<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaChapter 2: Spartina Distributi<strong>on</strong> and SpreadREMOTE SENSING,LIDAR AND GIS INFORM LANDSCAPE AND POPULATION ECOLOGY,WILLAPA BAY,WASHINGTONJ.C. CIVILLE 1,4 ,S.D.SMITH 2 AND D.R. STRONG 31 Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Evoluti<strong>on</strong> and Ecology, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, Davis, One Shields Ave., Davis, CA 95616-87552 True North GIS, 4857 Grand Fir Lane, Olympia, WA 985023 Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Evoluti<strong>on</strong> and Ecology, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, Davis, One Shields Ave., Davis, CA 95616-87554 Current address: 2731 Be<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>l St. NE, Olympia, WA 98506; jciville@comcast.netKeywords: Spartina alterniflora, Willapa Bay, photogrammetry, mappingThe spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina alterniflora Loisel. (smoothcordgrass, hereafter referred to as Spartina) in PacificNorthwest estuaries presents a unique opportunity toexamine ecological interacti<strong>on</strong>s between an invasive cl<strong>on</strong>alorganism and local abiotic factors. Willapa Bay is a large,shallow, tidal basin <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> southwest coast <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Washingt<strong>on</strong>State. The bay is approximately 360 square kilometers (km 2 )at mean high tide, with well over 190 km 2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>t mud andsand tideflats exposed at mean low tide (Civille 2005). Themixed diurnal tides <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Pacific coast distinguishWashingt<strong>on</strong> estuaries from those <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Atlantic coast whereS. alterniflora is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> predominant native salt marsh species.Spartina species are <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> principle comp<strong>on</strong>ents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Atlanticand Gulf coast estuaries, but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> introducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina to<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Willapa Bay estuary and its open mudflats has led to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rapid c<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thousands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> intertidal hectares intodense stands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> upper tidal meadows (Sayce 1988; Daehlerand Str<strong>on</strong>g 1996; Civille et al. 2005). The rapid expansi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>this robust cl<strong>on</strong>al grass across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> open habitat <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> intertidalmudflats is a textbook example <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> unimpeded col<strong>on</strong>izati<strong>on</strong>,and presents challenges not <strong>on</strong>ly to management efforts, butto ecologists as well.The initial questi<strong>on</strong>s relevant to this research weregenerated by biologists and land managers in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Washingt<strong>on</strong>, who needed to understand Spartina expansi<strong>on</strong>for envir<strong>on</strong>mental impact analyses, adaptive managementplans, and to direct c<strong>on</strong>trol efforts in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> most efficientmanner (Sayce 1988; Aberle 1990; Aberle 1993; Civille1993). These questi<strong>on</strong>s included: where were plantsspreading fastest, where was intertidal habitat being lostmost rapidly, and whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r stopping seed producti<strong>on</strong> wasmore effective than removing as many new plants aspossible (Moody and Mack 1988). Ecologists studyinginvasive populati<strong>on</strong> growth dynamics ask similar questi<strong>on</strong>s.What is regulating <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina <strong>on</strong> Willapa Baymudflats? Are <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se regulators density dependent orindependent? With <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> seemingly limitless expanse <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat available for col<strong>on</strong>izati<strong>on</strong>, why is it that some areasare filling in more quickly than o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rs? Are <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re factorsintrinsic to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> biology and mating system <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina thatinfluence its spread, or are abiotic factors more important inshaping <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> col<strong>on</strong>izati<strong>on</strong> fr<strong>on</strong>ts? Does competiti<strong>on</strong> betweenSpartina plants limit <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>, and will availability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>resources affect <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir growth? Have evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary changestaken place in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Willapa Bay populati<strong>on</strong> that allowSpartina to compete more effectively? Many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sequesti<strong>on</strong>s have been addressed in experimental and<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>oretical work by members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina