intervention strategies for renovation of social housing estates

intervention strategies for renovation of social housing estates

intervention strategies for renovation of social housing estates

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A Dutch case study. The Bijlmermeer, Amsterdam Zuidoost. Chapter 5<br />

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------<br />

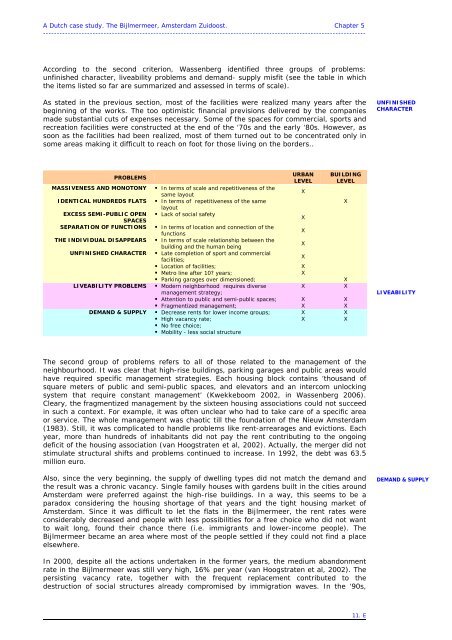

According to the second criterion, Wassenberg identified three groups <strong>of</strong> problems:<br />

unfinished character, liveability problems and demand- supply misfit (see the table in which<br />

the items listed so far are summarized and assessed in terms <strong>of</strong> scale).<br />

As stated in the previous section, most <strong>of</strong> the facilities were realized many years after the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> the works. The too optimistic financial previsions delivered by the companies<br />

made substantial cuts <strong>of</strong> expenses necessary. Some <strong>of</strong> the spaces <strong>for</strong> commercial, sports and<br />

recreation facilities were constructed at the end <strong>of</strong> the ‘70s and the early ‘80s. However, as<br />

soon as the facilities had been realized, most <strong>of</strong> them turned out to be concentrated only in<br />

some areas making it difficult to reach on foot <strong>for</strong> those living on the borders..<br />

PROBLEMS<br />

URBAN<br />

LEVEL<br />

BUILDING<br />

LEVEL<br />

MASSIVENESS AND MONOTONY In terms <strong>of</strong> scale and repetitiveness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

same layout<br />

X<br />

IDENTICAL HUNDREDS FLATS In terms <strong>of</strong> repetitiveness <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

layout<br />

X<br />

EXCESS SEMI-PUBLIC OPEN<br />

SPACES<br />

Lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>social</strong> safety<br />

X<br />

SEPARATION OF FUNCTIONS In terms <strong>of</strong> location and connection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

functions<br />

X<br />

THE INDIVIDUAL DISAPPEARS In terms <strong>of</strong> scale relationship between the<br />

building and the human being<br />

X<br />

UNFINISHED CHARACTER Late completion <strong>of</strong> sport and commercial<br />

facilities;<br />

X<br />

Location <strong>of</strong> facilities; X<br />

Metro line after 10? years; X<br />

Parking garages over dimensioned; X<br />

LIVEABILITY PROBLEMS Modern neighborhood requires diverse<br />

management strategy;<br />

X X<br />

Attention to public and semi-public spaces; X X<br />

Fragmentized management; X X<br />

DEMAND & SUPPLY Decrease rents <strong>for</strong> lower income groups; X X<br />

High vacancy rate;<br />

No free choice;<br />

Mobility - less <strong>social</strong> structure<br />

X X<br />

The second group <strong>of</strong> problems refers to all <strong>of</strong> those related to the management <strong>of</strong> the<br />

neighbourhood. It was clear that high-rise buildings, parking garages and public areas would<br />

have required specific management <strong>strategies</strong>. Each <strong>housing</strong> block contains ‘thousand <strong>of</strong><br />

square meters <strong>of</strong> public and semi-public spaces, and elevators and an intercom unlocking<br />

system that require constant management’ (Kwekkeboom 2002, in Wassenberg 2006).<br />

Cleary, the fragmentized management by the sixteen <strong>housing</strong> associations could not succeed<br />

in such a context. For example, it was <strong>of</strong>ten unclear who had to take care <strong>of</strong> a specific area<br />

or service. The whole management was chaotic till the foundation <strong>of</strong> the Nieuw Amsterdam<br />

(1983). Still, it was complicated to handle problems like rent-arrearages and evictions. Each<br />

year, more than hundreds <strong>of</strong> inhabitants did not pay the rent contributing to the ongoing<br />

deficit <strong>of</strong> the <strong>housing</strong> association (van Hoogstraten et al, 2002). Actually, the merger did not<br />

stimulate structural shifts and problems continued to increase. In 1992, the debt was 63.5<br />

million euro.<br />

Also, since the very beginning, the supply <strong>of</strong> dwelling types did not match the demand and<br />

the result was a chronic vacancy. Single family houses with gardens built in the cities around<br />

Amsterdam were preferred against the high-rise buildings. In a way, this seems to be a<br />

paradox considering the <strong>housing</strong> shortage <strong>of</strong> that years and the tight <strong>housing</strong> market <strong>of</strong><br />

Amsterdam. Since it was difficult to let the flats in the Bijlmermeer, the rent rates were<br />

considerably decreased and people with less possibilities <strong>for</strong> a free choice who did not want<br />

to wait long, found their chance there (i.e. immigrants and lower-income people). The<br />

Bijlmermeer became an area where most <strong>of</strong> the people settled if they could not find a place<br />

elsewhere.<br />

In 2000, despite all the actions undertaken in the <strong>for</strong>mer years, the medium abandonment<br />

rate in the Bijlmermeer was still very high, 16% per year (van Hoogstraten et al, 2002). The<br />

persisting vacancy rate, together with the frequent replacement contributed to the<br />

destruction <strong>of</strong> <strong>social</strong> structures already compromised by immigration waves. In the ‘90s,<br />

11. E<br />

UNFINISHED<br />

CHARACTER<br />

LIVEABILITY<br />

DEMAND & SUPPLY