learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

LSRC reference Section 7<br />

page 110/111<br />

7.3<br />

Sternberg’s theory of thinking <strong>styles</strong> and his<br />

Thinking Styles Inventory (TSI)<br />

Introduction<br />

Robert Sternberg is a major figure in cognitive<br />

psychology; he is IBM professor of psychology and<br />

education at Yale University and was president<br />

of the American Psychological Association in 2003/04.<br />

His theory of mental self-government and model<br />

of thinking <strong>styles</strong> (1999) are becoming well known<br />

and are highly developed into functions, forms, levels,<br />

scope and leanings. He deals explicitly with the<br />

relationship between thinking <strong>styles</strong> and methods<br />

of instruction, as well as the relationship between<br />

thinking <strong>styles</strong> and methods of assessment. He also<br />

makes major claims for improving student performance<br />

via improved pedagogy.<br />

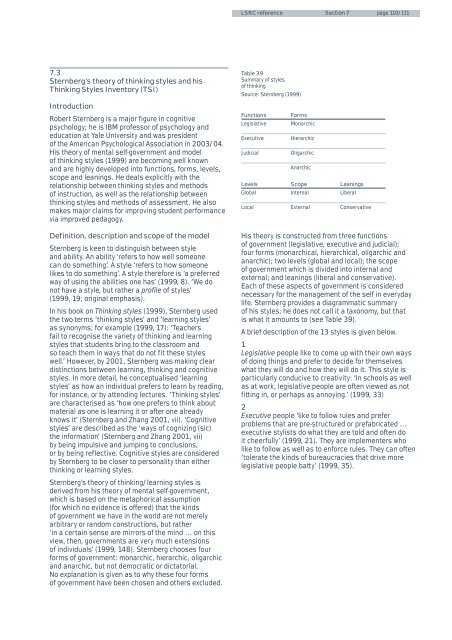

Table 39<br />

Summary of <strong>styles</strong><br />

of thinking<br />

Source: Sternberg (1999)<br />

Functions<br />

Legislative<br />

Executive<br />

Judicial<br />

Levels<br />

Global<br />

Local<br />

Forms<br />

Monarchic<br />

Hierarchic<br />

Oligarchic<br />

Anarchic<br />

Scope<br />

Internal<br />

External<br />

Leanings<br />

Liberal<br />

Conservative<br />

Definition, description and scope of the model<br />

Sternberg is keen to distinguish between style<br />

and ability. An ability ‘refers to how well someone<br />

can do something’. A style ‘refers to how someone<br />

likes to do something’. A style therefore is ‘a preferred<br />

way of using the abilities one has’ (1999, 8). ‘We do<br />

not have a style, but rather a profile of <strong>styles</strong>’<br />

(1999, 19; original emphasis).<br />

In his book on Thinking <strong>styles</strong> (1999), Sternberg used<br />

the two terms ‘thinking <strong>styles</strong>’ and ‘<strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong>’<br />

as synonyms; for example (1999, 17): ‘Teachers<br />

fail to recognise the variety of thinking and <strong>learning</strong><br />

<strong>styles</strong> that students bring to the classroom and<br />

so teach them in ways that do not fit these <strong>styles</strong><br />

well.’ However, by 2001, Sternberg was making clear<br />

distinctions between <strong>learning</strong>, thinking and cognitive<br />

<strong>styles</strong>. In more detail, he conceptualised ‘<strong>learning</strong><br />

<strong>styles</strong>’ as how an individual prefers to learn by reading,<br />

for instance, or by attending lectures. ‘Thinking <strong>styles</strong>’<br />

are characterised as ‘how one prefers to think about<br />

material as one is <strong>learning</strong> it or after one already<br />

knows it’ (Sternberg and Zhang 2001, vii). ‘Cognitive<br />

<strong>styles</strong>’ are described as the ‘ways of cognizing (sic)<br />

the information’ (Sternberg and Zhang 2001, vii)<br />

by being impulsive and jumping to conclusions,<br />

or by being reflective. Cognitive <strong>styles</strong> are considered<br />

by Sternberg to be closer to personality than either<br />

thinking or <strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong>.<br />

Sternberg’s theory of thinking/<strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong> is<br />

derived from his theory of mental self-government,<br />

which is based on the metaphorical assumption<br />

(for which no evidence is offered) that the kinds<br />

of government we have in the world are not merely<br />

arbitrary or random constructions, but rather<br />

‘in a certain sense are mirrors of the mind … on this<br />

view, then, governments are very much extensions<br />

of individuals’ (1999, 148). Sternberg chooses four<br />

forms of government: monarchic, hierarchic, oligarchic<br />

and anarchic, but not democratic or dictatorial.<br />

No explanation is given as to why these four forms<br />

of government have been chosen and others excluded.<br />

His theory is constructed from three functions<br />

of government (legislative, executive and judicial);<br />

four forms (monarchical, hierarchical, oligarchic and<br />

anarchic); two levels (global and local); the scope<br />

of government which is divided into internal and<br />

external; and leanings (liberal and conservative).<br />

Each of these aspects of government is considered<br />

necessary for the management of the self in everyday<br />

life. Sternberg provides a diagrammatic summary<br />

of his <strong>styles</strong>; he does not call it a taxonomy, but that<br />

is what it amounts to (see Table 39).<br />

A brief description of the 13 <strong>styles</strong> is given below.<br />

1<br />

Legislative people like to come up with their own ways<br />

of doing things and prefer to decide for themselves<br />

what they will do and how they will do it. This style is<br />

particularly conducive to creativity: ‘In schools as well<br />

as at work, legislative people are often viewed as not<br />

fitting in, or perhaps as annoying.’ (1999, 33)<br />

2<br />

Executive people ‘like to follow rules and prefer<br />

problems that are pre-structured or prefabricated …<br />

executive stylists do what they are told and often do<br />

it cheerfully’ (1999, 21). They are implementers who<br />

like to follow as well as to enforce rules. They can often<br />

‘tolerate the kinds of bureaucracies that drive more<br />

legislative people batty’ (1999, 35).