Namibia PDNA 2009 - GFDRR

Namibia PDNA 2009 - GFDRR

Namibia PDNA 2009 - GFDRR

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The major long-term environmental challenges for <strong>Namibia</strong> will<br />

be posed by rapid population growth and climate change. Due<br />

to the relatively light development pressures to date, much<br />

remains to be done to strengthen systems for environmental<br />

impact assessment and mitigation, currently well-established<br />

only for large mining operations. There have been active<br />

successes for environmental management, however, such as<br />

the rapid development of the national CBNRM approach, and<br />

increases in numbers of large wildlife throughout much of the<br />

country.<br />

Damage and Losses Assessment<br />

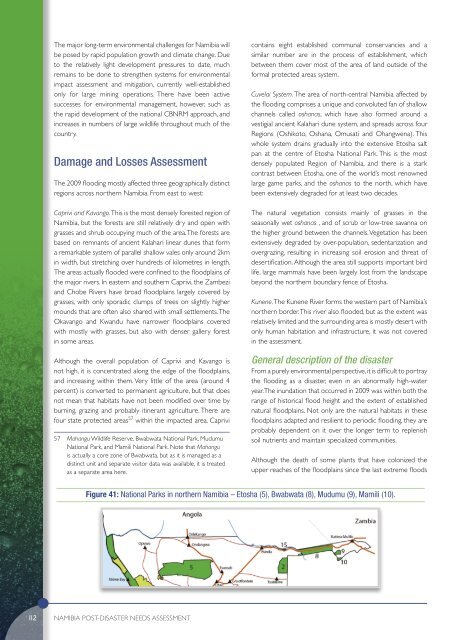

The <strong>2009</strong> flooding mostly affected three geographically distinct<br />

regions across northern <strong>Namibia</strong>. From east to west:<br />

Caprivi and Kavango. This is the most densely forested region of<br />

<strong>Namibia</strong>, but the forests are still relatively dry and open with<br />

grasses and shrub occupying much of the area. The forests are<br />

based on remnants of ancient Kalahari linear dunes that form<br />

a remarkable system of parallel shallow vales only around 2km<br />

in width, but stretching over hundreds of kilometres in length.<br />

The areas actually flooded were confined to the floodplains of<br />

the major rivers. In eastern and southern Caprivi, the Zambezi<br />

and Chobe Rivers have broad floodplains largely covered by<br />

grasses, with only sporadic clumps of trees on slightly higher<br />

mounds that are often also shared with small settlements. The<br />

Okavango and Kwandu have narrower floodplains covered<br />

with mostly with grasses, but also with denser gallery forest<br />

in some areas.<br />

Although the overall population of Caprivi and Kavango is<br />

not high, it is concentrated along the edge of the floodplains,<br />

and increasing within them. Very little of the area (around 4<br />

percent) is converted to permanent agriculture, but that does<br />

not mean that habitats have not been modified over time by<br />

burning, grazing and probably itinerant agriculture. There are<br />

four state protected areas 57 within the impacted area. Caprivi<br />

57 Mahangu Wildlife Reserve, Bwabwata National Park, Mudumu<br />

National Park, and Mamili National Park. Note that Mahangu<br />

is actually a core zone of Bwabwata, but as it is managed as a<br />

distinct unit and separate visitor data was available, it is treated<br />

as a separate area here.<br />

contains eight established communal conservancies and a<br />

similar number are in the process of establishment, which<br />

between them cover most of the area of land outside of the<br />

formal protected areas system.<br />

Cuvelai System. The area of north-central <strong>Namibia</strong> affected by<br />

the flooding comprises a unique and convoluted fan of shallow<br />

channels called oshanas, which have also formed around a<br />

vestigial ancient Kalahari dune system, and spreads across four<br />

Regions (Oshikoto, Oshana, Omusati and Ohangwena). This<br />

whole system drains gradually into the extensive Etosha salt<br />

pan at the centre of Etosha National Park. This is the most<br />

densely populated Region of <strong>Namibia</strong>, and there is a stark<br />

contrast between Etosha, one of the world’s most renowned<br />

large game parks, and the oshanas to the north, which have<br />

been extensively degraded for at least two decades.<br />

The natural vegetation consists mainly of grasses in the<br />

seasonally wet oshanas , and of scrub or low-tree savanna on<br />

the higher ground between the channels. Vegetation has been<br />

extensively degraded by over-population, sedentarization and<br />

overgrazing, resulting in increasing soil erosion and threat of<br />

desertification. Although the area still supports important bird<br />

life, large mammals have been largely lost from the landscape<br />

beyond the northern boundary fence of Etosha.<br />

Kunene. The Kunene River forms the western part of <strong>Namibia</strong>’s<br />

northern border. This river also flooded, but as the extent was<br />

relatively limited and the surrounding area is mostly desert with<br />

only human habitation and infrastructure, it was not covered<br />

in the assessment.<br />

General description of the disaster<br />

From a purely environmental perspective, it is difficult to portray<br />

the flooding as a disaster, even in an abnormally high-water<br />

year. The inundation that occurred in <strong>2009</strong> was within both the<br />

range of historical flood height and the extent of established<br />

natural floodplains. Not only are the natural habitats in these<br />

floodplains adapted and resilient to periodic flooding, they are<br />

probably dependent on it over the longer term to replenish<br />

soil nutrients and maintain specialized communities.<br />

Although the death of some plants that have colonized the<br />

upper reaches of the floodplains since the last extreme floods<br />

Figure 41: National Parks in northern <strong>Namibia</strong> – Etosha (5), Bwabwata (8), Mudumu (9), Mamili (10).<br />

112<br />

<strong>Namibia</strong> POST-DISASTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT