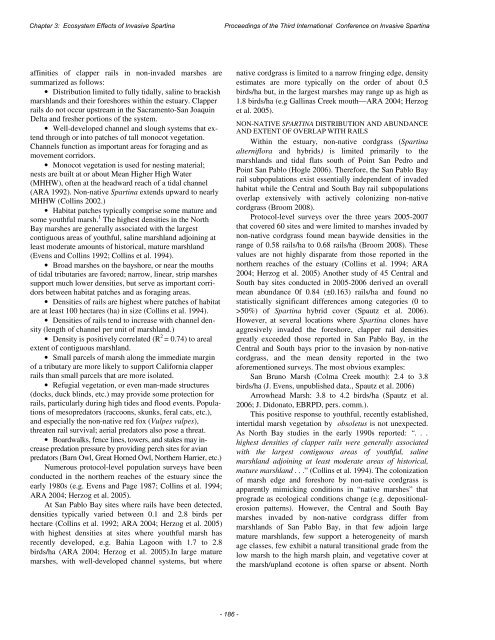

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaChapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaNON-NATIVE CORDGRASS AND THE CALIFORNIA CLAPPER RAIL:BIOGEOGRAPHICALOVERLAP BETWEEN AN INVASIVE PLANT AND AN ENDANGERED BIRDJ. EVENS 1 ,K.ZAREMBA 2 , AND J. ALBERTSON 31Avocet Research Associates, P.O. Box 839, Point Reyes Stati<strong>on</strong>, CA 94956; email: jevens@svn.net2San Francisco Estuary <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina Project, 2612-A 8 th St., Berkeley, CA 947102Current address: 971 Village Dr. Bowen Island, BC, V0N 1G0 Canada; katyzaremba@yahoo.ca3 D<strong>on</strong> Edwards San Francisco Bay Nati<strong>on</strong>al Wildlife Refuge, 9500 Thornt<strong>on</strong> Ave.,Newark, CA 94560-3300The federally endangered California clapper rail (Rallus l<strong>on</strong>girostris obsoletus) is a tidal marshdependentbird whose distributi<strong>on</strong> is restricted entirely to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco Estuary. The nativecordgrass, Spartina foliosa, has l<strong>on</strong>g been recognized as a critical comp<strong>on</strong>ent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rail habitatwithin <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary. The distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rail has been m<strong>on</strong>itoredintermittently since <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mid-1970s and that effort has increased since <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> early 1990s. Thec<strong>on</strong>current invasi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bay’s tidal marshes by n<strong>on</strong>-native Spartina alterniflora and its hybridswith S. foliosa has impacted clapper rail abundance and distributi<strong>on</strong> in some areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary. Inthis paper we discuss: (1) habitat affinities and density estimates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rail in invaded and n<strong>on</strong>-invadedmarshes; (2) <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-native Spartina relative to that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rails over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last15 years; and, (3) potential impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> changing marsh ecology <strong>on</strong> rail distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance inboth <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> near term and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<strong>on</strong>g term.Keywords: California clapper rail, Rallus l<strong>on</strong>girostris obsoletus, Spartina, cordgrass, impacts,habitat characteristics, distributi<strong>on</strong>, abundanceCLAPPER RAIL DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT AFFINITIES ANDABUNDANCEFormerly more widespread al<strong>on</strong>g California’s outercoast (e.g. Morro Bay, Elkhorn Slough, Tomales Bay), <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>breeding distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> California clapper rail is nowrestricted entirely to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Francisco Estuary (Alberts<strong>on</strong>and Evens 2000). Within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rail ispatchily distributed through tidally influenced marshes, withpopulati<strong>on</strong> centers fairly evenly dispersed am<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> SouthBay and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> North Bay (aka “San Pablo Bay”) marshes. TheCentral Bay also hosts significant populati<strong>on</strong>s, but, like <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se tend to be relatively discrete and locallyclustered (e.g. Arrowhead Marsh, San Bruno Marsh, CorteMadera marshes). In Suisun Bay, distributi<strong>on</strong> is very spotty,densities are apparently low, and occurrence may besporadic, especially in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn reaches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Suisun Marsh(Collins et al. 1994; Alberts<strong>on</strong> and Evens 2000; Estrella2007). Indeed, no clapper rails were detected in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Suisunsystem in 2005 or 2007 (Herzog et al. 2005; Estrella 2007).The most recent populati<strong>on</strong> estimates suggest thatapproximately 1500 California clapper rails remain in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>San Francisco Estuary with approximately <strong>on</strong>e-third <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong> in San Pablo Bay and two-thirds in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Centraland South bays, combined (Alberts<strong>on</strong> and Evens 2000;Avocet Research Associates 2004; USFWS unpubl. data).This compares with estimates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 4200-6000 rails in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mid-1970s (Gill 1979). However <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se numbers require a caveat:Populati<strong>on</strong> estimates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rails are fraught withuncertainty, survey coverage is sporadic, and numbers mayvary widely from year-to-year.CALIFORNIA CLAPPER RAIL HABITATCHARACTERISTICS: PRE-INVASIONHabitat availability and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> characteristics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tidalmarshes differ between South, Central, and North Baymarshlands. In general, marshlands in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn reachesare more extensive and less modified by human activity thanthose in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> central and sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn porti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary.Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, invasi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary by n<strong>on</strong>-nativeSpartina—c<strong>on</strong>fined largely to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>estuary (http://www.spartina.org/maps.htm)—has amplifiedthis disparity.Synoptic surveys <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> North Bay marshes (north <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> PointsSan Pedro and San Pablo) in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> early 1990s describedhabitat use in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn reaches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary (Evens andCollins 1992; Collins et al. 1994). We assume that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>seecological parameters most closely resemble habitatpreferences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California clapper rail’s prior to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extensivemodificati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary that began in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mid-1800s(C<strong>on</strong>omos 1979; Goals Project 1999). Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, earlierstudies throughout <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary described distributi<strong>on</strong>,abundance, and habitat affinities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> obsoletus prior toinvasi<strong>on</strong> by n<strong>on</strong>-native Spartina (Grinnell and Miller 1944;Gill 1979; Avocet Research 1992; Evens and Collins 1992;Collins et al. 1994; Alberts<strong>on</strong> 1995). Generalized habitat- 185 -

Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartina<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> Spartinaaffinities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rails in n<strong>on</strong>-invaded marshes aresummarized as follows:• Distributi<strong>on</strong> limited to fully tidally, saline to brackishmarshlands and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir foreshores within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary. Clapperrails do not occur upstream in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sacramento-San JoaquinDelta and fresher porti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> system.• Well-developed channel and slough systems that extendthrough or into patches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tall m<strong>on</strong>ocot vegetati<strong>on</strong>.Channels functi<strong>on</strong> as important areas for foraging and asmovement corridors.• M<strong>on</strong>ocot vegetati<strong>on</strong> is used for nesting material;nests are built at or about Mean Higher High Water(MHHW), <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> headward reach <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a tidal channel(ARA 1992). N<strong>on</strong>-native Spartina extends upward to nearlyMHHW (Collins 2002.)• Habitat patches typically comprise some mature andsome youthful marsh. 1 The highest densities in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> NorthBay marshes are generally associated with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> largestc<strong>on</strong>tiguous areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> youthful, saline marshland adjoining atleast moderate amounts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> historical, mature marshland(Evens and Collins 1992; Collins et al. 1994).• Broad marshes <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bayshore, or near <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mouths<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tidal tributaries are favored; narrow, linear, strip marshessupport much lower densities, but serve as important corridorsbetween habitat patches and as foraging areas.• Densities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rails are highest where patches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitatare at least 100 hectares (ha) in size (Collins et al. 1994).• Densities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rails tend to increase with channel density(length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> channel per unit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marshland.)• Density is positively correlated (R 2 = 0.74) to arealextent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tiguous marshland.• Small parcels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsh al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> immediate margin<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a tributary are more likely to support California clapperrails than small parcels that are more isolated.• Refugial vegetati<strong>on</strong>, or even man-made structures(docks, duck blinds, etc.) may provide some protecti<strong>on</strong> forrails, particularly during high tides and flood events. Populati<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mesopredators (racco<strong>on</strong>s, skunks, feral cats, etc.),and especially <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-native red fox (Vulpes vulpes),threaten rail survival; aerial predators also pose a threat.• Boardwalks, fence lines, towers, and stakes may increasepredati<strong>on</strong> pressure by providing perch sites for avianpredators (Barn Owl, Great Horned Owl, Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Harrier, etc.)Numerous protocol-level populati<strong>on</strong> surveys have beenc<strong>on</strong>ducted in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn reaches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary since <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>early 1980s (e.g. Evens and Page 1987; Collins et al. 1994;ARA 2004; Herzog et al. 2005).At San Pablo Bay sites where rails have been detected,densities typically varied between 0.1 and 2.8 birds perhectare (Collins et al. 1992; ARA 2004; Herzog et al. 2005)with highest densities at sites where youthful marsh hasrecently developed, e.g. Bahia Lago<strong>on</strong> with 1.7 to 2.8birds/ha (ARA 2004; Herzog et al. 2005).In large maturemarshes, with well-developed channel systems, but wherenative cordgrass is limited to a narrow fringing edge, densityestimates are more typically <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> order <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> about 