learning-styles

learning-styles

learning-styles

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

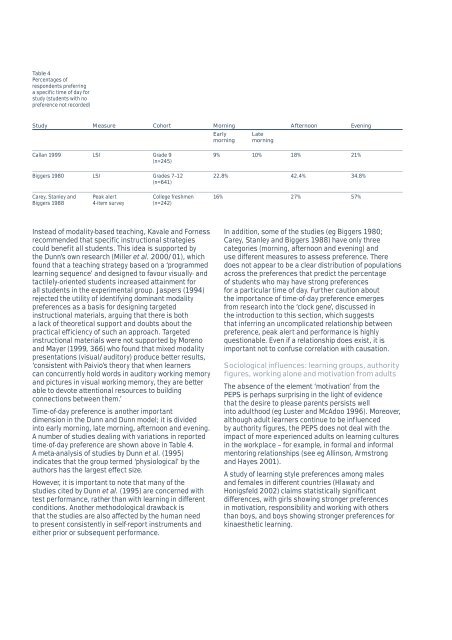

Table 4<br />

Percentages of<br />

respondents preferring<br />

a specific time of day for<br />

study (students with no<br />

preference not recorded)<br />

Study<br />

Measure<br />

Cohort<br />

Morning<br />

Early<br />

morning<br />

Late<br />

morning<br />

Afternoon<br />

Evening<br />

Callan 1999<br />

LSI<br />

Grade 9<br />

(n=245)<br />

9%<br />

10%<br />

18%<br />

21%<br />

Biggers 1980<br />

LSI<br />

Grades 7–12<br />

(n=641)<br />

22.8%<br />

42.4%<br />

34.8%<br />

Carey, Stanley and<br />

Biggers 1988<br />

Peak alert<br />

4-item survey<br />

College freshmen<br />

(n=242)<br />

16%<br />

27%<br />

57%<br />

Instead of modality-based teaching, Kavale and Forness<br />

recommended that specific instructional strategies<br />

could benefit all students. This idea is supported by<br />

the Dunn’s own research (Miller et al. 2000/01), which<br />

found that a teaching strategy based on a ‘programmed<br />

<strong>learning</strong> sequence’ and designed to favour visually- and<br />

tactilely-oriented students increased attainment for<br />

all students in the experimental group. Jaspers (1994)<br />

rejected the utility of identifying dominant modality<br />

preferences as a basis for designing targeted<br />

instructional materials, arguing that there is both<br />

a lack of theoretical support and doubts about the<br />

practical efficiency of such an approach. Targeted<br />

instructional materials were not supported by Moreno<br />

and Mayer (1999, 366) who found that mixed modality<br />

presentations (visual/auditory) produce better results,<br />

‘consistent with Paivio’s theory that when learners<br />

can concurrently hold words in auditory working memory<br />

and pictures in visual working memory, they are better<br />

able to devote attentional resources to building<br />

connections between them.’<br />

Time-of-day preference is another important<br />

dimension in the Dunn and Dunn model; it is divided<br />

into early morning, late morning, afternoon and evening.<br />

A number of studies dealing with variations in reported<br />

time-of-day preference are shown above in Table 4.<br />

A meta-analysis of studies by Dunn et al. (1995)<br />

indicates that the group termed ‘physiological’ by the<br />

authors has the largest effect size.<br />

However, it is important to note that many of the<br />

studies cited by Dunn et al. (1995) are concerned with<br />

test performance, rather than with <strong>learning</strong> in different<br />

conditions. Another methodological drawback is<br />

that the studies are also affected by the human need<br />

to present consistently in self-report instruments and<br />

either prior or subsequent performance.<br />

In addition, some of the studies (eg Biggers 1980;<br />

Carey, Stanley and Biggers 1988) have only three<br />

categories (morning, afternoon and evening) and<br />

use different measures to assess preference. There<br />

does not appear to be a clear distribution of populations<br />

across the preferences that predict the percentage<br />

of students who may have strong preferences<br />

for a particular time of day. Further caution about<br />

the importance of time-of-day preference emerges<br />

from research into the ‘clock gene’, discussed in<br />

the introduction to this section, which suggests<br />

that inferring an uncomplicated relationship between<br />

preference, peak alert and performance is highly<br />

questionable. Even if a relationship does exist, it is<br />

important not to confuse correlation with causation.<br />

Sociological influences: <strong>learning</strong> groups, authority<br />

figures, working alone and motivation from adults<br />

The absence of the element ‘motivation’ from the<br />

PEPS is perhaps surprising in the light of evidence<br />

that the desire to please parents persists well<br />

into adulthood (eg Luster and McAdoo 1996). Moreover,<br />

although adult learners continue to be influenced<br />

by authority figures, the PEPS does not deal with the<br />

impact of more experienced adults on <strong>learning</strong> cultures<br />

in the workplace – for example, in formal and informal<br />

mentoring relationships (see eg Allinson, Armstrong<br />

and Hayes 2001).<br />

A study of <strong>learning</strong> style preferences among males<br />

and females in different countries (Hlawaty and<br />

Honigsfeld 2002) claims statistically significant<br />

differences, with girls showing stronger preferences<br />

in motivation, responsibility and working with others<br />

than boys, and boys showing stronger preferences for<br />

kinaesthetic <strong>learning</strong>.