learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Riding and Rayner (1998) do not define <strong>learning</strong> style,<br />

but group models of <strong>learning</strong> style in terms of their<br />

emphasis on:<br />

experiential <strong>learning</strong><br />

orientation to study<br />

instructional preference<br />

the development of cognitive skills and<br />

<strong>learning</strong> strategies.<br />

They state that their own model is directed primarily<br />

at how cognitive skills develop, and claim that it<br />

has implications for orientation to study, instructional<br />

preference and experiential <strong>learning</strong>, as well as for<br />

social behaviour and managerial performance.<br />

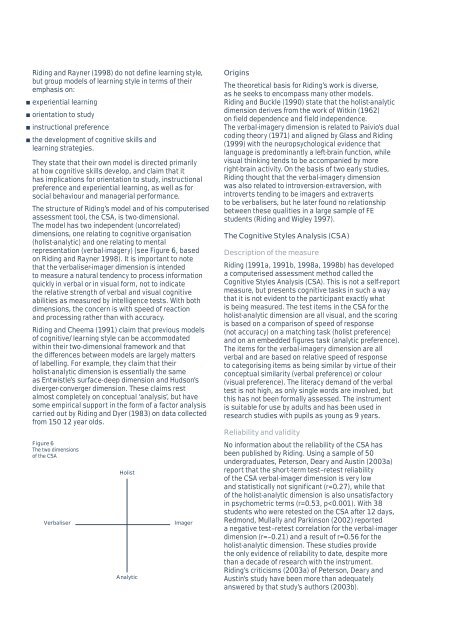

The structure of Riding’s model and of his computerised<br />

assessment tool, the CSA, is two-dimensional.<br />

The model has two independent (uncorrelated)<br />

dimensions, one relating to cognitive organisation<br />

(holist-analytic) and one relating to mental<br />

representation (verbal-imagery) (see Figure 6, based<br />

on Riding and Rayner 1998). It is important to note<br />

that the verbaliser-imager dimension is intended<br />

to measure a natural tendency to process information<br />

quickly in verbal or in visual form, not to indicate<br />

the relative strength of verbal and visual cognitive<br />

abilities as measured by intelligence tests. With both<br />

dimensions, the concern is with speed of reaction<br />

and processing rather than with accuracy.<br />

Riding and Cheema (1991) claim that previous models<br />

of cognitive/<strong>learning</strong> style can be accommodated<br />

within their two-dimensional framework and that<br />

the differences between models are largely matters<br />

of labelling. For example, they claim that their<br />

holist-analytic dimension is essentially the same<br />

as Entwistle’s surface-deep dimension and Hudson’s<br />

diverger-converger dimension. These claims rest<br />

almost completely on conceptual ‘analysis’, but have<br />

some empirical support in the form of a factor analysis<br />

carried out by Riding and Dyer (1983) on data collected<br />

from 150 12 year olds.<br />

Figure 6<br />

The two dimensions<br />

of the CSA<br />

Verbaliser<br />

Holist<br />

Analytic<br />

Imager<br />

Origins<br />

The theoretical basis for Riding’s work is diverse,<br />

as he seeks to encompass many other models.<br />

Riding and Buckle (1990) state that the holist-analytic<br />

dimension derives from the work of Witkin (1962)<br />

on field dependence and field independence.<br />

The verbal-imagery dimension is related to Paivio’s dual<br />

coding theory (1971) and aligned by Glass and Riding<br />

(1999) with the neuropsychological evidence that<br />

language is predominantly a left-brain function, while<br />

visual thinking tends to be accompanied by more<br />

right-brain activity. On the basis of two early studies,<br />

Riding thought that the verbal-imagery dimension<br />

was also related to introversion-extraversion, with<br />

introverts tending to be imagers and extraverts<br />

to be verbalisers, but he later found no relationship<br />

between these qualities in a large sample of FE<br />

students (Riding and Wigley 1997).<br />

The Cognitive Styles Analysis (CSA)<br />

Description of the measure<br />

Riding (1991a, 1991b, 1998a, 1998b) has developed<br />

a computerised assessment method called the<br />

Cognitive Styles Analysis (CSA). This is not a self-report<br />

measure, but presents cognitive tasks in such a way<br />

that it is not evident to the participant exactly what<br />

is being measured. The test items in the CSA for the<br />

holist-analytic dimension are all visual, and the scoring<br />

is based on a comparison of speed of response<br />

(not accuracy) on a matching task (holist preference)<br />

and on an embedded figures task (analytic preference).<br />

The items for the verbal-imagery dimension are all<br />

verbal and are based on relative speed of response<br />

to categorising items as being similar by virtue of their<br />

conceptual similarity (verbal preference) or colour<br />

(visual preference). The literacy demand of the verbal<br />

test is not high, as only single words are involved, but<br />

this has not been formally assessed. The instrument<br />

is suitable for use by adults and has been used in<br />

research studies with pupils as young as 9 years.<br />

Reliability and validity<br />

No information about the reliability of the CSA has<br />

been published by Riding. Using a sample of 50<br />

undergraduates, Peterson, Deary and Austin (2003a)<br />

report that the short-term test–retest reliability<br />

of the CSA verbal-imager dimension is very low<br />

and statistically not significant (r=0.27), while that<br />

of the holist-analytic dimension is also unsatisfactory<br />

in psychometric terms (r=0.53, p