Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Invasive ...

Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Invasive ...

Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Invasive ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

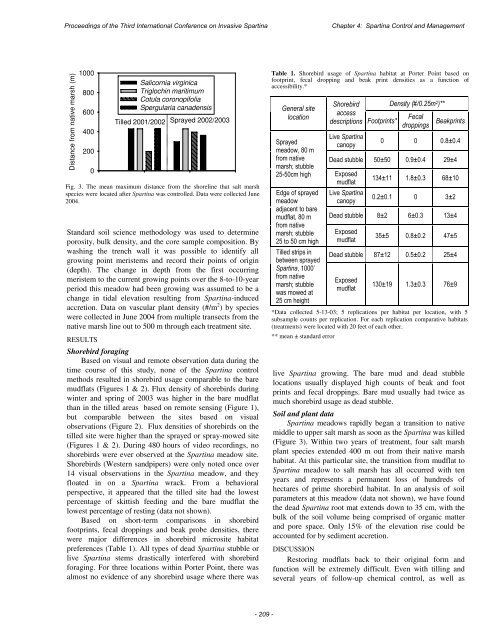

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Proceedings</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Third</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Internati<strong>on</strong>al</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>ference</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Invasive</strong> SpartinaChapter 4: Spartina C<strong>on</strong>trol and ManagementDistance from native marsh (m)10008006004002000Salicornia virginicaTriglochin maritimumCotula cor<strong>on</strong>opifoliaSpergularia canadensisTilled 2001/2002Sprayed 2002/2003Fig. 3. The mean maximum distance from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> shoreline that salt marshspecies were located after Spartina was c<strong>on</strong>trolled. Data were collected June2004.Standard soil science methodology was used to determineporosity, bulk density, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> core sample compositi<strong>on</strong>. Bywashing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> trench wall it was possible to identify allgrowing point meristems and record <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir points <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> origin(depth). The change in depth from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first occurringmeristem to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> current growing points over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 8-to-10-yearperiod this meadow had been growing was assumed to be achange in tidal elevati<strong>on</strong> resulting from Spartina-inducedaccreti<strong>on</strong>. Data <strong>on</strong> vascular plant density (#/m 2 ) by specieswere collected in June 2004 from multiple transects from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>native marsh line out to 500 m through each treatment site.RESULTSShorebird foragingBased <strong>on</strong> visual and remote observati<strong>on</strong> data during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>time course <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study, n<strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina c<strong>on</strong>trolmethods resulted in shorebird usage comparable to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> baremudflats (Figures 1 & 2). Flux density <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shorebirds duringwinter and spring <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2003 was higher in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bare mudflatthan in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tilled areas based <strong>on</strong> remote sensing (Figure 1),but comparable between <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sites based <strong>on</strong> visualobservati<strong>on</strong>s (Figure 2). Flux densities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shorebirds <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>tilled site were higher than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sprayed or spray-mowed site(Figures 1 & 2). During 480 hours <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> video recordings, noshorebirds were ever observed at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina meadow site.Shorebirds (Western sandpipers) were <strong>on</strong>ly noted <strong>on</strong>ce over14 visual observati<strong>on</strong>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina meadow, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>yfloated in <strong>on</strong> a Spartina wrack. From a behavioralperspective, it appeared that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tilled site had <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lowestpercentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> skittish feeding and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bare mudflat <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>lowest percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> resting (data not shown).Based <strong>on</strong> short-term comparis<strong>on</strong>s in shorebirdfootprints, fecal droppings and beak probe densities, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rewere major differences in shorebird microsite habitatpreferences (Table 1). All types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dead Spartina stubble orlive Spartina stems drastically interfered with shorebirdforaging. For three locati<strong>on</strong>s within Porter Point, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re wasalmost no evidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any shorebird usage where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re wasTable 1. Shorebird usage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina habitat at Porter Point based <strong>on</strong>footprint, fecal dropping and beak print densities as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>accessibility.*General sitelocati<strong>on</strong>Sprayedmeadow, 80 mfrom nativemarsh; stubble25-50cm highEdge <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sprayedmeadowadjacent to baremudflat, 80 mfrom nativemarsh; stubble25 to 50 cm highTilled strips inbetween sprayedSpartina, 1000’from nativemarsh; stubblewas mowed at25 cm heightShorebirdaccessdescripti<strong>on</strong>s Footprints*Live SpartinacanopyDensity (#/0.25m 2 )**FecaldroppingsBeakprints0 0 0.8±0.4Dead stubble 50±50 0.9±0.4 29±4ExposedmudflatLive Spartinacanopy134±11 1.8±0.3 68±100.2±0.1 0 3±2Dead stubble 8±2 6±0.3 13±4Exposedmudflat35±5 0.8±0.2 47±5Dead stubble 87±12 0.5±0.2 25±4Exposedmudflat130±19 1.3±0.3 76±9*Data collected 5-13-03; 5 replicati<strong>on</strong>s per habitat per locati<strong>on</strong>, with 5subsample counts per replicati<strong>on</strong>. For each replicati<strong>on</strong> comparative habitats(treatments) were located with 20 feet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r.** mean ± standard errorlive Spartina growing. The bare mud and dead stubblelocati<strong>on</strong>s usually displayed high counts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> beak and footprints and fecal droppings. Bare mud usually had twice asmuch shorebird usage as dead stubble.Soil and plant dataSpartina meadows rapidly began a transiti<strong>on</strong> to nativemiddle to upper salt marsh as so<strong>on</strong> as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spartina was killed(Figure 3). Within two years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> treatment, four salt marshplant species extended 400 m out from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir native marshhabitat. At this particular site, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> transiti<strong>on</strong> from mudflat toSpartina meadow to salt marsh has all occurred with tenyears and represents a permanent loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hundreds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>hectares <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> prime shorebird habitat. In an analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> soilparameters at this meadow (data not shown), we have found<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> dead Spartina root mat extends down to 35 cm, with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>bulk <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> soil volume being comprised <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> organic matterand pore space. Only 15% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> elevati<strong>on</strong> rise could beaccounted for by sediment accreti<strong>on</strong>.DISCUSSIONRestoring mudflats back to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir original form andfuncti<strong>on</strong> will be extremely difficult. Even with tilling andseveral years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> follow-up chemical c<strong>on</strong>trol, as well as- 209 -