learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

LSRC reference Section 7<br />

page 112/113<br />

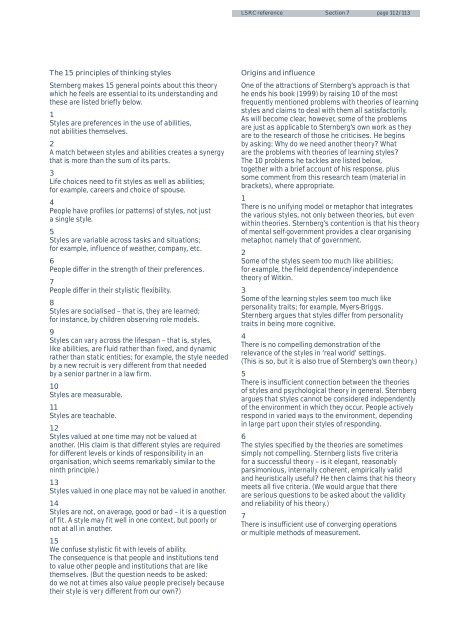

The 15 principles of thinking <strong>styles</strong><br />

Sternberg makes 15 general points about this theory<br />

which he feels are essential to its understanding and<br />

these are listed briefly below.<br />

1<br />

Styles are preferences in the use of abilities,<br />

not abilities themselves.<br />

2<br />

A match between <strong>styles</strong> and abilities creates a synergy<br />

that is more than the sum of its parts.<br />

3<br />

Life choices need to fit <strong>styles</strong> as well as abilities;<br />

for example, careers and choice of spouse.<br />

4<br />

People have profiles (or patterns) of <strong>styles</strong>, not just<br />

a single style.<br />

5<br />

Styles are variable across tasks and situations;<br />

for example, influence of weather, company, etc.<br />

6<br />

People differ in the strength of their preferences.<br />

7<br />

People differ in their stylistic flexibility.<br />

8<br />

Styles are socialised – that is, they are learned;<br />

for instance, by children observing role models.<br />

9<br />

Styles can vary across the lifespan – that is, <strong>styles</strong>,<br />

like abilities, are fluid rather than fixed, and dynamic<br />

rather than static entities; for example, the style needed<br />

by a new recruit is very different from that needed<br />

by a senior partner in a law firm.<br />

10<br />

Styles are measurable.<br />

11<br />

Styles are teachable.<br />

12<br />

Styles valued at one time may not be valued at<br />

another. (His claim is that different <strong>styles</strong> are required<br />

for different levels or kinds of responsibility in an<br />

organisation, which seems remarkably similar to the<br />

ninth principle.)<br />

13<br />

Styles valued in one place may not be valued in another.<br />

14<br />

Styles are not, on average, good or bad – it is a question<br />

of fit. A style may fit well in one context, but poorly or<br />

not at all in another.<br />

15<br />

We confuse stylistic fit with levels of ability.<br />

The consequence is that people and institutions tend<br />

to value other people and institutions that are like<br />

themselves. (But the question needs to be asked:<br />

do we not at times also value people precisely because<br />

their style is very different from our own?)<br />

Origins and influence<br />

One of the attractions of Sternberg’s approach is that<br />

he ends his book (1999) by raising 10 of the most<br />

frequently mentioned problems with theories of <strong>learning</strong><br />

<strong>styles</strong> and claims to deal with them all satisfactorily.<br />

As will become clear, however, some of the problems<br />

are just as applicable to Sternberg’s own work as they<br />

are to the research of those he criticises. He begins<br />

by asking: Why do we need another theory? What<br />

are the problems with theories of <strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong>?<br />

The 10 problems he tackles are listed below,<br />

together with a brief account of his response, plus<br />

some comment from this research team (material in<br />

brackets), where appropriate.<br />

1<br />

There is no unifying model or metaphor that integrates<br />

the various <strong>styles</strong>, not only between theories, but even<br />

within theories. Sternberg’s contention is that his theory<br />

of mental self-government provides a clear organising<br />

metaphor, namely that of government.<br />

2<br />

Some of the <strong>styles</strong> seem too much like abilities;<br />

for example, the field dependence/independence<br />

theory of Witkin.<br />

3<br />

Some of the <strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong> seem too much like<br />

personality traits; for example, Myers-Briggs.<br />

Sternberg argues that <strong>styles</strong> differ from personality<br />

traits in being more cognitive.<br />

4<br />

There is no compelling demonstration of the<br />

relevance of the <strong>styles</strong> in ‘real world’ settings.<br />

(This is so, but it is also true of Sternberg’s own theory.)<br />

5<br />

There is insufficient connection between the theories<br />

of <strong>styles</strong> and psychological theory in general. Sternberg<br />

argues that <strong>styles</strong> cannot be considered independently<br />

of the environment in which they occur. People actively<br />

respond in varied ways to the environment, depending<br />

in large part upon their <strong>styles</strong> of responding.<br />

6<br />

The <strong>styles</strong> specified by the theories are sometimes<br />

simply not compelling. Sternberg lists five criteria<br />

for a successful theory – is it elegant, reasonably<br />

parsimonious, internally coherent, empirically valid<br />

and heuristically useful? He then claims that his theory<br />

meets all five criteria. (We would argue that there<br />

are serious questions to be asked about the validity<br />

and reliability of his theory.)<br />

7<br />

There is insufficient use of converging operations<br />

or multiple methods of measurement.