0.5birds/ha but, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> largest marshes may range up as high as1.8 birds/ha (e.g Gallinas Creek mouth—ARA 2004; Herzoget al. 2005).NON-NATIVE SPARTINA DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCEAND EXTENT OF OVERLAP WITH RAILSWithin <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary, n<strong>on</strong>-native cordgrass (Spartinaalterniflora and hybrids) is limited primarily to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>marshlands and tidal flats south <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Point San Pedro andPoint San Pablo (Hogle 2006). Therefore, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Pablo Bayrail subpopulati<strong>on</strong>s exist essentially independent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invadedhabitat while <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Central and South Bay rail subpopulati<strong>on</strong>soverlap extensively with actively col<strong>on</strong>izing n<strong>on</strong>-nativecordgrass (Broom 2008).Protocol-level surveys over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> three years 2005-2007that covered 60 sites and were limited to marshes invaded byn<strong>on</strong>-native cordgrass found mean baywide densities in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 0.58 rails/ha to 0.68 rails/ha (Broom 2008). Thesevalues are not highly disparate from those reported in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn reaches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estuary (Collins et al. 1994; ARA2004; Herzog et al. 2005) Ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r study <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 45 Central andSouth bay sites c<strong>on</strong>ducted in 2005-2006 derived an overallmean abundance 0f 0.84 (±0.163) rails/ha and found nostatistically significant differences am<strong>on</strong>g categories (0 to>50%) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina hybrid cover (Spautz et al. 2006).However, at several locati<strong>on</strong>s where Spartina cl<strong>on</strong>es haveaggresively invaded <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> foreshore, clapper rail densitiesgreatly exceeded those reported in San Pablo Bay, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>Central and South bays prior to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasi<strong>on</strong> by n<strong>on</strong>-nativecordgrass, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean density reported in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> twoaforementi<strong>on</strong>ed surveys. The most obvious examples:San Bruno Marsh (Colma Creek mouth): 2.4 to 3.8birds/ha (J. Evens, unpublished data., Spautz et al. 2006)Arrowhead Marsh: 3.8 to 4.2 birds/ha (Spautz et al.2006; J. Did<strong>on</strong>ato, EBRPD, pers. comm.).This positive resp<strong>on</strong>se to youthful, recently established,intertidal marsh vegetati<strong>on</strong> by obsoletus is not unexpected.As North Bay studies in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> early 1990s reported: “. . .highest densities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> clapper rails were generally associatedwith <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> largest c<strong>on</strong>tiguous areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> youthful, salinemarshland adjoining at least moderate areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> historical,mature marshland . . .” (Collins et al. 1994). The col<strong>on</strong>izati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsh edge and foreshore by n<strong>on</strong>-native cordgrass isapparently mimicking c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s in “native marshes” thatprograde as ecological c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s change (e.g. depositi<strong>on</strong>alerosi<strong>on</strong>patterns). However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Central and South Baymarshes invaded by n<strong>on</strong>-native cordgrass differ frommarshlands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Pablo Bay, in that few adjoin largemature marshlands, few support a heterogeneity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marshage classes, few exhibit a natural transiti<strong>on</strong>al grade from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>low marsh to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> high marsh plain, and vegetative cover at<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsh/upland ecot<strong>on</strong>e is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten sparse or absent. North- 186 -

