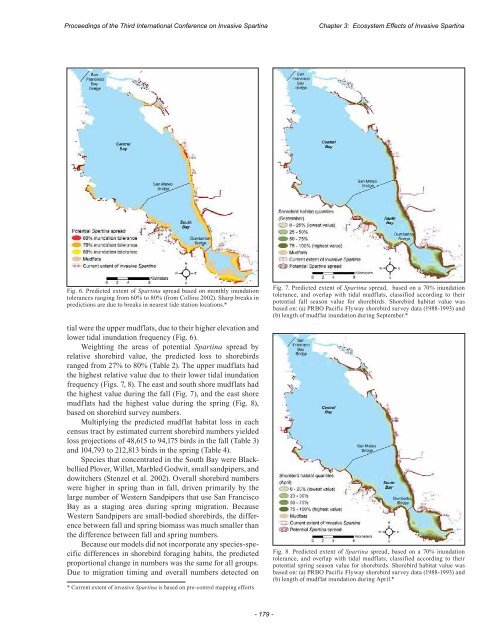

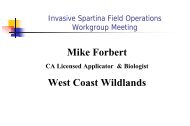

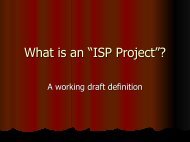

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaChapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaFig. 6. Predicted extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread based <strong>on</strong> m<strong>on</strong>thly inundati<strong>on</strong>tolerances ranging from 60% to 80% (from Collins 2002). Sharp breaks inpredicti<strong>on</strong>s are due to breaks in nearest tide stati<strong>on</strong> locati<strong>on</strong>s.*tial were <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> upper mudflats, due to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir higher elevati<strong>on</strong> andlower tidal inundati<strong>on</strong> frequency (Fig. 6).Weighting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential Spartina spread byrelative shorebird value, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> predicted loss to shorebirdsranged from 27% to 80% (Table 2). The upper mudflats had<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> highest relative value due to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir lower tidal inundati<strong>on</strong>frequency (Figs. 7, 8). The east and south shore mudflats had<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> highest value during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fall (Fig. 7), and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> east shoremudflats had <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> highest value during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> spring (Fig. 8),based <strong>on</strong> shorebird survey numbers.Multiplying <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> predicted mudflat habitat loss in eachcensus tract by estimated current shorebird numbers yieldedloss projecti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 48,615 to 94,175 birds in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fall (Table 3)and 104,793 to 212,813 birds in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> spring (Table 4).Species that c<strong>on</strong>centrated in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> South Bay were BlackbelliedPlover, Willet, Marbled Godwit, small sandpipers, anddowitchers (Stenzel et al. 2002). Overall shorebird numberswere higher in spring than in fall, driven primarily by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Western Sandpipers that use San FranciscoBay as a staging area during spring migrati<strong>on</strong>. BecauseWestern Sandpipers are small-bodied shorebirds, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> differencebetween fall and spring biomass was much smaller than<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> difference between fall and spring numbers.Because our models did not incorporate any species-specificdifferences in shorebird foraging habits, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> predictedproporti<strong>on</strong>al change in numbers was <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same for all groups.Due to migrati<strong>on</strong> timing and overall numbers detected <strong>on</strong>* Current extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasive Spartina is based <strong>on</strong> pre-c<strong>on</strong>trol mapping effortsFig. 7. Predicted extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread, based <strong>on</strong> a 70% inundati<strong>on</strong>tolerance, and overlap with tidal mudflats, classified according to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>irpotential fall seas<strong>on</strong> value for shorebirds. Shorebird habitat value wasbased <strong>on</strong>: (a) PRBO Pacific Flyway shorebird survey data (1988-1993) and(b) length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mudflat inundati<strong>on</strong> during September.*Fig. 8. Predicted extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread, based <strong>on</strong> a 70% inundati<strong>on</strong>tolerance, and overlap with tidal mudflats, classified according to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>irpotential spring seas<strong>on</strong> value for shorebirds. Shorebird habitat value wasbased <strong>on</strong>: (a) PRBO Pacific Flyway shorebird survey data (1988-1993) and(b) length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mudflat inundati<strong>on</strong> during April.*- 179 -

Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaTable 3. Predicted loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fall shorebird numbers by species, based <strong>on</strong> arange <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread scenarios. All predicti<strong>on</strong>s assume that mudflatsare at carrying capacity, and that mudflat habitat value is proporti<strong>on</strong>al totidal inundati<strong>on</strong>.Table 4. Predicted loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spring shorebird numbers by species, based <strong>on</strong> arange <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread scenarios. All predicti<strong>on</strong>s assume that mudflatsare at carrying capacity, and that mudflat habitat value is proporti<strong>on</strong>al totidal inundati<strong>on</strong>.CurrentScenario 1:60%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceScenario 2:70%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceScenario 3:80%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceCurrentScenario 1:60%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceScenario 2:70%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceScenario 3:80%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceMudflatHectares6,062 -904 -1,988 -3,269MudflatHectares6,062 -904 -1,988 -3,269Bird Numbers:AmericanAvocetBlack-belliedPlover5,023 -1,701 -3,034 -4,1018,138 -2,756 -4,916 -6,645Dowitcher 13,377 -4,530 -8,081 -10,923L<strong>on</strong>g-billedCurlewMarbledGodwit371 -126 -224 -30314,251 -4,826 -8,609 -11,636Red Knot 1,678 -568 -1,014 -1,370SemipalmatedPlover1,501 -508 -907 -1,225Willet 15,612 -5,286 -9,431 -12,747Westernand LeastSandpiper,160,374 -54,305 -96,880 -130,948DunlinTotal 220,325 -48,615 -70,055 -94,175Bird Numbers:AmericanAvocetBlack-belliedPlover844 -263 -476 -6564,595 -1,432 -2,590 -3,570Dowitchers 33,008 -10,289 -18,608 -25,644L<strong>on</strong>g-billedCurlewMarbledGodwit218 -68 -123 -16913,437 -4,188 -7,575 -10,439Red Knot 503 -157 -284 -391SemipalmatedPlover725 -226 -409 -563Willet 2,112 -658 -1,191 -1,641Westernand LeastSandpiper,Dunlin450,817 -140,528 -254,137 -350,241Total 506,259 -104,793 -156,097 -212,813shorebird surveys, Spartina spread would have <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> biggestnumerical impact <strong>on</strong> small shorebirds, dowitchers, andMarbled Godwits (Tables 3, 4). Willets and Black-belliedPlovers would be most affected during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fall, when <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>irnumbers are highest. In terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> total bird biomass (seeStenzel et al. 2002), <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> largest predicted losses were in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>spring, due to higher overall biomass densities (Table 5).DISCUSSIONThe results presented herein are based <strong>on</strong> several basicassumpti<strong>on</strong>s, all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which should be examined in fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rdetail in order to restrict <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wide range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predicted shorebirdlosses. Our most fundamental assumpti<strong>on</strong> was that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>mudflat habitats were at carrying capacity during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> falland spring survey periods. However, it is possible that <strong>on</strong>lypreferred areas are functi<strong>on</strong>ing at carrying capacity (Goss-Custard 1979). If individuals could switch to lower-qualitymudflat areas without significantly affecting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir overallfitness, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds may have been overestimated(Goss-Custard 2003). Anecdotal evidence suggeststhat San Francisco Bay mudflats may reach carrying capacityduring <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> winter, when storm-related flooding may promptsome species to move inland to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Central Valley (Warnocket al. 1995; Takekawa et al. 2002) but we do not know if mudflatsand neighboring tidal and salt p<strong>on</strong>d habitats are at carryingcapacity during migrati<strong>on</strong>. Currently, we lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> data <strong>on</strong>mudflat food resources, shorebird energetics, and individualforaging behavior (especially prey preference) that would benecessary to obtain an estimate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carrying capacity.A potential bias in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r directi<strong>on</strong>, however, was thatour models examined <strong>on</strong>ly <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower limits <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spreadand <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> subsequent impacts <strong>on</strong> shorebird habitat value. Inreality, upward Spartina spread may pose an equally seriousthreat to shorebirds as mudflats al<strong>on</strong>g tidal channels andopen areas within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsh plain are col<strong>on</strong>ized by invasiveSpartina and become unavailable to foraging shorebirds.Table 5. Predicted loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fall and spring shorebird biomass, based <strong>on</strong> a range<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread scenarios (1-3). All predicti<strong>on</strong>s assume that muflats areat carrying capacity, and that mudflat habitat value is proporti<strong>on</strong>al to tidalinundati<strong>on</strong>.Fallbiomass(kg)Springbiomass(kg)CurrentScenario 1:60%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceScenario 2:70%inundati<strong>on</strong>toleranceScenario 3:80%inundati<strong>on</strong>tolerance21,416 -6,245 -12,263 -17,06725,289 -6,884 -13,560 -19,202- 180 -

