POLLINATORS POLLINATION AND FOOD PRODUCTION

individual_chapters_pollination_20170305

individual_chapters_pollination_20170305

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THE ASSESSMENT REPORT ON <strong>POLLINATORS</strong>, <strong>POLLINATION</strong> <strong>AND</strong> <strong>FOOD</strong> <strong>PRODUCTION</strong><br />

crop price from any individual asset are likely to be small<br />

resulting in little to no welfare loss. At a basic level, yield<br />

analysis can be used in conjunction with regression analysis<br />

to estimate the benefits of pollinator capital from habitats<br />

at different distances to the crop (e.g., Olschewski et al.,<br />

2006). However, detailed production function models<br />

(Section 2.2.3) are ideal as they can produce estimates<br />

that more accurately represent the quality of services<br />

produced from particular habitat patches (e.g., Ricketts and<br />

Lonsdorf, 2013). Furthermore, they can also examine the<br />

substitution patterns between pollination and other capital<br />

inputs. However, the highly specific nature of these models<br />

makes it unlikely that they can be widely employed at<br />

present, necessitating a focus on using biophysical units of<br />

pollinator capital.<br />

Unlike other measures of pollination value, quantifications<br />

of pollinator stocks should account for potential as well<br />

as realized pollination services as assets may not always<br />

be able to provide services. For example, if arable farmers<br />

within the landscape around a source of pollinator capital<br />

(Figure 4.3) regularly rotate their production between<br />

pollinated and non-pollinated crops, the assets will still<br />

have value as stocks of pollination even in years where no<br />

pollinated crops are grown as they still have the potential to<br />

contribute to crop production.<br />

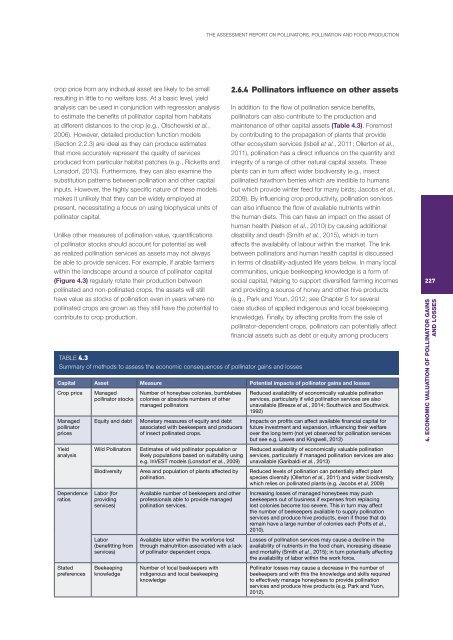

TABLE 4.3<br />

Summary of methods to assess the economic consequences of pollinator gains and losses<br />

2.6.4 Pollinators influence on other assets<br />

In addition to the flow of pollination service benefits,<br />

pollinators can also contribute to the production and<br />

maintenance of other capital assets (Table 4.3). Foremost<br />

by contributing to the propagation of plants that provide<br />

other ecosystem services (Isbell et al., 2011; Ollerton et al.,<br />

2011), pollination has a direct influence on the quantity and<br />

integrity of a range of other natural capital assets. These<br />

plants can in turn affect wider biodiversity (e.g., insect<br />

pollinated hawthorn berries which are inedible to humans<br />

but which provide winter feed for many birds; Jacobs et al.,<br />

2009). By influencing crop productivity, pollination services<br />

can also influence the flow of available nutrients within<br />

the human diets. This can have an impact on the asset of<br />

human health (Nelson et al., 2010) by causing additional<br />

disability and death (Smith et al., 2015), which in turn<br />

affects the availability of labour within the market. The link<br />

between pollinators and human health capital is discussed<br />

in terms of disability-adjusted life years below. In many local<br />

communities, unique beekeeping knowledge is a form of<br />

social capital, helping to support diversified farming incomes<br />

and providing a source of honey and other hive products<br />

(e.g., Park and Youn, 2012; see Chapter 5 for several<br />

case studies of applied indigenous and local beekeeping<br />

knowledge). Finally, by affecting profits from the sale of<br />

pollinator-dependent crops, pollinators can potentially affect<br />

financial assets such as debt or equity among producers<br />

Capital Asset Measure Potential impacts of pollinator gains and losses<br />

Crop price<br />

Managed<br />

pollinator<br />

prices<br />

Yield<br />

analysis<br />

Dependence<br />

ratios<br />

Stated<br />

preferences<br />

Managed<br />

pollinator stocks<br />

Equity and debt<br />

Wild Pollinators<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Labor (for<br />

providing<br />

services)<br />

Labor<br />

(benefitting from<br />

services)<br />

Beekeeping<br />

knowledge<br />

Number of honeybee colonies, bumblebee<br />

colonies or absolute numbers of other<br />

managed pollinators<br />

Monetary measures of equity and debt<br />

associated with beekeepers and producers<br />

of insect pollinated crops.<br />

Estimates of wild pollinator population or<br />

likely populations based on suitability using<br />

e.g. InVEST models (Lonsdorf et al., 2009)<br />

Area and population of plants affected by<br />

pollination.<br />

Available number of beekeepers and other<br />

professionals able to provide managed<br />

pollination services.<br />

Available labor within the workforce lost<br />

through malnutrition associated with a lack<br />

of pollinator dependent crops.<br />

Number of local beekeepers with<br />

indigenous and local beekeeping<br />

knowledge<br />

Reduced availability of economically valuable pollination<br />

services, particularly if wild pollination services are also<br />

unavailable (Breeze et al., 2014; Southwick and Southwick.<br />

1992)<br />

Impacts on profits can affect available financial capital for<br />

future investment and expansion, influencing their welfare<br />

over the long term (not yet observed for pollination services<br />

but see e.g. Lawes and Kingwell, 2012)<br />

Reduced availability of economically valuable pollination<br />

services, particularly if managed pollination services are also<br />

unavailable (Garibaldi et al., 2013)<br />

Reduced levels of pollination can potentially affect plant<br />

species diversity (Ollerton et al., 2011) and wider biodiversity<br />

which relies on pollinated plants (e.g. Jacobs et al, 2009)<br />

Increasing losses of managed honeybees may push<br />

beekeepers out of business if expenses from replacing<br />

lost colonies become too severe. This in turn may affect<br />

the number of beekeepers available to supply pollination<br />

services and produce hive products, even if those that do<br />

remain have a large number of colonies each (Potts et al.,<br />

2010).<br />

Losses of pollination services may cause a decline in the<br />

availability of nutrients in the food chain, increasing disease<br />

and mortality (Smith et al., 2015); in turn potentially affecting<br />

the availability of labor within the work force.<br />

Pollinator losses may cause a decrease in the number of<br />

beekeepers and with this the knowledge and skills required<br />

to effectively manage honeybees to provide pollination<br />

services and produce hive products (e.g. Park and Yuon,<br />

2012).<br />

227<br />

4. ECONOMIC VALUATION OF POLLINATOR GAINS<br />

<strong>AND</strong> LOSSES