- Page 2 and 3:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 4 and 5:

FORWARD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe <stro

- Page 6 and 7:

TABLE OF CONTENTSForward & Acknowle

- Page 9 and 10:

Community Spartina Education and St

- Page 11 and 12:

included the docum

- Page 14:

CHAPTER ONESpartina Biology

- Page 17 and 18:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 19 and 20:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 21 and 22:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 23 and 24:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 25 and 26:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 28 and 29:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 30 and 31:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 32 and 33:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 34:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 37 and 38:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 39 and 40:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 42 and 43:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 44:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 47 and 48:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 49 and 50:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 51 and 52:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 53 and 54:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 55 and 56:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 57 and 58:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 60 and 61:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 62 and 63:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 64 and 65:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 66:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 69 and 70:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 71 and 72:

Chapter 1: Spartina Biology

- Page 74 and 75:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 76:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 79 and 80:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 81 and 82:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 83 and 84:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 86 and 87:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 88 and 89:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 90 and 91:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 92 and 93:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 94 and 95:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 96 and 97:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 98:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 101 and 102:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 103 and 104:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 105 and 106:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 108 and 109:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 110:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 113 and 114:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 115 and 116:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 117 and 118:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 119 and 120:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 122 and 123:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 124 and 125:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 126 and 127:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 128:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 131 and 132:

Chapter 2: Spartina Distribution an

- Page 134 and 135:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 136 and 137:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 138 and 139:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 140:

CHAPTER THREEEcosystem Effects <str

- Page 143 and 144:

Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 145 and 146:

Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 148 and 149: Proceedings <stron

- Page 150 and 151: Proceedings <stron

- Page 152: Proceedings <stron

- Page 155 and 156: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 157 and 158: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 160 and 161: Proceedings <stron

- Page 162 and 163: Proceedings <stron

- Page 164: Proceedings <stron

- Page 167 and 168: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 169 and 170: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 171 and 172: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 174 and 175: Proceedings <stron

- Page 176: Proceedings <stron

- Page 179 and 180: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 181 and 182: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 184 and 185: Proceedings <stron

- Page 186 and 187: Proceedings <stron

- Page 188 and 189: Proceedings <stron

- Page 190 and 191: Proceedings <stron

- Page 192 and 193: Proceedings <stron

- Page 194 and 195: Proceedings <stron

- Page 196: Proceedings <stron

- Page 201 and 202: Chapter 3: Ecosystem Effects <stron

- Page 204 and 205: Proceedings <stron

- Page 206 and 207: Proceedings <stron

- Page 208 and 209: Proceedings <stron

- Page 210 and 211: Proceedings <stron

- Page 212: Proceedings <stron

- Page 216 and 217: Proceedings <stron

- Page 218 and 219: Proceedings <stron

- Page 220 and 221: Proceedings <stron

- Page 222 and 223: Proceedings <stron

- Page 224 and 225: Proceedings <stron

- Page 226 and 227: Proceedings <stron

- Page 228 and 229: Proceedings <stron

- Page 230 and 231: Proceedings <stron

- Page 232 and 233: Proceedings <stron

- Page 234 and 235: Proceedings <stron

- Page 236 and 237: Proceedings <stron

- Page 238 and 239: Proceedings <stron

- Page 240 and 241: Proceedings <stron

- Page 242 and 243: Proceedings <stron

- Page 244 and 245: Proceedings <stron

- Page 246: Proceedings <stron

- Page 249 and 250:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 251 and 252:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 253 and 254:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 255 and 256:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 257 and 258:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 259 and 260:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 261 and 262:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 263 and 264:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 265 and 266:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 267 and 268:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 269 and 270:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 271 and 272:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 273 and 274:

Chapter 4: Spartina Control and Man

- Page 276 and 277:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 278 and 279:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 280 and 281:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 282 and 283:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 284 and 285:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 286 and 287:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 288 and 289:

Proceedings <stron

- Page 290:

Proceedings <stron