learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

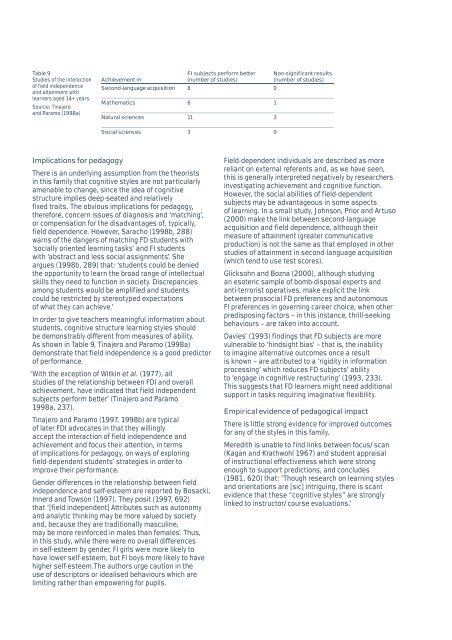

Table 9<br />

Studies of the interaction<br />

of field independence<br />

and attainment with<br />

learners aged 14+ years<br />

Source: Tinajero<br />

and Paramo (1998a)<br />

Achievement in:<br />

Second-language acquisition<br />

Mathematics<br />

Natural sciences<br />

FI subjects perform better<br />

(number of studies)<br />

8<br />

6<br />

11<br />

Non-significant results<br />

(number of studies)<br />

0<br />

1<br />

3<br />

Social sciences<br />

3<br />

0<br />

Implications for pedagogy<br />

There is an underlying assumption from the theorists<br />

in this family that cognitive <strong>styles</strong> are not particularly<br />

amenable to change, since the idea of cognitive<br />

structure implies deep-seated and relatively<br />

fixed traits. The obvious implications for pedagogy,<br />

therefore, concern issues of diagnosis and ‘matching’,<br />

or compensation for the disadvantages of, typically,<br />

field dependence. However, Saracho (1998b, 288)<br />

warns of the dangers of matching FD students with<br />

‘socially oriented <strong>learning</strong> tasks’ and FI students<br />

with ‘abstract and less social assignments’. She<br />

argues (1998b, 289) that: ‘students could be denied<br />

the opportunity to learn the broad range of intellectual<br />

skills they need to function in society. Discrepancies<br />

among students would be amplified and students<br />

could be restricted by stereotyped expectations<br />

of what they can achieve.’<br />

In order to give teachers meaningful information about<br />

students, cognitive structure <strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong> should<br />

be demonstrably different from measures of ability.<br />

As shown in Table 9, Tinajero and Paramo (1998a)<br />

demonstrate that field independence is a good predictor<br />

of performance.<br />

‘With the exception of Witkin et al. (1977), all<br />

studies of the relationship between FDI and overall<br />

achievement. have indicated that field independent<br />

subjects perform better’ (Tinajero and Paramo<br />

1998a, 237).<br />

Tinajero and Paramo (1997, 1998b) are typical<br />

of later FDI advocates in that they willingly<br />

accept the interaction of field independence and<br />

achievement and focus their attention, in terms<br />

of implications for pedagogy, on ways of exploring<br />

field-dependent students’ strategies in order to<br />

improve their performance.<br />

Gender differences in the relationship between field<br />

independence and self-esteem are reported by Bosacki,<br />

Innerd and Towson (1997). They posit (1997, 692)<br />

that ‘[field independent] Attributes such as autonomy<br />

and analytic thinking may be more valued by society<br />

and, because they are traditionally masculine,<br />

may be more reinforced in males than females’. Thus,<br />

in this study, while there were no overall differences<br />

in self-esteem by gender, FI girls were more likely to<br />

have lower self-esteem, but FI boys more likely to have<br />

higher self-esteem.The authors urge caution in the<br />

use of descriptors or idealised behaviours which are<br />

limiting rather than empowering for pupils.<br />

Field-dependent individuals are described as more<br />

reliant on external referents and, as we have seen,<br />

this is generally interpreted negatively by researchers<br />

investigating achievement and cognitive function.<br />

However, the social abilities of field-dependent<br />

subjects may be advantageous in some aspects<br />

of <strong>learning</strong>. In a small study, Johnson, Prior and Artuso<br />

(2000) make the link between second-language<br />

acquisition and field dependence, although their<br />

measure of attainment (greater communicative<br />

production) is not the same as that employed in other<br />

studies of attainment in second-language acquisition<br />

(which tend to use test scores).<br />

Glicksohn and Bozna (2000), although studying<br />

an esoteric sample of bomb-disposal experts and<br />

anti-terrorist operatives, make explicit the link<br />

between prosocial FD preferences and autonomous<br />

FI preferences in governing career choice, when other<br />

predisposing factors – in this instance, thrill-seeking<br />

behaviours – are taken into account.<br />

Davies’ (1993) findings that FD subjects are more<br />

vulnerable to ‘hindsight bias’ – that is, the inability<br />

to imagine alternative outcomes once a result<br />

is known – are attributed to a ‘rigidity in information<br />

processing’ which reduces FD subjects’ ability<br />

to ‘engage in cognitive restructuring’ (1993, 233).<br />

This suggests that FD learners might need additional<br />

support in tasks requiring imaginative flexibility.<br />

Empirical evidence of pedagogical impact<br />

There is little strong evidence for improved outcomes<br />

for any of the <strong>styles</strong> in this family.<br />

Meredith is unable to find links between focus/scan<br />

(Kagan and Krathwohl 1967) and student appraisal<br />

of instructional effectiveness which were strong<br />

enough to support predictions, and concludes<br />

(1981, 620) that: ‘Though research on <strong>learning</strong> <strong>styles</strong><br />

and orientations are [sic] intriguing, there is scant<br />

evidence that these “cognitive <strong>styles</strong>” are strongly<br />

linked to instructor/course evaluations.’