The SRA Symposium - College of Medicine

The SRA Symposium - College of Medicine

The SRA Symposium - College of Medicine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

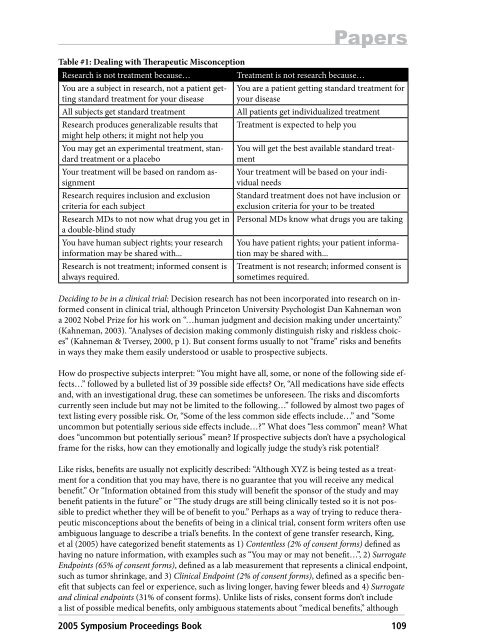

Table #1: Dealing with <strong>The</strong>rapeutic Misconception<br />

Research is not treatment because… Treatment is not research because…<br />

You are a subject in research, not a patient getting<br />

standard treatment for your disease<br />

You are a patient getting standard treatment for<br />

your disease<br />

All subjects get standard treatment All patients get individualized treatment<br />

Research produces generalizable results that<br />

might help others; it might not help you<br />

You may get an experimental treatment, standard<br />

treatment or a placebo<br />

Your treatment will be based on random assignment<br />

Research requires inclusion and exclusion<br />

criteria for each subject<br />

Research MDs to not now what drug you get in<br />

a double-blind study<br />

You have human subject rights; your research<br />

information may be shared with...<br />

Research is not treatment; informed consent is<br />

always required.<br />

Treatment is expected to help you<br />

Papers<br />

You will get the best available standard treatment<br />

Your treatment will be based on your individual<br />

needs<br />

Standard treatment does not have inclusion or<br />

exclusion criteria for your to be treated<br />

Personal MDs know what drugs you are taking<br />

You have patient rights; your patient information<br />

may be shared with...<br />

Treatment is not research; informed consent is<br />

sometimes required.<br />

Deciding to be in a clinical trial: Decision research has not been incorporated into research on informed<br />

consent in clinical trial, although Princeton University Psychologist Dan Kahneman won<br />

a 2002 Nobel Prize for his work on “…human judgment and decision making under uncertainty.”<br />

(Kahneman, 2003). “Analyses <strong>of</strong> decision making commonly distinguish risky and riskless choices”<br />

(Kahneman & Tversey, 2000, p 1). But consent forms usually to not “frame” risks and benefits<br />

in ways they make them easily understood or usable to prospective subjects.<br />

How do prospective subjects interpret: “You might have all, some, or none <strong>of</strong> the following side effects…”<br />

followed by a bulleted list <strong>of</strong> 39 possible side effects? Or, “All medications have side effects<br />

and, with an investigational drug, these can sometimes be unforeseen. <strong>The</strong> risks and discomforts<br />

currently seen include but may not be limited to the following…” followed by almost two pages <strong>of</strong><br />

text listing every possible risk. Or, “Some <strong>of</strong> the less common side effects include…” and “Some<br />

uncommon but potentially serious side effects include…?” What does “less common” mean? What<br />

does “uncommon but potentially serious” mean? If prospective subjects don’t have a psychological<br />

frame for the risks, how can they emotionally and logically judge the study’s risk potential?<br />

Like risks, benefits are usually not explicitly described: “Although XYZ is being tested as a treatment<br />

for a condition that you may have, there is no guarantee that you will receive any medical<br />

benefit.” Or “Information obtained from this study will benefit the sponsor <strong>of</strong> the study and may<br />

benefit patients in the future” or “<strong>The</strong> study drugs are still being clinically tested so it is not possible<br />

to predict whether they will be <strong>of</strong> benefit to you.” Perhaps as a way <strong>of</strong> trying to reduce therapeutic<br />

misconceptions about the benefits <strong>of</strong> being in a clinical trial, consent form writers <strong>of</strong>ten use<br />

ambiguous language to describe a trial’s benefits. In the context <strong>of</strong> gene transfer research, King,<br />

et al (2005) have categorized benefit statements as 1) Contentless (2% <strong>of</strong> consent forms) defined as<br />

having no nature information, with examples such as “You may or may not benefit…”, 2) Surrogate<br />

Endpoints (65% <strong>of</strong> consent forms), defined as a lab measurement that represents a clinical endpoint,<br />

such as tumor shrinkage, and 3) Clinical Endpoint (2% <strong>of</strong> consent forms), defined as a specific benefit<br />

that subjects can feel or experience, such as living longer, having fewer bleeds and 4) Surrogate<br />

and clinical endpoints (31% <strong>of</strong> consent forms). Unlike lists <strong>of</strong> risks, consent forms don’t include<br />

a list <strong>of</strong> possible medical benefits, only ambiguous statements about “medical benefits,” although<br />

2005 <strong>Symposium</strong> Proceedings Book 109