- Page 3: DEVELOPMENTS IN CERAMIC MATERIALS R

- Page 6 and 7: Copyright © 2007 by Nova Science P

- Page 9 and 10: PREFACE Ceramics are refractory, in

- Page 11 and 12: Preface ix crystals is discussed. A

- Page 13: Preface xi spectra and the directio

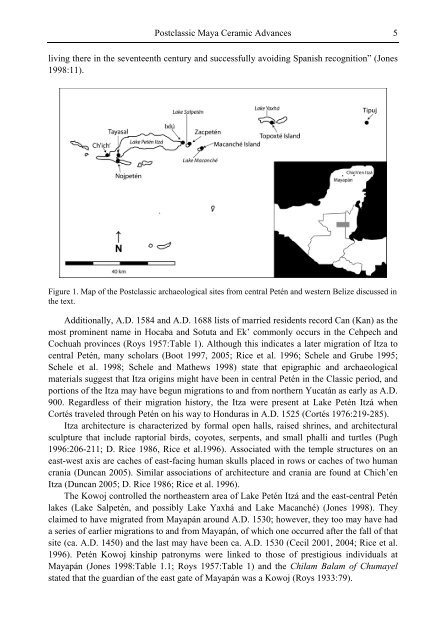

- Page 16 and 17: 2 Leslie G. Cecil comprehensive dat

- Page 20 and 21: 6 Leslie G. Cecil The main architec

- Page 22 and 23: 8 Leslie G. Cecil can study “the

- Page 24 and 25: 10 Leslie G. Cecil Middleton et al.

- Page 26 and 27: 12 Leslie G. Cecil The laser ablate

- Page 28 and 29: 14 Leslie G. Cecil There are two ge

- Page 30 and 31: 16 Leslie G. Cecil distinct recipes

- Page 32 and 33: 18 Leslie G. Cecil second group (Fi

- Page 34 and 35: 20 Leslie G. Cecil The Vitzil-Orang

- Page 36 and 37: 22 Leslie G. Cecil Table 3. Mahalan

- Page 38 and 39: 24 Leslie G. Cecil Ixlú and Ch’i

- Page 40 and 41: 26 Leslie G. Cecil structures (D. R

- Page 42 and 43: 28 Leslie G. Cecil paste and Macanc

- Page 44 and 45: 30 Leslie G. Cecil Bieber, A. M. Jr

- Page 46 and 47: 32 Leslie G. Cecil Kepecs, S. M., a

- Page 48 and 49: 34 Leslie G. Cecil Schele, L., Grub

- Page 50 and 51: 36 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 52 and 53: 38 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 54 and 55: 40 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 56 and 57: 42 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 58 and 59: 44 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 60 and 61: 46 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 62 and 63: 48 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 64 and 65: 50 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 66 and 67: 52 Z. C. Li, Z. J. Pei and C. Tread

- Page 68 and 69:

54 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 70 and 71:

56 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 72 and 73:

58 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 74 and 75:

60 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 76 and 77:

62 I, % 100 80 60 40 20 0 T. T. Bas

- Page 78 and 79:

64 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 80 and 81:

66 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 82 and 83:

68 Fluorescence, a.u. 1 T. T. Basie

- Page 84 and 85:

70 Fluorescence, a.u. 1 0.1 0.01 0.

- Page 86 and 87:

72 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 88 and 89:

74 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 90 and 91:

76 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 92 and 93:

78 k, cm -1 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4

- Page 94 and 95:

80 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 96 and 97:

82 Photon counts 300 250 200 150 10

- Page 98 and 99:

84 Fluorescence, a.u. I transfer ,

- Page 100 and 101:

86 ln(I transfer (t)) -4.2 -4.4 -4.