BiocomplexityGroup at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California at Davis, (Davis et al.2004a; Davis et al. 2004b; Taylor 2004; Taylor and Hastings2004; Civille 2005; Davis 2005; Civille 2006) and werepresented at this c<strong>on</strong>ference by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir primary authors (Daviset al.; Taylor et al.; this volume).Spartina was probably brought to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Willapa estuarythrough <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> transplanting <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern oysters to bolster <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>flagging oyster industry <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Willapa Bay in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1890s andearly 1900s. The California gold rush had fueled <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>depleti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> native oysters from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bay, and an effort wasmade by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> United States Fisheries Bureau to replant <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>bay with Chesapeake stock. The completi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>transc<strong>on</strong>tinental railway allowed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> trip to be made in abouta week (Townsend 1896; Scheffer 1945; Civille et al. 2005),and eastern oysters c<strong>on</strong>tinued to be brought via railcar toWillapa until around 1917. The climate was apparently toocool for eastern oysters, and although <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y grew well, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ywere never able to reproduce successfully in Willapa atcommercially viable levels. Spartina, however, was able toestablish in small col<strong>on</strong>ies that were close to beds used torear eastern oysters (Civille et al. 2005).The first written and photographic evidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartinapresence in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary was ga<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>red at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Willapa Nati<strong>on</strong>alWildlife Refuge by T.H. Scheffer in 1940 (Scheffer 1945).A photograph taken by Scheffer shows several “greenislands,” and was d<strong>on</strong>ated to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California Academy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Science Herbarium to document his findings. If an averageheight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>e meter (m) is assumed, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> large plant in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>photo is about 42 m in diameter, covering approximately1,367 square meters (m 2 ) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mudflat. The first aerialphotographs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bay were taken by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Army Corps <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Engineers in 1945, and Spartina plants <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a similar size to-83-

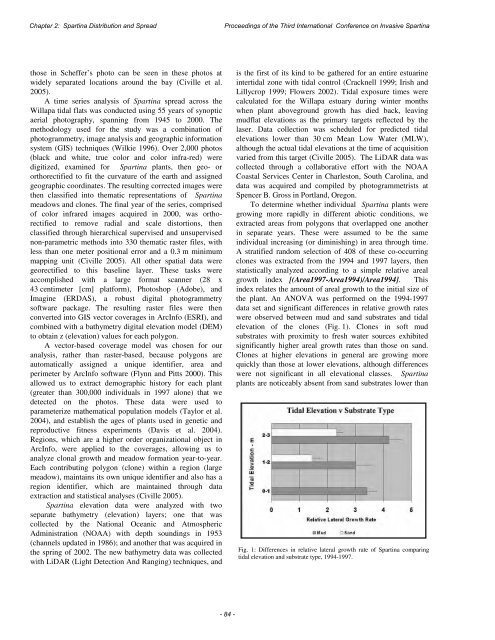

Chapter 2: Spartina Distributi<strong>on</strong> and Spread<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartinathose in Scheffer’s photo can be seen in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se photos atwidely separated locati<strong>on</strong>s around <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bay (Civille et al.2005).A time series analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina spread across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>Willapa tidal flats was c<strong>on</strong>ducted using 55 years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> synopticaerial photography, spanning from 1945 to 2000. Themethodology used for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study was a combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>photogrammetry, image analysis and geographic informati<strong>on</strong>system (GIS) techniques (Wilkie 1996). Over 2,000 photos(black and white, true color and color infra-red) weredigitized, examined for Spartina plants, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n geo- ororthorectified to fit <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> curvature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> earth and assignedgeographic coordinates. The resulting corrected images were<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n classified into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>matic representati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartinameadows and cl<strong>on</strong>es. The final year <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> series, comprised<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> color infrared images acquired in 2000, was orthorectifiedto remove radial and scale distorti<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>nclassified through hierarchical supervised and unsupervisedn<strong>on</strong>-parametric methods into 330 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>matic raster files, withless than <strong>on</strong>e meter positi<strong>on</strong>al error and a 0.3 m minimummapping unit (Civille 2005). All o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r spatial data weregeorectified to this baseline layer. These tasks wereaccomplished with a large format scanner (28 x43 centimeter [cm] platform), Photoshop (Adobe), andImagine (ERDAS), a robust digital photogrammetrys<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tware