aistand south~ern afrkca - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

aistand south~ern afrkca - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

aistand south~ern afrkca - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

example, milk production fromindigeacus cattle<br />

was reported to range from 150 to 25 kg a year<br />

in Kenya (MLD, 1986; MLD, 1990), to average<br />

200 kg a year in Tanzania (Ministry of<br />

Agriculture, 1972) and to average 300 kg a<br />

lactation in Ethiopia (Grybeels and And-irson,<br />

1983). Research has also 2hown that ex'.ic<br />

breeds respond better to impiovements i.i the<br />

environmentthandindigenoujcattle(Trailand<br />

Gregory, 1981).<br />

These resu'ts thus indicate that it is possible<br />

for exotic dairy cattle to achieve their potential<br />

for milk production given aii upgraded<br />

environment in the threo production sectors.<br />

Beef cattle<br />

There seems to be no reported work relating to<br />

on-farm evaluation of beef breeds in the region.<br />

What information has been collated is on the<br />

performances of a given breed across production<br />

systems. Table 6 gives a summary comparing the<br />

performance of cattle between the traditional<br />

sector and the ranch network in Botswana. It is<br />

clear from the estimates Fiven in Table 6 that<br />

productivity is very low in the traditional cector<br />

because of low calving percentage and low<br />

weaning weight.<br />

Data from Malawi indicate that, in the<br />

Malawi Zebu, there is not much difference in age<br />

at first calving between animals in the<br />

traditional sector (3.3 years; de Koning, 1977)<br />

and those on research stations (3.2 years;<br />

Kasowanjete, 1977). The calving percentage also<br />

did not vary much between production systems<br />

(63.6 and 66.7%, respectively) (Koning, 1977;<br />

Department of Agriculture, 1972). However,<br />

there was a notable difference in the calving<br />

interval between animals in the traditional<br />

sector and those on the rcsearch station (2.4 and<br />

1.2 years, respectivly).<br />

In Tanzania age at first calving was estimated<br />

at four years, calving interval at 1.5 years and<br />

calf mortality at 27% in indigenous cattle (Mpiri,<br />

1990). Similarly, in Ethiopia cows did not calve<br />

until approximately four years of age (Gryseels<br />

and Anderson, 1983). Although there are<br />

variations between countries, in general the<br />

productivity of indigenous cattle in the<br />

traditional sector is lower than that ofexotic beef<br />

cattle and their crosses in the commerc:al sector.<br />

Impact of exotic cattle<br />

Based on results from research stations, and a<br />

few from farms, exotic cattle can perform better<br />

than indigenous cattle given ar improved<br />

environment. Policy makers and livestock<br />

administrateor have been aware of these<br />

advantges for a very long time. However, the<br />

question to be asked is what impact have exotic<br />

cattle made since their introduction by colonial<br />

farmers and by livestock policy makers?<br />

Beef cattle<br />

Since the introduction ofexotic beef cattle in the<br />

region they have in practical terms not spread<br />

from the large-scale commercial sector to other<br />

sectors in most countries, except in Botswana. In<br />

Botswana farmers in both the commercial and<br />

the traditional sector are implementing the<br />

recommendation to croesbred Tswana cws to<br />

Brahman blls for use under general conditions<br />

and to Simmental bulls (a dual-purpose breed)<br />

for use under conditions of improved management<br />

(as defined b I some degree of fencing<br />

for control of breeding herds, attention to disease<br />

and mineral supplements and adequate water<br />

supply at a reasonable distance). The wide<br />

spread use ofexotic breeds in Botswa-a has been<br />

made possible by the use ofa bull subsidy scheme<br />

and, most importantly, by the operation of an<br />

artificial insemination scheme for beef in the<br />

traditional sector.<br />

In terms of contribution to meat production,<br />

it seems that, in general, exotic beef cattle and<br />

their crosses have riot contributed much more<br />

than the indigenous cattle. For example, Za<strong>mb</strong>ia<br />

has 2.2 million head of cattle in traditional<br />

sector, almost all ofwiich are indigenous breeds,<br />

and 0.48 million heau ofcattle are in commercial<br />

sector, out of which 0.06 million head are dairy<br />

animals. The off-take rates are estimated at 6<br />

and 15% for traditional and commercial sector,<br />

respectively (Kaluba, 1992). Thus, although the<br />

off-take rate is very low in indigenous cattle, they<br />

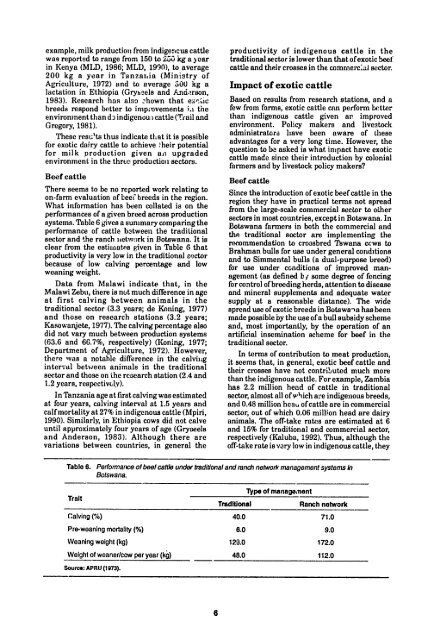

Table 6. Performance of beef cattle under traditional and ranch netwoikmanagementsystems in<br />

Botswana.<br />

Trait<br />

Type of management<br />

Traditional Ranch network<br />

Calving (%) 40.0 71.0<br />

Pro-weaning mortality (%) 6.0 9.0<br />

Weaning weight (kg) 129.0 172.0<br />

Weight of weaner/cow per year (kg) 48.0 112.0<br />

Source: APRU (1973).<br />

6