Sustainable Building Technical Manual - Etn-presco.net

Sustainable Building Technical Manual - Etn-presco.net

Sustainable Building Technical Manual - Etn-presco.net

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

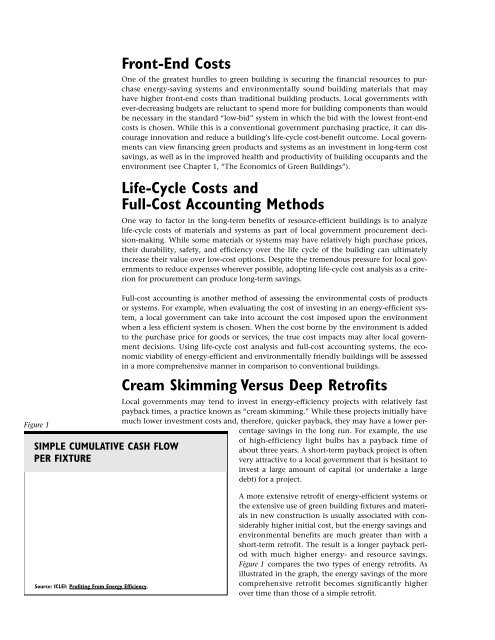

Figure 1Front-End CostsSIMPLE CUMULATIVE CASH FLOWPER FIXTUREOne of the greatest hurdles to green building is securing the financial resources to purchaseenergy-saving systems and environmentally sound building materials that mayhave higher front-end costs than traditional building products. Local governments withever-decreasing budgets are reluctant to spend more for building components than wouldbe necessary in the standard “low-bid” system in which the bid with the lowest front-endcosts is chosen. While this is a conventional government purchasing practice, it can discourageinnovation and reduce a building’s life-cycle cost-benefit outcome. Local governmentscan view financing green products and systems as an investment in long-term costsavings, as well as in the improved health and productivity of building occupants and theenvironment (see Chapter 1, “The Economics of Green <strong>Building</strong>s”).Life-Cycle Costs andFull-Cost Accounting MethodsOne way to factor in the long-term benefits of resource-efficient buildings is to analyzelife-cycle costs of materials and systems as part of local government procurement decision-making.While some materials or systems may have relatively high purchase prices,their durability, safety, and efficiency over the life cycle of the building can ultimatelyincrease their value over low-cost options. Despite the tremendous pressure for local governmentsto reduce expenses wherever possible, adopting life-cycle cost analysis as a criterionfor procurement can produce long-term savings.Full-cost accounting is another method of assessing the environmental costs of productsor systems. For example, when evaluating the cost of investing in an energy-efficient system,a local government can take into account the cost imposed upon the environmentwhen a less efficient system is chosen. When the cost borne by the environment is addedto the purchase price for goods or services, the true cost impacts may alter local governmentdecisions. Using life-cycle cost analysis and full-cost accounting systems, the economicviability of energy-efficient and environmentally friendly buildings will be assessedin a more comprehensive manner in comparison to conventional buildings.Cream Skimming Versus Deep RetrofitsLocal governments may tend to invest in energy-efficiency projects with relatively fastpayback times, a practice known as “cream skimming.” While these projects initially havemuch lower investment costs and, therefore, quicker payback, they may have a lower percentagesavings in the long run. For example, the useof high-efficiency light bulbs has a payback time ofabout three years. A short-term payback project is oftenvery attractive to a local government that is hesitant toinvest a large amount of capital (or undertake a largedebt) for a project.Source: ICLEI: Profiting From Energy Efficiency.A more extensive retrofit of energy-efficient systems orthe extensive use of green building fixtures and materialsin new construction is usually associated with considerablyhigher initial cost, but the energy savings andenvironmental benefits are much greater than with ashort-term retrofit. The result is a longer payback periodwith much higher energy- and resource savings.Figure 1 compares the two types of energy retrofits. Asillustrated in the graph, the energy savings of the morecomprehensive retrofit becomes significantly higherover time than those of a simple retrofit.