Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia - Jurusan Antropologi ...

Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia - Jurusan Antropologi ...

Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia - Jurusan Antropologi ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

216 STRATIFICATION AND MOBILITY IN URBAN CHINA<br />

Party. In terms of occupational class, some important tendencies too are evident.<br />

Only <strong>in</strong> the cadre class are a large fraction of members <strong>in</strong> the ‘new rich’ category<br />

(19.5 per cent). In contrast, 7.6 per cent of professionals count as new rich–most<br />

professionals (47.5 per cent) are medium <strong>in</strong>come, as they tend to work <strong>in</strong> state<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutions such as schools <strong>and</strong> research <strong>in</strong>stitutes which pay only relatively low<br />

wages. But taken together, cadres <strong>and</strong> professionals make up just under half of the<br />

new rich (45.1 per cent), with a further 22 per cent work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> upper non-manual<br />

occupations. A smaller, but significant number of the new rich are <strong>in</strong> lower-status<br />

jobs, especially as <strong>in</strong>dividual bus<strong>in</strong>ess operators (getihu), 14.3 per cent of whom are<br />

<strong>in</strong> the high-<strong>in</strong>come category. Thus, even these simple comparisons make an<br />

important po<strong>in</strong>t that has perhaps been neglected <strong>in</strong> recent work which has<br />

concentrated on private bus<strong>in</strong>ess as the source of new wealth <strong>in</strong> urban Ch<strong>in</strong>a: most<br />

high-<strong>in</strong>come earners <strong>in</strong> larger Ch<strong>in</strong>ese cities are not household bus<strong>in</strong>ess operators<br />

but members of an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly visible middle class of cadres <strong>and</strong> professionals<br />

whose organisational <strong>and</strong> human capital resources, rather than pure<br />

entrepreneurial ability, give them an advantaged position <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s<br />

commercialis<strong>in</strong>g economy.<br />

Factors shap<strong>in</strong>g the values, lifestyle <strong>and</strong> cultural profile of a status group are to<br />

be found not only <strong>in</strong> the characteristics of the group itself, but also <strong>in</strong> the<br />

background of the people who become members of that group. Thus, the next<br />

basic is: what are the social backgrounds of those people who make it <strong>in</strong>to urban<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s highest <strong>in</strong>come brackets?<br />

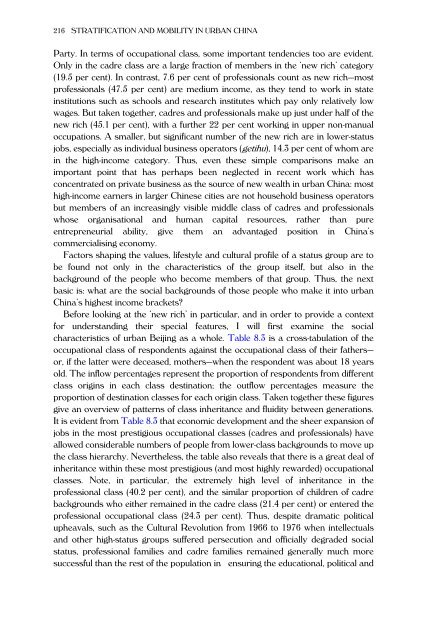

Before look<strong>in</strong>g at the ‘new rich’ <strong>in</strong> particular, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> order to provide a context<br />

for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g their special features, I will first exam<strong>in</strong>e the social<br />

characteristics of urban Beij<strong>in</strong>g as a whole. Table 8.3 is a cross-tabulation of the<br />

occupational class of respondents aga<strong>in</strong>st the occupational class of their fathers–<br />

or, if the latter were deceased, mothers–when the respondent was about 18 years<br />

old. The <strong>in</strong>flow percentages represent the proportion of respondents from different<br />

class orig<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> each class dest<strong>in</strong>ation; the outflow percentages measure the<br />

proportion of dest<strong>in</strong>ation classes for each orig<strong>in</strong> class. Taken together these figures<br />

give an overview of patterns of class <strong>in</strong>heritance <strong>and</strong> fluidity between generations.<br />

It is evident from Table 8.3 that economic development <strong>and</strong> the sheer expansion of<br />

jobs <strong>in</strong> the most prestigious occupational classes (cadres <strong>and</strong> professionals) have<br />

allowed considerable numbers of people from lower-class backgrounds to move up<br />

the class hierarchy. Nevertheless, the table also reveals that there is a great deal of<br />

<strong>in</strong>heritance with<strong>in</strong> these most prestigious (<strong>and</strong> most highly rewarded) occupational<br />

classes. Note, <strong>in</strong> particular, the extremely high level of <strong>in</strong>heritance <strong>in</strong> the<br />

professional class (40.2 per cent), <strong>and</strong> the similar proportion of children of cadre<br />

backgrounds who either rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the cadre class (21.4 per cent) or entered the<br />

professional occupational class (24.3 per cent). Thus, despite dramatic political<br />

upheavals, such as the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 when <strong>in</strong>tellectuals<br />

<strong>and</strong> other high-status groups suffered persecution <strong>and</strong> officially degraded social<br />

status, professional families <strong>and</strong> cadre families rema<strong>in</strong>ed generally much more<br />

successful than the rest of the population <strong>in</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g the educational, political <strong>and</strong>