Educational Research - the Ethics and Aesthetics of Statistics

Educational Research - the Ethics and Aesthetics of Statistics

Educational Research - the Ethics and Aesthetics of Statistics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

210 P. St<strong>and</strong>ish<br />

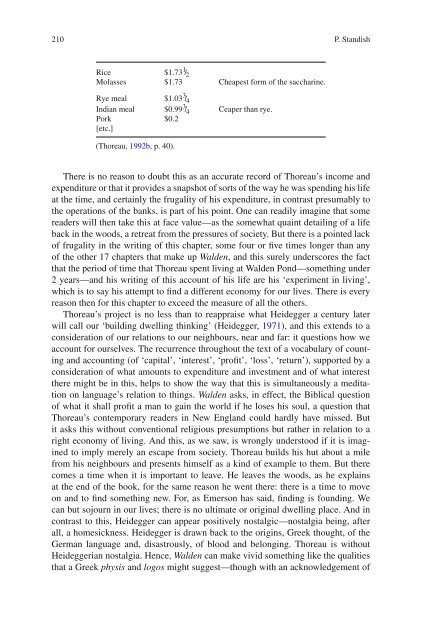

Rice $1.73 1 / 2<br />

Molasses $1.73 Cheapest form <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> saccharine.<br />

Rye meal $1.03 3 / 4<br />

Indian meal $0.99 3 / 4 Ceaper than rye.<br />

Pork $0.2<br />

[etc.]<br />

(Thoreau, 1992b, p. 40).<br />

There is no reason to doubt this as an accurate record <strong>of</strong> Thoreau’s income <strong>and</strong><br />

expenditure or that it provides a snapshot <strong>of</strong> sorts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> way he was spending his life<br />

at <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>and</strong> certainly <strong>the</strong> frugality <strong>of</strong> his expenditure, in contrast presumably to<br />

<strong>the</strong> operations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> banks, is part <strong>of</strong> his point. One can readily imagine that some<br />

readers will <strong>the</strong>n take this at face value—as <strong>the</strong> somewhat quaint detailing <strong>of</strong> a life<br />

back in <strong>the</strong> woods, a retreat from <strong>the</strong> pressures <strong>of</strong> society. But <strong>the</strong>re is a pointed lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> frugality in <strong>the</strong> writing <strong>of</strong> this chapter, some four or five times longer than any<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r 17 chapters that make up Walden, <strong>and</strong> this surely underscores <strong>the</strong> fact<br />

that <strong>the</strong> period <strong>of</strong> time that Thoreau spent living at Walden Pond—something under<br />

2 years—<strong>and</strong> his writing <strong>of</strong> this account <strong>of</strong> his life are his ‘experiment in living’,<br />

which is to say his attempt to find a different economy for our lives. There is every<br />

reason <strong>the</strong>n for this chapter to exceed <strong>the</strong> measure <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

Thoreau’s project is no less than to reappraise what Heidegger a century later<br />

will call our ‘building dwelling thinking’ (Heidegger, 1971), <strong>and</strong> this extends to a<br />

consideration <strong>of</strong> our relations to our neighbours, near <strong>and</strong> far: it questions how we<br />

account for ourselves. The recurrence throughout <strong>the</strong> text <strong>of</strong> a vocabulary <strong>of</strong> counting<br />

<strong>and</strong> accounting (<strong>of</strong> ‘capital’, ‘interest’, ‘pr<strong>of</strong>it’, ‘loss’, ‘return’), supported by a<br />

consideration <strong>of</strong> what amounts to expenditure <strong>and</strong> investment <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> what interest<br />

<strong>the</strong>re might be in this, helps to show <strong>the</strong> way that this is simultaneously a meditation<br />

on language’s relation to things. Walden asks, in effect, <strong>the</strong> Biblical question<br />

<strong>of</strong> what it shall pr<strong>of</strong>it a man to gain <strong>the</strong> world if he loses his soul, a question that<br />

Thoreau’s contemporary readers in New Engl<strong>and</strong> could hardly have missed. But<br />

it asks this without conventional religious presumptions but ra<strong>the</strong>r in relation to a<br />

right economy <strong>of</strong> living. And this, as we saw, is wrongly understood if it is imagined<br />

to imply merely an escape from society. Thoreau builds his hut about a mile<br />

from his neighbours <strong>and</strong> presents himself as a kind <strong>of</strong> example to <strong>the</strong>m. But <strong>the</strong>re<br />

comes a time when it is important to leave. He leaves <strong>the</strong> woods, as he explains<br />

at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> book, for <strong>the</strong> same reason he went <strong>the</strong>re: <strong>the</strong>re is a time to move<br />

on <strong>and</strong> to find something new. For, as Emerson has said, finding is founding. We<br />

can but sojourn in our lives; <strong>the</strong>re is no ultimate or original dwelling place. And in<br />

contrast to this, Heidegger can appear positively nostalgic—nostalgia being, after<br />

all, a homesickness. Heidegger is drawn back to <strong>the</strong> origins, Greek thought, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

German language <strong>and</strong>, disastrously, <strong>of</strong> blood <strong>and</strong> belonging. Thoreau is without<br />

Heideggerian nostalgia. Hence, Walden can make vivid something like <strong>the</strong> qualities<br />

that a Greek physis <strong>and</strong> logos might suggest—though with an acknowledgement <strong>of</strong>