ESTONIAN ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW 2009

ESTONIAN ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW 2009

ESTONIAN ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW 2009

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

3.4. Hunting<br />

Hunting is closely related to the rural economy and<br />

the field of nature conservation. Wild game is one component<br />

of the usable natural resources, and the reasons<br />

for the use of various species are diverse. Currently the<br />

main focus of hunting lies on bi-ungulates (cloven hoofed<br />

mammals), which are hunted for meat and for sport.<br />

Hunting for middle-size and small predators (racoon<br />

dog, fox, pine marten, mink) has acquired more of a<br />

conservation character due to the depressed market for<br />

furs; abundance of these species is regulated in connection<br />

with their possible negative impact on other species.<br />

In the case of beaver, the need to hunt this species is<br />

related to the damage they cause, primarily in drained<br />

forest areas. Large predators (wolf, bear, lynx) are hunted<br />

mainly for sport; there are also efforts to regulate their<br />

populations as they feed on bi-ungulates, which are in<br />

the main sphere of interest of hunting. Aside from this,<br />

wolves can cause significant losses for sheep farmers, and<br />

bears pose a risk to apiculture.<br />

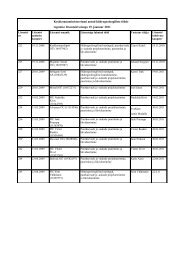

The abundance of moose has fluctuated greatly in<br />

the last 17 years and in recent years has stabilized at a<br />

more or less acceptable level for different interest groups<br />

(figure 3.18), where as a renewable hunting resource<br />

the animal has a good potential for population growth.<br />

At the same time, the forest damage caused by moose<br />

remains within tolerable limits. At the beginning of<br />

the 1990s, moose numbers had grown too high and the<br />

damage caused to forests, consisting primarily of damage<br />

to middle-aged stands of spruce, was beyond tolerable<br />

limits. The obligatory hunting quotas set over the course<br />

of a number of years were significantly higher than the<br />

natural net population change and led to a rapid decline<br />

in moose numbers. Thanks to corrections to the hunting<br />

quotas, the declining trend was reversed in the mid-<br />

1990s and the population continued to rise until 2005,<br />

at which point the situation stabilized. As the abundance<br />

of moose increased, the damage caused to forests grew,<br />

especially to young stands of pine. To ease the situation,<br />

in 2006–2007 moose were hunted slightly in excess of<br />

natural population increase.<br />

20 000<br />

15 000<br />

population size<br />

hunting bag<br />

10 000<br />

number of individuals<br />

5 000<br />

0<br />

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008<br />

Figure 3.18. Moose census and hunting from 1990–2008. Data: Centre for Forest Protection and Siviculture.<br />

51