- Page 2 and 3:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 4 and 5:

FORWARD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe <stro

- Page 6 and 7:

TABLE OF CONTENTSForward & Acknowle

- Page 9 and 10:

Community Spartina Education and St

- Page 11 and 12:

included the docum

- Page 14:

CHAPTER ONESpartina Biology

- Page 17 and 18:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 19 and 20:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 21 and 22:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 23 and 24:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 25 and 26:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 28 and 29:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 30 and 31:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 32 and 33:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 34:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 37 and 38:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 39 and 40:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 42 and 43:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 44:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 47 and 48:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 49 and 50:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 51 and 52:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 53 and 54:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 55 and 56:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 57 and 58:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 60 and 61:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 62 and 63:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 64 and 65:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 66:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 69 and 70:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 71 and 72:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 74 and 75:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 76:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 79 and 80:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 81 and 82:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 83 and 84:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 86 and 87:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 88 and 89:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 90 and 91:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 92 and 93:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 94 and 95:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 96 and 97:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 98:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 101 and 102:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 103 and 104:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 105 and 106:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 108 and 109:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 110:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 113 and 114:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 115 and 116:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 117 and 118:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 119 and 120:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 122 and 123:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 124 and 125:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 126 and 127:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 128:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 131 and 132:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 134 and 135:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 136 and 137:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 138 and 139:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 140:

CHAPTER THREEEcosystem Effects <str

- Page 143 and 144: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 145 and 146: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 148 and 149: Proceedings <stron

- Page 150 and 151: Proceedings <stron

- Page 152: Proceedings <stron

- Page 155 and 156: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 157 and 158: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 160 and 161: Proceedings <stron

- Page 162 and 163: Proceedings <stron

- Page 164: Proceedings <stron

- Page 167 and 168: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 169 and 170: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 171 and 172: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 174 and 175: Proceedings <stron

- Page 176: Proceedings <stron

- Page 179 and 180: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 181 and 182: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 184 and 185: Proceedings <stron

- Page 186 and 187: Proceedings <stron

- Page 188 and 189: Proceedings <stron

- Page 190 and 191: Proceedings <stron

- Page 194 and 195: Proceedings <stron

- Page 196: Proceedings <stron

- Page 199 and 200: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 201 and 202: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 204 and 205: Proceedings <stron

- Page 206 and 207: Proceedings <stron

- Page 208 and 209: Proceedings <stron

- Page 210 and 211: Proceedings <stron

- Page 212: Proceedings <stron

- Page 216 and 217: Proceedings <stron

- Page 218 and 219: Proceedings <stron

- Page 220 and 221: Proceedings <stron

- Page 222 and 223: Proceedings <stron

- Page 224 and 225: Proceedings <stron

- Page 226 and 227: Proceedings <stron

- Page 228 and 229: Proceedings <stron

- Page 230 and 231: Proceedings <stron

- Page 232 and 233: Proceedings <stron

- Page 234 and 235: Proceedings <stron

- Page 236 and 237: Proceedings <stron

- Page 238 and 239: Proceedings <stron

- Page 240 and 241: Proceedings <stron

- Page 242 and 243:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 244 and 245:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 246:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 249 and 250:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 251 and 252:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 253 and 254:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 255 and 256:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 257 and 258:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 259 and 260:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 261 and 262:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 263 and 264:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 265 and 266:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 267 and 268:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 269 and 270:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 271 and 272:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 273 and 274:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 276 and 277:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 278 and 279:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 280 and 281:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 282 and 283:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 284 and 285:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 286 and 287:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 288 and 289:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 290:

Proceedings <stron