package. The resulting raster files were <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>nc<strong>on</strong>verted into GIS vector coverages in ArcInfo (ESRI), andcombined with a bathymetry digital elevati<strong>on</strong> model (DEM)to obtain z (elevati<strong>on</strong>) values for each polyg<strong>on</strong>.A vector-based coverage model was chosen for ouranalysis, ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than raster-based, because polyg<strong>on</strong>s areautomatically assigned a unique identifier, area andperimeter by ArcInfo s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>tware (Flynn and Pitts 2000). Thisallowed us to extract demographic history for each plant(greater than 300,000 individuals in 1997 al<strong>on</strong>e) that wedetected <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> photos. These data were used toparameterize ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>matical populati<strong>on</strong> models (Taylor et al.2004), and establish <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plants used in genetic andreproductive fitness experiments (Davis et al. 2004).Regi<strong>on</strong>s, which are a higher order organizati<strong>on</strong>al object inArcInfo, were applied to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> coverages, allowing us toanalyze cl<strong>on</strong>al growth and meadow formati<strong>on</strong> year-to-year.Each c<strong>on</strong>tributing polyg<strong>on</strong> (cl<strong>on</strong>e) within a regi<strong>on</strong> (largemeadow), maintains its own unique identifier and also has aregi<strong>on</strong> identifier, which are maintained through dataextracti<strong>on</strong> and statistical analyses (Civille 2005).Spartina elevati<strong>on</strong> data were analyzed with twoseparate bathymetry (elevati<strong>on</strong>) layers; <strong>on</strong>e that wascollected by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nati<strong>on</strong>al Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministrati<strong>on</strong> (NOAA) with depth soundings in 1953(channels updated in 1986); and ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r that was acquired in<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> spring <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2002. The new bathymetry data was collectedwith LiDAR (Light Detecti<strong>on</strong> And Ranging) techniques, andis <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its kind to be ga<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>red for an entire estuarineintertidal z<strong>on</strong>e with tidal c<strong>on</strong>trol (Cracknell 1999; Irish andLillycrop 1999; Flowers 2002). Tidal exposure times werecalculated for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Willapa estuary during winter m<strong>on</strong>thswhen plant aboveground growth has died back, leavingmudflat elevati<strong>on</strong>s as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary targets reflected by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>laser. Data collecti<strong>on</strong> was scheduled for predicted tidalelevati<strong>on</strong>s lower than 30 cm Mean Low Water (MLW),although <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> actual tidal elevati<strong>on</strong>s at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acquisiti<strong>on</strong>varied from this target (Civille 2005). The LiDAR data wascollected through a collaborative effort with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> NOAACoastal Services Center in Charlest<strong>on</strong>, South Carolina, anddata was acquired and compiled by photogrammetrists atSpencer B. Gross in Portland, Oreg<strong>on</strong>.To determine whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r individual Spartina plants weregrowing more rapidly in different abiotic c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, weextracted areas from polyg<strong>on</strong>s that overlapped <strong>on</strong>e ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rin separate years. These were assumed to be <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sameindividual increasing (or diminishing) in area through time.A stratified random selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 408 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se co-occurringcl<strong>on</strong>es was extracted from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1994 and 1997 layers, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>nstatistically analyzed according to a simple relative arealgrowth index [(Area1997-Area1994)/Area1994]. Thisindex relates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> areal growth to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> initial size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant. An ANOVA was performed <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1994-1997data set and significant differences in relative growth rateswere observed between mud and sand substrates and tidalelevati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cl<strong>on</strong>es (Fig. 1). Cl<strong>on</strong>es in s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>t mudsubstrates with proximity to fresh water sources exhibitedsignificantly higher areal growth rates than those <strong>on</strong> sand.Cl<strong>on</strong>es at higher elevati<strong>on</strong>s in general are growing morequickly than those at lower elevati<strong>on</strong>s, although differenceswere not significant in all elevati<strong>on</strong>al classes. Spartinaplants are noticeably absent from sand substrates lower thanFig. 1: Differences in relative lateral growth rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina comparingtidal elevati<strong>on</strong> and substrate type, 1994-1997.-84-