POLLINATORS POLLINATION AND FOOD PRODUCTION

individual_chapters_pollination_20170305

individual_chapters_pollination_20170305

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THE ASSESSMENT REPORT ON <strong>POLLINATORS</strong>, <strong>POLLINATION</strong> <strong>AND</strong> <strong>FOOD</strong> <strong>PRODUCTION</strong><br />

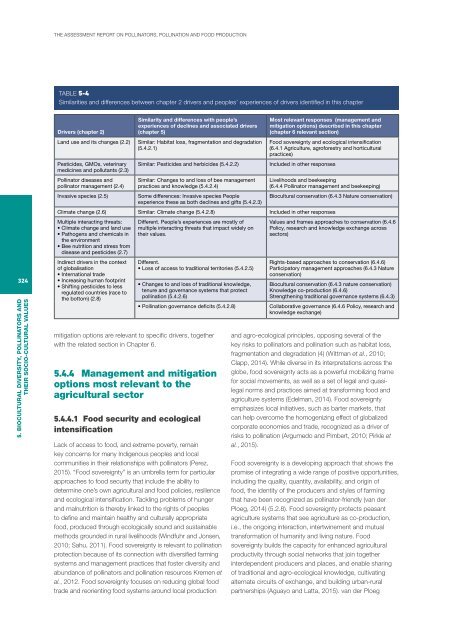

TABLE 5-4<br />

Similarities and differences between chapter 2 drivers and peoples’ experiences of drivers identified in this chapter<br />

324<br />

5. BIOCULTURAL DIVERSITY, <strong>POLLINATORS</strong> <strong>AND</strong><br />

THEIR SOCIO-CULTURAL VALUES<br />

Drivers (chapter 2)<br />

Land use and its changes (2.2)<br />

Pesticides, GMOs, veterinary<br />

medicines and pollutants (2.3)<br />

Pollinator diseases and<br />

pollinator management (2.4)<br />

Invasive species (2.5)<br />

Similarity and differences with people’s<br />

experiences of declines and associated drivers<br />

(chapter 5)<br />

Similar: Habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation<br />

(5.4.2.1)<br />

Similar: Pesticides and herbicides (5.4.2.2)<br />

Similar: Changes to and loss of bee management<br />

practices and knowledge (5.4.2.4)<br />

Some differences: Invasive species People<br />

experience these as both declines and gifts (5.4.2.3)<br />

mitigation options are relevant to specific drivers, together<br />

with the related section in Chapter 6.<br />

5.4.4 Management and mitigation<br />

options most relevant to the<br />

agricultural sector<br />

5.4.4.1 Food security and ecological<br />

intensification<br />

Lack of access to food, and extreme poverty, remain<br />

key concerns for many Indigenous peoples and local<br />

communities in their relationships with pollinators (Perez,<br />

2015). “Food sovereignty” is an umbrella term for particular<br />

approaches to food security that include the ability to<br />

determine one’s own agricultural and food policies, resilience<br />

and ecological intensification. Tackling problems of hunger<br />

and malnutrition is thereby linked to the rights of peoples<br />

to define and maintain healthy and culturally appropriate<br />

food, produced through ecologically sound and sustainable<br />

methods grounded in rural livelihoods (Windfuhr and Jonsen,<br />

2010; Sahu, 2011). Food sovereignty is relevant to pollination<br />

protection because of its connection with diversified farming<br />

systems and management practices that foster diversity and<br />

abundance of pollinators and pollination resources Kremen et<br />

al., 2012. Food sovereignty focuses on reducing global food<br />

trade and reorienting food systems around local production<br />

Most relevant responses (management and<br />

mitigation options) described in this chapter<br />

(chapter 6 relevant section)<br />

Food sovereignty and ecological intensification<br />

(6.4.1 Agriculture, agroforestry and horticultural<br />

practices)<br />

Included in other responses<br />

Livelihoods and beekeeping<br />

(6.4.4 Pollinator management and beekeeping)<br />

Biocultural conservation (6.4.3 Nature conservation)<br />

Climate change (2.6) Similar: Climate change (5.4.2.8) Included in other responses<br />

Multiple interacting threats:<br />

• Climate change and land use<br />

• Pathogens and chemicals in<br />

the environment<br />

• Bee nutrition and stress from<br />

disease and pesticides (2.7)<br />

Indirect drivers in the context<br />

of globalisation<br />

• International trade<br />

• Increasing human footprint<br />

• Shifting pesticides to less<br />

regulated countries (race to<br />

the bottom) (2.8)<br />

Different. People’s experiences are mostly of<br />

multiple interacting threats that impact widely on<br />

their values.<br />

Different.<br />

• Loss of access to traditional territories (5.4.2.5)<br />

• Changes to and loss of traditional knowledge,<br />

tenure and governance systems that protect<br />

pollination (5.4.2.6)<br />

• Pollination governance deficits (5.4.2.8)<br />

Values and frames approaches to conservation (6.4.6<br />

Policy, research and knowledge exchange across<br />

sectors)<br />

Rights-based approaches to conservation (6.4.6)<br />

Participatory management approaches (6.4.3 Nature<br />

conservation)<br />

Biocultural conservation (6.4.3 nature conservation)<br />

Knowledge co-production (6.4.6)<br />

Strengthening traditional governance systems (6.4.3)<br />

Collaborative governance (6.4.6 Policy, research and<br />

knowledge exchange)<br />

and agro-ecological principles, opposing several of the<br />

key risks to pollinators and pollination such as habitat loss,<br />

fragmentation and degradation (4) (Wittman et al., 2010;<br />

Clapp, 2014). While diverse in its interpretations across the<br />

globe, food sovereignty acts as a powerful mobilizing frame<br />

for social movements, as well as a set of legal and quasilegal<br />

norms and practices aimed at transforming food and<br />

agriculture systems (Edelman, 2014). Food sovereignty<br />

emphasizes local initiatives, such as barter markets, that<br />

can help overcome the homogenizing effect of globalized<br />

corporate economies and trade, recognized as a driver of<br />

risks to pollination (Argumedo and Pimbert, 2010; Pirkle et<br />

al., 2015).<br />

Food sovereignty is a developing approach that shows the<br />

promise of integrating a wide range of positive opportunities,<br />

including the quality, quantity, availability, and origin of<br />

food, the identity of the producers and styles of farming<br />

that have been recognized as pollinator-friendly (van der<br />

Ploeg, 2014) (5.2.8). Food sovereignty protects peasant<br />

agriculture systems that see agriculture as co-production,<br />

i.e., the ongoing interaction, intertwinement and mutual<br />

transformation of humanity and living nature. Food<br />

sovereignty builds the capacity for enhanced agricultural<br />

productivity through social networks that join together<br />

interdependent producers and places, and enable sharing<br />

of traditional and agro-ecological knowledge, cultivating<br />

alternate circuits of exchange, and building urban-rural<br />

partnerships (Aguayo and Latta, 2015). van der Ploeg