preventive deterrence: provided they are not a means of last resort in a misguided approach focusing<br />

on "talking only" whilst "no action" is allowed to occur.<br />

As indicated above, NATO's cyber security and defence policy is geared towards supporting national<br />

efforts. This approach extends the consolidated practice of cooperation within NATO to the<br />

cyberspace. As illustrated by the response to the 9/11 attack on the U.S. as well as the steps<br />

102