learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

LSRC reference Section 6<br />

page 82/83<br />

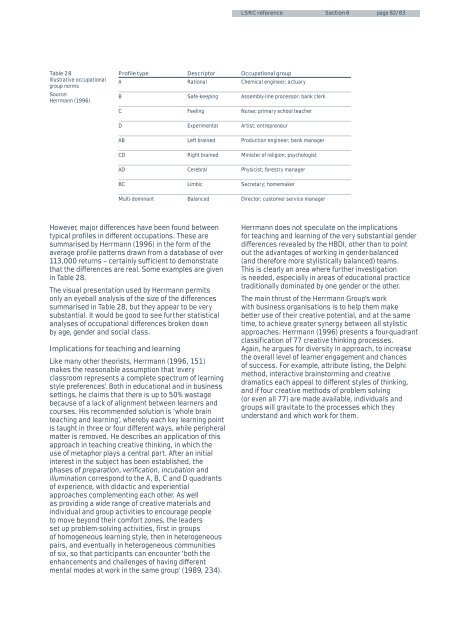

Table 28<br />

Illustrative occupational<br />

group norms<br />

Source:<br />

Herrmann (1996)<br />

Profile type<br />

A<br />

Descriptor<br />

Rational<br />

Occupational group<br />

Chemical engineer; actuary<br />

B<br />

Safe-keeping<br />

Assembly-line processor; bank clerk<br />

C<br />

Feeling<br />

Nurse; primary school teacher<br />

D<br />

Experimental<br />

Artist; entrepreneur<br />

AB<br />

Left brained<br />

Production engineer; bank manager<br />

CD<br />

Right brained<br />

Minister of religion; psychologist<br />

AD<br />

Cerebral<br />

Physicist; forestry manager<br />

BC<br />

Limbic<br />

Secretary; homemaker<br />

Multi-dominant<br />

Balanced<br />

Director; customer service manager<br />

However, major differences have been found between<br />

typical profiles in different occupations. These are<br />

summarised by Herrmann (1996) in the form of the<br />

average profile patterns drawn from a database of over<br />

113,000 returns – certainly sufficient to demonstrate<br />

that the differences are real. Some examples are given<br />

in Table 28.<br />

The visual presentation used by Herrmann permits<br />

only an eyeball analysis of the size of the differences<br />

summarised in Table 28, but they appear to be very<br />

substantial. It would be good to see further statistical<br />

analyses of occupational differences broken down<br />

by age, gender and social class.<br />

Implications for teaching and <strong>learning</strong><br />

Like many other theorists, Herrmann (1996, 151)<br />

makes the reasonable assumption that ‘every<br />

classroom represents a complete spectrum of <strong>learning</strong><br />

style preferences’. Both in educational and in business<br />

settings, he claims that there is up to 50% wastage<br />

because of a lack of alignment between learners and<br />

courses. His recommended solution is ‘whole brain<br />

teaching and <strong>learning</strong>’, whereby each key <strong>learning</strong> point<br />

is taught in three or four different ways, while peripheral<br />

matter is removed. He describes an application of this<br />

approach in teaching creative thinking, in which the<br />

use of metaphor plays a central part. After an initial<br />

interest in the subject has been established, the<br />

phases of preparation, verification, incubation and<br />

illumination correspond to the A, B, C and D quadrants<br />

of experience, with didactic and experiential<br />

approaches complementing each other. As well<br />

as providing a wide range of creative materials and<br />

individual and group activities to encourage people<br />

to move beyond their comfort zones, the leaders<br />

set up problem-solving activities, first in groups<br />

of homogeneous <strong>learning</strong> style, then in heterogeneous<br />

pairs, and eventually in heterogeneous communities<br />

of six, so that participants can encounter ‘both the<br />

enhancements and challenges of having different<br />

mental modes at work in the same group’ (1989, 234).<br />

Herrmann does not speculate on the implications<br />

for teaching and <strong>learning</strong> of the very substantial gender<br />

differences revealed by the HBDI, other than to point<br />

out the advantages of working in gender-balanced<br />

(and therefore more stylistically balanced) teams.<br />

This is clearly an area where further investigation<br />

is needed, especially in areas of educational practice<br />

traditionally dominated by one gender or the other.<br />

The main thrust of the Herrmann Group’s work<br />

with business organisations is to help them make<br />

better use of their creative potential, and at the same<br />

time, to achieve greater synergy between all stylistic<br />

approaches. Herrmann (1996) presents a four-quadrant<br />

classification of 77 creative thinking processes.<br />

Again, he argues for diversity in approach, to increase<br />

the overall level of learner engagement and chances<br />

of success. For example, attribute listing, the Delphi<br />

method, interactive brainstorming and creative<br />

dramatics each appeal to different <strong>styles</strong> of thinking,<br />

and if four creative methods of problem solving<br />

(or even all 77) are made available, individuals and<br />

groups will gravitate to the processes which they<br />

understand and which work for them.