learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

LSRC reference Section 6<br />

page 86/87<br />

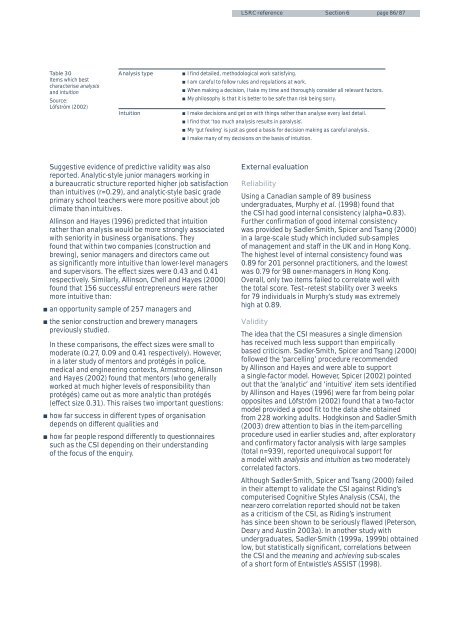

Table 30<br />

Items which best<br />

characterise analysis<br />

and intuition<br />

Source:<br />

Löfström (2002)<br />

Analysis type<br />

Intuition<br />

I find detailed, methodological work satisfying.<br />

I am careful to follow rules and regulations at work.<br />

When making a decision, I take my time and thoroughly consider all relevant factors.<br />

My philosophy is that it is better to be safe than risk being sorry.<br />

I make decisions and get on with things rather than analyse every last detail.<br />

I find that ‘too much analysis results in paralysis’.<br />

My ‘gut feeling’ is just as good a basis for decision making as careful analysis.<br />

I make many of my decisions on the basis of intuition.<br />

Suggestive evidence of predictive validity was also<br />

reported. Analytic-style junior managers working in<br />

a bureaucratic structure reported higher job satisfaction<br />

than intuitives (r=0.29), and analytic-style basic grade<br />

primary school teachers were more positive about job<br />

climate than intuitives.<br />

Allinson and Hayes (1996) predicted that intuition<br />

rather than analysis would be more strongly associated<br />

with seniority in business organisations. They<br />

found that within two companies (construction and<br />

brewing), senior managers and directors came out<br />

as significantly more intuitive than lower-level managers<br />

and supervisors. The effect sizes were 0.43 and 0.41<br />

respectively. Similarly, Allinson, Chell and Hayes (2000)<br />

found that 156 successful entrepreneurs were rather<br />

more intuitive than:<br />

an opportunity sample of 257 managers and<br />

the senior construction and brewery managers<br />

previously studied.<br />

In these comparisons, the effect sizes were small to<br />

moderate (0.27, 0.09 and 0.41 respectively). However,<br />

in a later study of mentors and protégés in police,<br />

medical and engineering contexts, Armstrong, Allinson<br />

and Hayes (2002) found that mentors (who generally<br />

worked at much higher levels of responsibility than<br />

protégés) came out as more analytic than protégés<br />

(effect size 0.31). This raises two important questions:<br />

how far success in different types of organisation<br />

depends on different qualities and<br />

how far people respond differently to questionnaires<br />

such as the CSI depending on their understanding<br />

of the focus of the enquiry.<br />

External evaluation<br />

Reliability<br />

Using a Canadian sample of 89 business<br />

undergraduates, Murphy et al. (1998) found that<br />

the CSI had good internal consistency (alpha=0.83).<br />

Further confirmation of good internal consistency<br />

was provided by Sadler-Smith, Spicer and Tsang (2000)<br />

in a large-scale study which included sub-samples<br />

of management and staff in the UK and in Hong Kong.<br />

The highest level of internal consistency found was<br />

0.89 for 201 personnel practitioners, and the lowest<br />

was 0.79 for 98 owner-managers in Hong Kong.<br />

Overall, only two items failed to correlate well with<br />

the total score. Test–retest stability over 3 weeks<br />

for 79 individuals in Murphy’s study was extremely<br />

high at 0.89.<br />

Validity<br />

The idea that the CSI measures a single dimension<br />

has received much less support than empirically<br />

based criticism. Sadler-Smith, Spicer and Tsang (2000)<br />

followed the ‘parcelling’ procedure recommended<br />

by Allinson and Hayes and were able to support<br />

a single-factor model. However, Spicer (2002) pointed<br />

out that the ‘analytic’ and ‘intuitive’ item sets identified<br />

by Allinson and Hayes (1996) were far from being polar<br />

opposites and Löfström (2002) found that a two-factor<br />

model provided a good fit to the data she obtained<br />

from 228 working adults. Hodgkinson and Sadler-Smith<br />

(2003) drew attention to bias in the item-parcelling<br />

procedure used in earlier studies and, after exploratory<br />

and confirmatory factor analysis with large samples<br />

(total n=939), reported unequivocal support for<br />

a model with analysis and intuition as two moderately<br />

correlated factors.<br />

Although Sadler-Smith, Spicer and Tsang (2000) failed<br />

in their attempt to validate the CSI against Riding’s<br />

computerised Cognitive Styles Analysis (CSA), the<br />

near-zero correlation reported should not be taken<br />

as a criticism of the CSI, as Riding’s instrument<br />

has since been shown to be seriously flawed (Peterson,<br />

Deary and Austin 2003a). In another study with<br />

undergraduates, Sadler-Smith (1999a, 1999b) obtained<br />

low, but statistically significant, correlations between<br />

the CSI and the meaning and achieving sub-scales<br />

of a short form of Entwistle’s ASSIST (1998).