- Page 102 and 103:

88 Fluorescence, a.u. I transfer ,

- Page 104 and 105:

90 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 106 and 107:

92 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 108 and 109:

94 T. T. Basiev, V. A. Demidenko, K

- Page 111 and 112:

In: Developments in Ceramic Materia

- Page 113 and 114:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 115 and 116:

a c Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Ma

- Page 117 and 118:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 119 and 120:

Transmission Transmission Transmiss

- Page 121 and 122:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 123 and 124:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 125 and 126:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 127 and 128:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 129 and 130:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 131 and 132:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 133 and 134:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 135 and 136:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 137 and 138:

Sm (J/Kmol) Sm (J/Kmol) 15 10 5 Syn

- Page 139 and 140:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 141 and 142:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 143 and 144:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 145 and 146:

Intensity (a.u.) Intensity (a.u.) 8

- Page 147 and 148:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 149 and 150:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 151 and 152:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 153 and 154:

Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Magnet

- Page 155 and 156:

In: Developments in Ceramic Materia

- Page 157 and 158:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 159 and 160:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 161 and 162:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 163 and 164:

3.2. Wall-in Positions The Use of C

- Page 165 and 166:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 167 and 168:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 169 and 170:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 171 and 172:

IACC ( τ ) = t2 ∫ The Use of Cer

- Page 173 and 174:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 175 and 176:

where σ res is the scattering cros

- Page 177 and 178:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 179 and 180:

D50 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 The Use

- Page 181 and 182:

Definition (D50) 1 0.95 0.9 0.85 0.

- Page 183 and 184:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 185 and 186:

The Use of Ceramic Pots in Old Wors

- Page 187 and 188:

In: Developments in Ceramic Materia

- Page 189 and 190:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 191 and 192:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 193 and 194:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 195 and 196:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 197 and 198:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 199 and 200:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 201 and 202:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 203 and 204:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 205 and 206:

q x = Modeling of Thermal Transport

- Page 207 and 208:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 209 and 210:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 211 and 212:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 213 and 214:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 215 and 216:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 217 and 218:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 219 and 220:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 221 and 222:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 223:

Modeling of Thermal Transport in Ce

- Page 226 and 227:

212 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 228 and 229:

214 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 230 and 231:

216 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 232 and 233:

218 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 234 and 235:

220 ε S 33 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron

- Page 236 and 237:

222 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 238 and 239:

224 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 240 and 241:

226 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 242 and 243:

228 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 244 and 245:

230 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 246 and 247:

232 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 248 and 249:

234 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 250 and 251:

236 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 252 and 253:

238 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 254 and 255:

240 R. Ramesh, H. Kara, Ron Stevens

- Page 256 and 257:

242 Development of Display Technolo

- Page 258 and 259:

244 Li Chen technology moved to the

- Page 260 and 261:

246 Li Chen The continuing evolutio

- Page 262 and 263:

248 Li Chen the back contact cathod

- Page 264 and 265:

250 Li Chen Figure 3. Vertical side

- Page 266 and 267:

252 Li Chen Figure 6. Molybdenum mi

- Page 268 and 269:

254 Li Chen Figure 8(a). I-V curve

- Page 270 and 271:

256 Li Chen Figure 9. Life time tes

- Page 272 and 273:

258 Figure 11(a). Plasma generated

- Page 274 and 275:

260 Li Chen [13] C.A. Spindt, K.R.

- Page 276 and 277:

262 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 278 and 279:

264 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 280 and 281:

266 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 282 and 283:

268 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 284 and 285:

270 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 286 and 287:

272 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 288 and 289:

274 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 290 and 291:

276 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 292 and 293:

278 S. Ardizzone, C. L. Bianchi, G.

- Page 295 and 296:

A absorption spectra, 66, 67, 77, 7

- Page 297 and 298:

correlation function, 156 corrosion

- Page 299 and 300:

group membership, 13, 20, 21, 22, 2

- Page 301 and 302:

microstructure(s), x, xi, 73, 74, 2

- Page 303 and 304:

efraction index, 61 refractive inde

- Page 305 and 306:

time, vii, ix, 1, 3, 7, 8, 11, 26,